The Story Behind the Miranda Warning

In 1966, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Miranda v. Arizona, made it clear that the Constitution requires the police to warn criminal suspects in custody that they have the right to remain silent, that anything they say may be used against them, and that they have the right to an attorney – even if they can’t afford it. This warning, routinely given by local, state and federal law enforcement, as well as those who portray them in shows and movies, is today known simply as Miranda. But who was Miranda and what did he do?

In 1966, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case, Miranda v. Arizona, made it clear that the Constitution requires the police to warn criminal suspects in custody that they have the right to remain silent, that anything they say may be used against them, and that they have the right to an attorney – even if they can’t afford it. This warning, routinely given by local, state and federal law enforcement, as well as those who portray them in shows and movies, is today known simply as Miranda. But who was Miranda and what did he do?

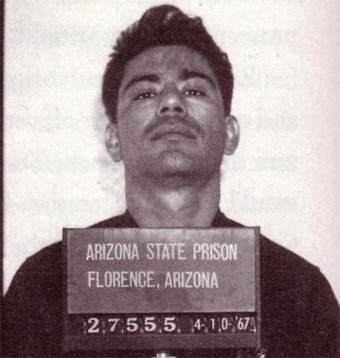

Born March 9, 1941 in Columbus, Arizona (or sometime in 1940 in Mesa, Arizona), it appears Ernesto Miranda had a very troubled childhood. Although few official records exist to support a biography on Miranda with the accuracy level we normally strive for here, a handful of otherwise reputable sources do offer some details purporting to be of his early life, which we’ll use to try to piece together a very brief biography of the man before his more well documented exploits which led to the “Miranda warning.”

Miranda’s mother apparently died when he was very young (around age 6), and he didn’t get along with the rest of his family. By the time he was in the eighth grade, he already had a criminal conviction for what appears to have been a felony burglary. One year later, after another burglary conviction, he was sentenced to reform school. Shortly after he was released, he was convicted of attempted rape and assault, and again returned to reform school.

After serving a two-year sentence, now 17, Miranda moved to Los Angeles where he seems to have been charged and held on suspicion of armed robbery and sexual offenses (purportedly being a “peeping Tom.”) After he turned 18, he returned to Arizona, where he enlisted in the Army.

After 15 months of service, Miranda was dishonorably discharged; during his tenure, Ernesto apparently spent time in the stockade for being repeatedly absent without leave (AWOL) and, again, doing his fair share of peeping. The Army then ordered him to have psychiatric counseling, but he reportedly only attended one session.

After his dishonorable discharge, Miranda slowly made his way back to Arizona, and, true to his modus operandi up to this point, spent time in a jail in Texas for vagrancy and in federal prison in Chillicothe, Ohio, and Lompoc, California for stealing a car and taking it across state lines.

In 1963, Miranda moved with his common-law wife and daughter to Mesa, Arizona, where he seemingly tried to go straight, taking a job at a loading dock in Phoenix.

This all brings us to the the much better documented part of Miranda’s life and the series of events that led to him being remembered today.

On March 3, 1963, an 18-year-old girl had just left work at a movie theater in downtown Phoenix and was walking home. It was then that she was approached by her kidnapper, who held a knife to her throat, told her not to scream, held her hands behind her back, put her in the back seat of a car and tied her up. Rather than call out or otherwise attempt to escape, she did what many would have done with a knife to their throat, reportedly freezing, feeling “she did not have time to do anything.”[1]

She was driven around for approximately 20 minutes, after which her assailant untied her and removed her clothes, although she tried to push him away, and asked him “Please don’t” and “Please let me go.” [2] In Miranda’s later confession, he claimed she didn’t resist, although he also said she had never “had any relations with a man before.”[3] According to the girl and the confession, Miranda then raped her.

