That Time the U.S. Military Had a Camel Corps

Camels have been used as beasts of burden for millennia and the creature is, in many ways, vastly more suited to the task than even the sturdiest of equids. For example, a typical camel can carry in excess of 300 kilos (661 lbs) of supplies without issue, more than twice the weight an average horse or mule could carry with similar distances/speeds. In addition, camels are also largely indifferent to relatively extreme heat, can go for days without needing to take in additional water, and can happily chow down on many desert plants horses and mules wouldn’t eat if they were starving (meaning more of what they can carry can be cargo instead of food for the animals). When not under heavy load, camels can also run as fast as 40 mph in short bursts as well as sustain a speed of around 25 mph for even as much as an hour. They are also extremely sure footed and can travel in weather conditions that would make wagon use impractical.

Camels have been used as beasts of burden for millennia and the creature is, in many ways, vastly more suited to the task than even the sturdiest of equids. For example, a typical camel can carry in excess of 300 kilos (661 lbs) of supplies without issue, more than twice the weight an average horse or mule could carry with similar distances/speeds. In addition, camels are also largely indifferent to relatively extreme heat, can go for days without needing to take in additional water, and can happily chow down on many desert plants horses and mules wouldn’t eat if they were starving (meaning more of what they can carry can be cargo instead of food for the animals). When not under heavy load, camels can also run as fast as 40 mph in short bursts as well as sustain a speed of around 25 mph for even as much as an hour. They are also extremely sure footed and can travel in weather conditions that would make wagon use impractical.

For this reason a small, but nonetheless dedicated group within the American military in the mid 19th century was positively obsessed with the idea of using camels as pack animals, and even potentially as cavalry.

It’s noted that the largest proponent of camel power at the time was the then Secretary of War, Jefferson Davis- yes, THAT, Jefferson Davis. Davis particularly thought the camel would be useful in southern states where the army was having trouble transporting supplies owing to the desert-like conditions in some of the regions.

To solve the problem, Davis continually pushed for importing camels, including in a report to congress he wrote in 1854 where he stated, “I again invite attention to the advantages to be anticipated from the use of camels…for military and other purposes, and for reasons set forth in my last annual report, recommend that an appropriation be made to introduce a small number of the several varieties of this animal, to test their adaptation to our country…”

Finally, in early 1855, Congress listened, setting a $30,000 (about $800,000 today) budget for just such an experiment. One Major Henry C. Wayne was then tasked with travelling all the way across the world to buy several dozen camels to bring back to America, with Wayne setting out on this trip on June 4, 1855.

Besides going to places like Egypt and other such regions known for their camel stock, Wayne also took a detour through Europe where he grilled various camel aficionados and zoological experts on how to best take care of the animal.

After several months, Wayne returned to America with a few dozen camels and a fair amount of arrogance about his new endeavor. On that note, only about four months after taking a crash course in camel care, Wayne proudly boasted that Americans would “manage camels not only as well, but better than Arabs as they will do it with more humanity and with far greater intelligence.” Of course, when initial efforts on that front demonstrated a little more experience was needed, various Arab immigrants who had experience managing the beasts were hired to head up the task.

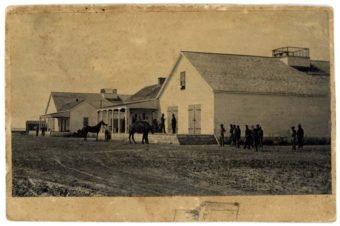

The newly formed United States Camel Corps quickly proved its worth, such as early on managing to carry supplies from San Antonio, Texas to Camp Verde, Arizona during a severe rainstorm that made using wagons practically impossible. In another expedition, the man in charge of the trip, Edward Fitzgerald Beale, afterwards reported back that just one camel was worth four of the best mules on that trip.

Robert E. Lee would later state after another expedition where conditions saw some of the mules die along the journey, the camels “endurance, docility and sagacity will not fail to attract attention of the Secretary of War, and but for whose reliable services the reconnaissance would have failed.”

