The Truth About the Shortest Presidency

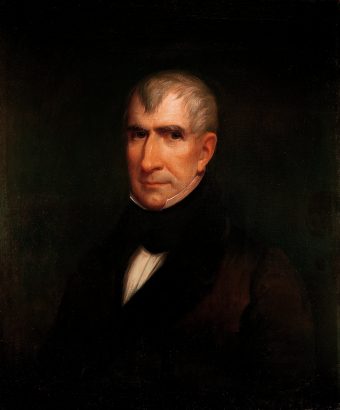

It was a wet, cold, wind overcast day on March 4, 1841. This didn’t matter to the thousands that had come out to the nation’s capital to see the president-elect William Henry Harrison be sworn into office as the 9th President of the United States. With people lining the streets all the way to the Capitol, it was described by John Quincy Adams as the largest crowd the city had ever seen and, by a historian later, as the most raucous celebration since George Washington’s 1789 inauguration. Despite his boring style and advanced age, Harrison’s military acumen while battling Indians in order to open western settlements earlier in the century had made “Old Tippecanoe” a populist candidate very much in line with the Andrew Jackson.

It was a wet, cold, wind overcast day on March 4, 1841. This didn’t matter to the thousands that had come out to the nation’s capital to see the president-elect William Henry Harrison be sworn into office as the 9th President of the United States. With people lining the streets all the way to the Capitol, it was described by John Quincy Adams as the largest crowd the city had ever seen and, by a historian later, as the most raucous celebration since George Washington’s 1789 inauguration. Despite his boring style and advanced age, Harrison’s military acumen while battling Indians in order to open western settlements earlier in the century had made “Old Tippecanoe” a populist candidate very much in line with the Andrew Jackson.

With temperatures in the mid-40s, Harrison rode through the streets not in a magnificent carriage that was built specifically for him, but – at his insistence – on a white horse. He wore no overcoat, gloves or hat because he felt it made him look undignified.

After being sworn in, he stepped to the podium and began his inauguration speech as such:

Called from a retirement which I had supposed was to continue for the residue of my life to fill the chief executive office of this great and free nation, I appear before you, fellow-citizens, to take the oaths which the Constitution prescribes as a necessary qualification for the performance of its duties; and in obedience to a custom coeval with our Government and what I believe to be your expectations I proceed to present to you a summary of the principles which will govern me in the discharge of the duties which I shall be called upon to perform.

Yes, that’s one very long sentence. His speech would go on to tally 8,445 words and take nearly two hours. To this day, it’s the longest inauguration speech in American history.

Exactly one month later, William Henry Harrison died – making him the first President to die in office and the shortest tenured president ever. While it’s often implied (and sometimes explicitly stated) that he died as a result of that lengthy speech in the cold, this doesn’t appear to be the case. He did not get sick until three weeks after his speech and it appears not from anything temperature related. (And if you’re curious, see Why Do People Seem to Get More Colds in the Winter?) His doctors didn’t help, regularly bleeding him with leeches, among other “treatments,” which we’ll get into shortly.

While Old Tippecanoe’s presidency was – unlike his inaugural address – very, very short, his life’s story was far from it.

At times during the campaign, Harrison would refer to himself as a child of the American Revolution. This wasn’t simply a boast, but also true. William was born as the youngest child to the wealthy and influential Harrison family of Virginia on February 9, 1773. Counted among family friends were famed names like Jefferson, Madison and Washington. Even more impressively, Benjamin Harrison (William’s father) was named a delegate to the Continental Congress and was an original signer of the Declaration of Independence (which note was not signed until August of 1776, not July 4th as is so often stated). Because of his family’s connections, there’s little doubt that young William met some of his Revolutionary heroes. In fact, with his father convinced that he was destined for a career in medicine, he was sent to Philadelphia to study under Benjamin Rush – another signer of the Declaration of Independence.

However, being a doctor was never the youngest Harrison’s destiny. When his father died in 1791, he joined the military and used his family name to secure an officer’s rank. He made his way to the Northwest Territory and worked under General “Mad Anthony” Wayne (named as such for his daring attack on the British during the Revolutionary War) at Fort Washington – near present-day Cincinnati. Harrison’s job there was to help Wayne open land for settlement, which meant fighting natives and forcing them from land that was deemed under American control. This is how Harrison began to make a name for himself – battling Native Americans.

