Why Do Some People Think the Human Soul Weighs 21 Grams?

It’s often said that it’s impossible to put a price on a human life, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t define it by other metrics, something physician Duncan MacDougall tried to do in the early 20th century by setting up an experiment to discern the weight of a single human soul. His answer? A mere 21 grams. So how did he come to this figure and is there any validity to his study? Do people really suddenly lose about 21 grams of weight upon death?

It’s often said that it’s impossible to put a price on a human life, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you can’t define it by other metrics, something physician Duncan MacDougall tried to do in the early 20th century by setting up an experiment to discern the weight of a single human soul. His answer? A mere 21 grams. So how did he come to this figure and is there any validity to his study? Do people really suddenly lose about 21 grams of weight upon death?

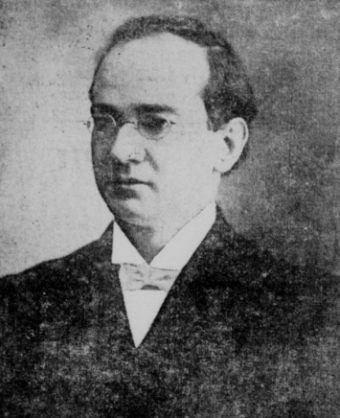

As to the man himself, Duncan MacDougall’s life before his famed experiment has largely been lost to history, other than that he was born sometime in 1866. As for the experiment, this occurred sometime in 1901 while he was a physician working in Haverhill, Massachusetts. A 1907 article covering his study by The New York Times notes that MacDougall was the “head of a research society” at the time and that he was “reputable”, but fails to give any further details on his background.

The only other thing we really know for sure is that MacDougall was a religious man, though, again, we have no real idea what particular religious ideology he ascribed to, only that he postulated that dogs do not have souls, something we’ll come back to later.

MacDougall was apparently obsessed with the idea that the human soul, if it indeed did exist, would have some kind of quantifiable mass that could be measured. To quote the man himself:

We are therefore driven back upon the assumption that the soul substance so necessary to the conception of continuing personal identity, after the death of this material body, must still be a form of gravitative matter, or perhaps a middle form of substance neither gravitative matter or ether, not capable of being weighed, and yet not identical with ether. Since however the substance considered in our hypothesis is linked organically with the body until death takes place, it appears to me more reasonable to think that it must be some form of gravitative matter, and therefore capable of being detected at death by weighing a human being in the act of death.

Towards this end, MacDougall sought to measure the weight of the soul by placing people dying of terminal illnesses upon a specially constructed set of scales designed like a bed.

MacDougall reported in his findings that the scales constructed for the experiment were accurate to within “2 tenths of an ounce” (about 5 grams). As for his subjects, he sought out patients dying of tuberculosis because, “It seemed to me best to select a patient dying with a disease that produces great exhaustion, the death occurring with little or no muscular movement, because in such a case, the beam could be kept more perfectly at balance and any loss occurring readily noted.”

In the end, MacDougall was able to find six suitable patients for his study, but only four ended up being useful, all of whom were men. As for the other two, one was a woman in a diabetic coma and the other a man with an undisclosed illness. However, neither result could be counted as the woman died before accurate measurements could be taken due to, to quote him, “interference by people opposed to our work”. As for the man, he died within 5 minutes of being put on the scales, which wasn’t enough time for MacDougall to balance everything.

So what about the other four patients? Well, MacDougall carefully observed each one, meticulously noting every drop in weight from perspiration and respiratory moisture over time so as to properly account for this as he waited for them to die. And, if you’re wondering as a sort of follow up to our article Do People Really Defecate Directly After Death and, If So, How Often Does It Occur?, some of the patients urinated and/or defecated in their final moments, which MacDougall left so as not to throw off his measurements.