Despite the glowing reviews, there were various complaints such as the camel’s legendary reputation for stubbornness and frequent temper tantrums and that horses were nervous around them. Of course, horses could be trained to put up with camels. The real issue seems to have been the human factor- soldiers just preferred to deal with more familiar horses and mules, despite the disadvantages compared to camels in certain situations. As Gen. David Twigg matter of factly stated: “I prefer mules for packing.”

Later, just as big of an issue was the fact that it was Jefferson Davis who championed the idea in the first place. As you might imagine, during and after the Civil War, ideas he’d previously prominently pushed for were not always viewed in the best light in the North.

Unsurprisingly from all this, the Camel Corps idea was quietly dropped within a year of the end of the Civil War and later, largely forgotten by history. However, some of the imported camels, including thousands imported by businesses around this same time that were rendered mostly useless with the establishment of the transcontinental railroad in the late 1860s, were simply set free, with sightings of wild camel still a thing in the South going all the way up to around the mid-20th century.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The North’s Air Force During the American Civil War

- That Time the U.S. Accidentally Nuked Britain’s First Satellite

- Are Camel’s Humps Actually Filled With Water?

- The U.S. Navy and Their Hilariously Inept Search for Dorothy and Her Friends

- The U.S. Military’s Proposed “Gay” Bomb

Bonus Facts:

- Male Arabian camels begin courtship via more or less inflating a portion of his soft palate called a dulla with air to the point that it protrudes up to a foot out of his mouth. The result is something that looks somewhat akin to an inflated scrotum hanging out of its mouth. On top of this, they use their spit to then make a low gurgling sound, with the result being the camel also appearing to foam at the mouth at the same time. If this isn’t sexy enough for the lady camels, they also rub their necks (where they have poll glands that produce a foul, brown goo) anywhere they can and even pee on their own tails to increase their lady-attracting stench.

- Even though today Camels can only naturally be found in parts of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, Camels are actually thought to have originated in the Americas around 40 million years ago. It’s thought that they migrated to Asia shortly before the last Ice Age, though there were still Camels in North America as recently as 15,000 years ago.

- America isn’t the only place that imported camels. Australia also imported up to 20,000 camels from India in the 19th century to help with exploring the country, much of which is desert. Ultimately many camels were set free and, unlike in the US, the camel population in Australia flourished. Today, Australia is estimated to have one of the largest feral camel populations in the world (estimated at 750,000 camels in 2009), which has since been deemed something of an environmental problem. As such, the government has set up a program to cull the camels, with around a couple hundred thousand being killed in the last several years in an attempt to control the population.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

One of the people who tried to interest the government in using camels was one of the most amazing unknown men of the 19th century – a Pennsylvania Quaker named Josiah Harlan. During the 1830s and 40s, as a consequence of a failed love affair back home, he sailed to India and served in the British Army in Burma as a surgeon. Tiring of that after a few years, he trekked across India, offered his services to the one-eyed Sikh Maharajah Ranjit Singh, and was enlisted to help return a deposed Afgan emir to the throne. Upon meeting the object of his coup, he switched allegiances to the sitting Emir after finding him much more intelligent, humane, and regal. His new BFF gave him a title and a small army and asked him to rid the northern Afghan frontier of pesky slave traders, which Harlan’s Quaker sensitivities also could not abide. He raised the American flag in the middle of the Hindu Kush, and was made an Afghan prince for life.

Kipling heard some of the stories of Harlan decades later, and thus the book, “The Man Who Would Be King.”

Deported by the Queen for messing about with all THREE of their foes in northern India, he returned to the US, wrote a book damning British imperialism, tried to talk Jefferson Davis into the aforementioned camels, and then ended up raising a Yankee regiment at the start of the Civil War. Ill and sickly, he was soon relieved of duty. He ended up practicing dentistry in San Francisco and died there pretty much penniless and unknown, in the early 1870s.

Wonderful history of the US Camel Corps. I loved this article.

You may already know the story of the most famous of the camel drivers, Hi Jolly, born Phillip Tedra in Syria, and later taking the name Hadji Ali referencing his completion of the pilgrimage to Mecca after converting to Islam.

Quartzite, AZ has a monument at the west of town marking his burial place, and commemorating his role in the camel corps experiment of the 1850’s. It’s certainly worth a visit.