At some point, the victim was freed and she went home and reported the incident to her family, and then the police. On March 13, 1963, Miranda was picked up and put in a line up, where the victim identified him.[4]

Miranda was taken to “Interrogation Room No. 2” and questioned by two officers. Two hours later, “the officers emerged from the interrogation room with a written confession signed by Miranda.” At the top of the confession, much of which was handwritten, was a typed statement that said in pertinent part:

I, Ernest A. Miranda, do hereby swear that I make this statement voluntarily and of my own free will, with no threats, coercion, or promises of immunity, and with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make may be used against me.[5]

According to one of the arresting officers, this portion was read to Miranda, apparently prior to his signing the statement, but after he had already confessed orally.[6]

Miranda was eventually convicted of kidnapping and rape (as well as a separate robbery charge) largely due to the introduction of his signed confession; he was sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison. He appealed and challenged the introduction of his confession, which he claimed violated the constitution “because the Supreme Court of the United States says the man is entitled to an attorney at the time of his arrest.”[7]

The Arizona Supreme Court upheld the conviction, in large part due to the fact that Miranda never asked for an attorney during his interrogation.[8]

On appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, Miranda’s conviction, as well as those of three others, was held to be unconstitutional; regarding Miranda, the court found that:

It is clear that Miranda was not in any way apprised of his right to consult with an attorney and to have one present during interrogation, nor was his right not to be compelled to incriminate himself effectively protected in any other manner. Without these warnings the statements were inadmissible. The mere fact that he signed a statement which contained a typed-in clause stating that he had full knowledge of his legal rights does not approach the knowing and intelligent waiver required to relinquish constitutional rights.[9]

The Miranda decision was not all that popular, and in fact, the vote among the Justices was only 5 to 4 in favor. Members of Congress were stirred to action, and in 1968, it passed the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets act that effectively trumped the Court’s Miranda requirement; however, the statute itself was essentially ignored by law enforcement, which by that time had already made the Miranda warning commonplace.

As for Miranda, although the conviction was overturned, he wasn’t in the clear. A subsequent trial was held in 1966 at which Miranda’s common-law wife testified for the prosecution that he had confessed to her. The jury returned a guilty verdict, and Miranda was again sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison.

Miranda was paroled in 1972. He violated his parole and was sent back to prison but was released, again, in 1975. On January 31, 1976, he was stabbed to death in what was apparently a bar fight.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- You Should Know About Jury Nullification

- Are You Really Entitled to a Phone Call When Arrested?

- What are Blue Laws?

- The Truth About Double Jeopardy

- Why Is It Illegal to Remove Your Mattress and Pillow Tags?

Bonus Facts:

- Over the years, subsequent Supreme Court decisions have chipped away at some of the seemingly absolute language in the Miranda decision. For example, in 1971, the Court held that while a confession given in violation of Miranda rights could not be used in the case in chief, it could be used to impeach (attack the credibility) of a defendant’s testimony. In 1980, the Court held that although a defendant had requested an attorney be present, his spontaneous statement to officers, who were not questioning him at the time, was not made during an “interrogation,” and as such, was admissible. Nonetheless, in 2000, the 1968 law purporting to overrule Miranda was taken up by the Court, which, by a 7-2 vote, decided to keep Miranda‘s warning requirements as: “Miranda has become embedded in routine police practice to the point where the warnings have become part of our national culture.“

- As the Miranda warning states, you are perfectly within your rights to keep your mouth shut when being interrogated by police, but Hollywood doesn’t actually tend to get this quite correct in the way they commonly portray it. The police only need to give you the Miranda warning if they are conducting a custodial interrogation (meaning you are not free to leave during the interrogation) and want the record of that interrogation to be admissible in court. Other than that, giving you the Miranda warning isn’t necessary. So, bottom line, contrary to what Hollywood shows, don’t expect them to give you the Miranda warning while they are cuffing you, and certainly don’t think you now have a get out of jail free card because they didn’t.