After accounting for the loss of weight due to evaporation, MacDougall and his team found that at the apparent moment of death, the first patient suddenly lost about ¾ of an ounce (21.3 grams) that couldn’t be accounted for by anything he could think of. To quote his paper on the subject,

This loss of weight could not be due to evaporation of respiratory moisture and sweat, because that had already been determined to go on, in his case, at the rate of one sixtieth of an ounce per minute, whereas this loss was sudden and large, three-fourths of an ounce in a few seconds.

The bowels did not move; if they had moved the weight would still have remained upon the bed except for a slow loss by the evaporation of moisture depending, of course, upon the fluidity of the feces. The bladder evacuated one or two drams of urine. This remained upon the bed and could only have influenced the weight by slow gradual evaporation and therefore in no way could account for the sudden loss.

There remained but one more channel of loss to explore, the expiration of all but the residual air in the lungs. Getting upon the bed myself, my colleague put the beam at actual balance. Inspiration and expiration of air as forcibly as possible by me had no effect upon the beam. My colleague got upon the bed and I placed the beam at balance. Forcible inspiration and expiration of air on his part had no effect. In this case we certainly have an inexplicable loss of weight of three-fourths of an ounce. Is it the soul substance? How other shall we explain it?

The other three patients exhibited a similar loss of weight, but one patient put the weight back on somehow and the other two randomly lost weight again a few minutes later. The good doctor noted, however, that in these cases it was much more difficult to determine exactly when the people expired than in the first case. For example, with subject two, he states,

The last fifteen minutes he had ceased to breathe but his facial muscles still moved convulsively, and then, coinciding with the last movement of the facial muscles, the beam dropped… This patient was of a totally different temperament from the first, his death was very gradual, so that we had great doubts from the ordinary evidence to say just what moment he died.

Nevertheless, now convinced he’d demonstrated that the human soul has weight, he moved on to test and see if dogs had souls, which he suspected not. Specifically, MacDougall tested this hypothesis by repeating the experiment on 15 dogs and noted that no similar drop in weight occurred at the instant of doggy death.

Sadly, Dr MacDougall states, “The ideal tests on dogs would be obtained in those dying from some disease that rendered them much exhausted and incapable of struggle. It was not my fortune to get dogs dying from such sickness.” Thus, to get the desired result, he used drugs to make sure the dogs laid still and ultimately died.

He went on to publish the results of his experiments in the April of 1907 edition of American Medicine in a paper titled Hypothesis Concerning Soul Substance Together

with Experimental Evidence of The Existence of Such Substance.

Around the same time, the New York Times got wind of MacDougall’s experiments and reported on them as well. The story was global news and, even today, people continue to cite MacDougall’s experiment as definitive proof of the existence of the soul, popularly quoting his ¾ of an ounce figure as 21 grams.

Much as with scientists today who almost always see their studies inaccurately represented as far more definitive than they actually are in media and in public consciousness, MacDougall had this happen too. This was despite that in his paper he explicitly stated “I am aware that a large number of experiments would require to be made before the matter can be proved beyond any possibility of error.”

This, of course, is a sentiment echoed by countless scientists in the century since MacDougall published his findings. In the end, while the weight variance over time in the four human subjects is fascinating, regardless of whether one is considering souls, his study was far too limited to draw any clear conclusions from.

In addition, experts have criticised the accuracy of the equipment MacDougall used, as well as the fact that only one patient gave marked results, with the others having additional weight variances that couldn’t be explained by the soul hypothesis, unless they had multiple souls coming and going. Yet MacDougall casually dismissed that variance and made the overall results fit his hypothesis.

There’s also the inherent difficulty of determining the “exact” moment of death. As, in truth, the death of the body is a long drawn out process. Some who believe humans have souls have also raised the question of how exactly one knows when a soul leaves the body in the first place? After all, plenty of people have been declared clinically dead even with advanced, modern medical equipment, only to be revived later, in certain hypothermic cases sometimes a long while later, leading to the common expression among medical professionals, “Not dead until warm and dead.”

