Under the Lights: The First Baseball Game Played at Night

On a field about fifty miles from Boston, Strawberry Hill, on the evening of September 3, 1880, history was made. It is unlikely the department store employees who were tossing around a ball knew that this game would still be talked about 135 years later. As the crowd took their seats, the ball players took their positions; the Sun dipped below the horizon and the Moon rose. And then, the lights came on to illuminate the field. It was said the lights were as bright as “90,000 candles” burning simultaneously. This was the first baseball game played at night under artificial light. Here’s the story of that game and the history of baseball under the lights.

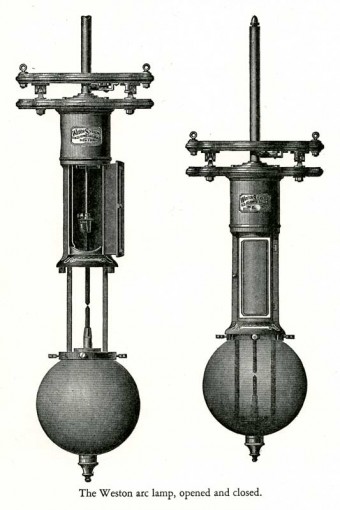

While it is commonly said that the the great New Jersey inventor Thomas Edison gave the world its first commercially produced electrical lights, that is false. While Edison did produce the first commercially viable light bulb, there were other companies that were trying to compete in the industry at the same time using various forms of electrical lighting. One of them was Boston’s Northern Electric Light Company, using electric arc lamps and Weston equipment.

Englishmen Edward Weston was a master electrician who began working with dynamos (electrical generators that produced direct current power through the use of commutators) in the 1870s. In 1875, Weston patented “rational construction of the dynamo,” that allowed him to “increase its efficiency from 45 percent to more than 90 percent.” When he premiered electric lamps using dynamo power at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, attention was scarce. But that didn’t deter him and he moved to the US permanently in 1877 to set up his own workshop in Newark, New Jersey, only about twenty miles from Edison’s lab in Menlo Park. Also a master marketer, he began putting up his electric arc lamps around Newark, most prominently on Newark Fire Department’s watchtower right in the center of town. This led to an influx of orders for his lamps, including for the city’s Military Park in 1878 and Boston’s Forest Garden in 1879.

Englishmen Edward Weston was a master electrician who began working with dynamos (electrical generators that produced direct current power through the use of commutators) in the 1870s. In 1875, Weston patented “rational construction of the dynamo,” that allowed him to “increase its efficiency from 45 percent to more than 90 percent.” When he premiered electric lamps using dynamo power at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, attention was scarce. But that didn’t deter him and he moved to the US permanently in 1877 to set up his own workshop in Newark, New Jersey, only about twenty miles from Edison’s lab in Menlo Park. Also a master marketer, he began putting up his electric arc lamps around Newark, most prominently on Newark Fire Department’s watchtower right in the center of town. This led to an influx of orders for his lamps, including for the city’s Military Park in 1878 and Boston’s Forest Garden in 1879.

Now, it isn’t entirely clear if Weston Electric Light Company collaborated with the Northern Electric Light Company or they were branches of the same company, but either way, the companies excelled at marketing and publicity and this September ball game was a perfect way to show off what Weston equipment could do.

The game was between well-known Boston department stores (as was the case back then, most “professional” teams were made up of employees who the company recruited and sometimes paid to win games as bragging rights) owned by Jordan Marsh and R.H. White. Jordan Marsh & Company was regionally famous for its wide variety of wares and blueberry muffins. R.H. White Company was Marsh’s biggest competitor with a giant store downtown. They were to play for a “purse of $50” (about $1,300 today) provided by the electric company.

During the day of September 3rd, the Northern Electric Light Company set up three wooden towers overlooking the field on Strawberry Hill, which laid on the shores Nantasket Beach in Hull, Massachusetts. According to the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), the towers were erected five hundred feet apart from one another in a “equilateral triangle.” Each was one hundred feet high with one row of 12 electrical lights, as described by the Boston Herald, “of the Weston patent.”