- You might be wondering why the Miranda warning is thought by many to be so essential, when it would seem to only protect the guilty who are unaware of their rights. (Note: the Miranda warning does not give you these rights; the Constitution does. The Miranda warning just makes sure you know your Constitutional rights when it comes to police interrogations.) The truth is, however, that these rights also greatly benefit the innocent as well, as you’ll soon see. To begin with, as we’ve previously stated, any lawyer worth anything will tell you to exercise the right to shut up, no matter if you are 100%, without a shadow of a doubt perfectly innocent and plan on being completely honest about it. Even if you are 100% innocent, there is literally no benefit for you to talk to the police in this situation where you find yourself detained and brought in for questioning about something you allegedly did. The police may even imply they’ll cut a deal with you or let you go, a la Hollywood depictions, if you talk and in some way incriminate yourself. They certainly won’t let you go if you incriminate yourself in any way and they also don’t make deals. That’s not their job, but rather the Prosecutor’s. Their job is to gather evidence against you. For more on this subject, check out this phenomenal lecture from Law Professor James Duane and Officer George Bruch of the Virginia Beach Police Department. Both agree: don’t talk to police. Ever. Officer Bruch even goes into some incredibly clever interrogation methods, or as the police refer to it “interview methods,” used to get people to talk. For instance, Officer Bruch often uses a tape recorder and, if getting nowhere in the interview, then pauses it and says what is said now is off the record. Of course, in that situation nothing is off the record and interview rooms have microphones and video cameras. (And they don’t even need those recordings anyway.) The tape recorder on the desk is just a prop. As you might have inferred from this, they are allowed to lie to you in any way they want to try to get you to talk. Needless to say, in these interrogations, the police are extreme experts at extracting information that might incriminate you and you are in a high stress situation. You will lose, no matter how clever, or even sometimes innocent, you are. And this is why the Miranda warning and the rights it talks about are important for the innocent too. If innocent, you might make it seem you’re guilty unintentionally due to the stress of the situation, perhaps even by trying to be clever or make jokes. You might also try to go along with whatever the officer is saying because they often dangle the carrot of “letting you go” if you do admit to something; as Officer Bruch stated, at that moment, you want nothing more than to be able to leave, regardless of your guilt or innocence. Or you might go along with them just to demonstrate respect and show how cooperative you are. In the process, you might accidentally lie to the officer or admit to a crime you didn’t commit. Neither case will work in your favor and this sort of thing isn’t as uncommon as you might think. The police are absolutely NOT looking to get an innocent person convicted, but they don’t know you and if you’re in that situation, they very likely don’t think you’re innocent to begin with (else they wouldn’t have detained you) and are looking for even the smallest hint of evidence to use to further their case against you. Another reason it is always better to work with a lawyer in these situations is, as Officer Bruch said in the previously linked lecture, “Everybody does something that they could get in trouble for… Don’t think you’re so innocent.”

- The Court Should Have Remained Silent

- Ernesto Miranda

- Ernesto Miranda

- Ernesto A. Miranda

- Facts and Case Summary

- Harris v. New York, 401 U.S. 222 (1971)

- History of Miranda Warning

- Miranda v. Arizona

- The Miranda Decision 40 Years Later

- The Miranda Rights Are Established

- “Miranda Slain” New York Times (1/31/76)

- Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 86 S.Ct. 1602, 16 L.Ed.2d 694 (1966)

- Rhode Island v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291 (1980)

- State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d 721 (Ariz. 1965)

- You Have the Right to Remain Silent

References

[1] State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d at 722-723.

[2] State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d at 723, 725

[3] State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d at 726.

[4] State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d at 723.

[5] State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d at 727

[6] Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. at 491-492.

[7] State v. Miranda, 401 P.2d at 729

[8] Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. at 492.

[9] Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. at 492

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

One quick correction. The Bill of Rights portion of the Constitution does not grant any rights whatsoever. The rights discussed in the first 10 amendments only discuss natural rights that any human being should expect their government to protect. Thus everyone has a natural right to not incriminate themselves, to not be tortured to confess to crimes, to not have their personal papers taken and examined without judicial warrant, etc. Any privilege granted in any of the later amendments (I’m thinking voting age specifically) is just that, a privilege granted that can be taken away. Rights are inherent in people, or inalienable, and not granted by government.

@RCCJr: Is that your opinion or is there some historical record that that is what the authors of the Bill of Rights meant?

They may be philosophically “natural rights”, similar to the ideas of John Locke, but the Bill of Rights DO also grand legal rights to us as well. Without that piece of paper stating that you are granted these “natural rights” by the US government, you would have a difficult time exercising these rights.

Absolutely correct, RCCjr. The Constitution SECURES our rights, it doesn’t not grant them. A government cannot grant a right. If it could, then a government could grant a right to kill, or steal and we’d have no recourse but to look the other way.

Emmett: “We are endowed by our Creator with inalienable rights…”

A professor told me that Miranda used to brag and pass out business cards with the Miranda Rights printed on them. When he was stabbed, the cop who was arresting the killer took one of these cards off of Miranda’s body and read it to the suspect.