And even in more normal cases, as our resident paramedic author noted in his fantastic article How Long a Person’s Heart Has To Be Stopped Before Medics Wouldn’t Try to Revive Them, “I can tell you that the longest I have ever personally seen a person’s heart not beating and they were able to be successfully revived (meaning they walked out of the hospital with somewhat normal neurological function) was over 40 minutes.” For more on all that, check out the preceding link.

So, in these cases does the soul leave and then come back? Or does it stick around to see how things will work out?

As for MacDougall, he defined the moment of death, or more aptly the moment when the soul would leave the body as being “virtually at the instant of the last breath, though in persons of sluggish temperament, it may remain in the body for a full minute.”

As you might imagine, MacDougall’s experiments on humans have never been repeated for ethical reasons, though it is interesting that pretty much every other thing is monitored and tabulated when a person dies, so we suppose if hospitals simply started making hospital beds accurate scales too, nobody would much mind in that case. But nobody has yet done that.

That said, others have attempted the same type of experiments on various animals with mixed results. In one study with mice, the results of MacDougall’s dog experiments were confirmed- apparently mice don’t have souls either. Curiously, in at least one experiment published in the Journal of Scientific Exploration in 2001, Unexplained Weight Gain Transients at the Moment of Death, it was found that seven adult sheep involved actually saw an inexplicable rise in body weight for a brief period of 1-6 seconds directly after their hearts stopped, before the weight would once again return to normal. This did not occur in the lambs used in the study, nor the goat. What might have caused this is presently unknown, but it was fascinatingly consistent across all seven adult sheep.

Going back to MacDougall’s experiment, as to what caused the clear drop around the time the subject in question died, this isn’t clear, though as noted by the random weight fluctuations on the other subjects, seemingly at random times, most point to simply that his equipment wasn’t as precise as MacDougall thought and was perhaps just prone to variance at the slightest provocation, such as if the individual in question had moved slightly upon death.

As for MacDougall, he never attempted to replicate the experiment, instead turning his attention to trying to find a way to photograph the soul at the moment of death using X-rays. These experiments, if they ever occurred, apparently never went anywhere as he never published any findings. As for the man himself, he lost his own 21 grams in 1920 at the age of 54 without making any further progress or impact on the scientific world.

Nonetheless, the results of his experiment live on and there are still many people today who believe the soul has a mass of 21 grams because of it. Something we’re guessing they’d not be as keen to cite if they also knew the same experiment apparently also conclusively proved doggy heaven doesn’t exist.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- That Time Someone Actually Achieved the Alchemists’ Dream of Turning a Different Material Into Gold

- What Happens When a Town Votes For a Dog or Cat to Be Mayor?

- Two-Headed Dogs and Human Head Transplants

- That Time Five Guys Volunteered to Stand at Ground Zero of a Nuclear Blast Just to See What Would Happen

- Who Started the Moon Landing Hoax Conspiracy Theory?

Bonus Fact:

If we were actually able to convert matter perfectly to energy, with 1 kg of matter being completely annihilated, the energy produced from just that small amount of matter is equivalent to about 42.95 mega tons of TNT. So, an adult male weighing in at around 200 pounds (about 90 kg or, just for fun- 14.2 stones) has somewhere in the vicinity of 4000 megatons of TNT potential in their matter if completely annihilated.

This is about 80 times more energy than was produced by the largest ever detonated nuclear bomb, the Tzar Bomba, which itself produced a blast about 1,400 times more powerful than the combined explosions of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

To further illustrate, 1 megaton of TNT, when converted to kilowatt hours, makes enough electricity to power an average American home for about 100,000 years. It is also enough to power the entire United States for a little over 3 days. So, 1 kg of some matter being completely annihilated would be able to power the entire United States for about four months. One average adult male then, when completely annihilated, would produce enough energy to power the U.S. for about 30 years if fully utilized.

On a completely baffling scale, a typical supernova explosion will give off the equivalent of about 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 megatons of TNT.

Expand for References| Share the Knowledge! |

|