As advertised by the company, each light was supposed to match the light power of 2,500 candles. So, with three towers, 12 lights each, there was supposed to be the light of 90,000 candles in this limited area. Dynamos stored in a small shed were used to generate a “motive-power of 36 horses.” (See: Why Engines are Commonly Measured in Horsepower) As the Boston Herald noted, the Electric Light Company wanted to show off what they could do and hopefully attract bigger, better clients by creating “a model of the plan contemplated for lighting cities from overhead in vast areas, the estimate being that four towers to a square mile of area, each mounting lights aggregating 90,000 candle power, will suffice to flood the territory about with a light almost equal to midday.”

However, at the last moment, the department stores decide to forbid their employees from playing in the game. The reason is not known, but the players showed up anyway and played “sub rosa,” meaning in Latin “under the rose” or in secrecy, hence why all the accounts of the game do not mention players’ names or descriptions. If the players had been found out, there would be a chance they would no longer have a job. As recounted by the Official Scorer of the game thirty years after the fact, “inexpedient [for him] to mention any names of players, as some of them may still be employed in these establishments, although a number of players were recruited from the various jobbing houses in the dry-goods trade.”

It is not known how many fans exactly came out to the game. One account says about three hundred. Another account, noted with reporters added in, the number got closer to five hundred. Either way, it was pretty clear the fans came out not for the baseball, but for the light spectacle. In terms of the publicity, the game was a hit. But in practice and the quality of the game, not so much.

Complaints from reporters who attended the game appeared in the next day’s newspapers, centering around the amount of light. Said the Herald, “on account of the uncertain light, (resembling that of the moon at its full,) the batting was weak and the pitchers were poorly supported.” Baseball writer Preston Orem concluded that, “The light was quite imperfect and there were lots of errors made. The players had to bat and throw with caution. For the spectators the game had little interest as only the movements of the pitcher, in general, could be discerned, while the course of the ball eluded the vision of the watchers. … None of the reporters believed the idea to be at all practical.”

The game was tied 16 to 16 after nine innings, but the two teams agreed to call it, perhaps out of fear that the enveloping darkness would bring with it a line drive off the head. Additionally, it was noted that the players didn’t want to miss the last ferry to Boston, which was around 10 PM. For their efforts, the electric company rewarded the players and officials of the game with a generous supper (presumably back in Boston).

For the next fifty years, there would be sporadic night baseball games using artificial lights. In 1883, a game was played in Fort Wayne, Indiana in front of a couple thousand fans. A few more happened, but all were considered little more than a novelty. Into the 20th century, as electric lights became more mainstream, minor league baseball teams began hosting a night game or two per year. But it wouldn’t be until May 24, 1935 when Major League Baseball had its first night game under the lights between the Philadelphia Phillies and the Cincinnati Reds at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field. The home team won 2-1, but Clark Griffith, the owner of the Washington Senators, was skeptical. Saying to a newspaper, “There is no chance of night baseball ever being popular in the bigger cities. People there are educated to see the best there is and will stand for only the best. High-class baseball cannot be played at night under artificial light.”

Today, over eighty percent of Major League Baseball games are played at night, under the lights.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Abner Doubleday Did Not Invent Baseball

- There Once was a Little Person Who Played in Major League Baseball

- The Longest Game by Innings in Major League Baseball History

- How Baseball Groundskeepers Achieve Checkerboard Patterns in the Ballpark Grass

- That Time After Facing One Batter, Babe Ruth Punched an Umpire for Throwing Him Out of the Game, then Ruth’s Replacement Threw a No-Hitter

- Let There Be Light By Robert B. Payne,

- A handy book of curious information : comprising strange happenings in the life of men and animals, odd statistics, extraordinary phenomena and out of the way facts concerning the wonderlands of the earth

- The RH White Company…another giant of old Washington Street! – Shopping Days in Retro Boston

- Jordan Marsh – Wikipedia

- Night Baseball Comes to the Majors – Crowleyfield.net

- Nantasket Bay – Project Baseball Park

- “Under the Lights” By Oscar Eddleton – Society of Baseball Research

- May 24, 1935: MLB holds first night game – History.com

- September 2, 1880: Night baseball at Nantasket Beach by Craig B. Waff. – Society of Baseball Research

- Weston, the company – Westonmeter.org

- The Electrical Review, Volume 18 – Weston dyanmos

- Edward Weston: A Dynamic Electrical Engineer – Electronic Design

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

One comment