When Wayne died, Captain Harrison took over military control of the Northwest Territory. In 1798, after resigning from the Army, he was named Secretary of the Northwest Territory by President Adams and its first delegate to Congress. In 1800, the territory split into two – the Ohio and Indiana Territory – and Harrison was named governor of the latter.

As governor, he was able to make himself a good deal of money through land speculation. But perhaps his worst offense was his exploitation of the Native population with a land grab that was driven by trickery and force. According to the Miller Center at the University of Virginia for the American Presidency, Harrison took advantage of the Native Americans inability to grasp the European idea of land ownership. He pushed for the signing of treaties that were written to intentionally confuse them. In addition, he exploited their inexperience with European alcohol (contrary to popular believe, Native Americans had various forms of alcohol before the Europeans arrived), using it to lower their inhibitions and having them accept deals that were pennies on the dollar. This eventually led to war with the Native American leader Tecumseh. On the banks of a small river in today’s Indiana called Tippecanoe, Harrison was able to fight off Tecumseh and his warriors mostly to due to overwhelming numbers and superior arms. Nonetheless, Harrison became the talk of the young nation for fighting off the “Indian insurrection.”

As the Miller Center puts it, “The Battle of Tippecanoe was good for William Henry Harrison and no one else.” In 1813, Tecumseh and Britain joined forces in attempts to embarrass Harrison and the United States during the western portion of the War of 1812. Again, Harrison’s outfit triumphed thanks in large part to simply having more men.

His military reputation followed him over the next two and half decades which allowed him to run and be nominated for various offices, including Congressmen, Senator and ambassador to Columbia. To many, it seemed Harrison’s ultimate goal was not public service, but to supplement a grandiose lifestyle. He moved in and out of debt numerous times in his career, often coming into money only to spend it right away. John Quincy Adams once said that he believed Harrison had a “rabid thirst for lucrative office.”

Nonetheless, in 1836 he was nominated by the newly formed Whig party to run for President (along with two other Whig candidates all with the intent to stop Martin Van Buren from becoming President). In 1840, he was nominated again with the express purpose of running against Jackson principles (which Van Buren represented). Despite Harrison’s own love for the finer things in life, he was presented as a direct contrast to the previous administration – a western man who was dull, lived in a log cabin and a military hero rather than a bureaucrat. This worked, despite it being ultimately false, and Harrison throttled Van Buren in the election, amassing nearly 80% of the electoral vote.

During the campaign, there were already hints that Harrison would not make it his full-term. He had been sick throughout the campaign, while also enduring the recent loss of a child. At the time, he was also the oldest person to be ever elected president. 150 years later, he would be eclipsed by Reagan (who was just out-olded by the recent election of Donald Trump).

On inauguration day, his very long speech detailed several things that are essentially his only Presidential record. He criticized the shift of centralizing power under the executive branch that had happened under Jackson and Van Buren, while claiming he would not run for a second term. Harrison said he would not interfere in the financial policies of the states, nor in their right to determine their own slaveholding laws. (Harrison was slaveholder himself.) He also pledged to pull the country out of the economic depression it was in.

It was three weeks after the inauguration that Harrison first told a doctor that he felt ill. Complaining of fatigue and anxiety, he was prescribed rest and various “medicines” that we would never ingest today (like acetate of ammonia and mercury-tinged liquids). Over a course of a week, Harrison gradually fell iller. His doctor was convinced that it was pneumonia, but his notes showed otherwise – with constant recordings of bowel movements and intestinal pain. On April 3, 1841, President Harrison uttered these (apparently) last words: “Sir, I wish you to understand the true principles of government; I wish them carried out, I ask nothing more.”

The legend has always been that Harrison had died from pneumonia contracted from refusing to wear a coat while spending hours in the cold and rain during his inauguration. However, in 2014, two doctors from the University of Maryland School of Medicine concluded that he likely died from enteric fever – or typhoid fever – as a result of drinking contaminated drinking water. During the mid-19th century, DC sewage was often dumped in a marsh that was located upstream of the White House’s water supply. It’s very possible that the bacteria-infused water seeped into the drinking water of the President, giving him the much-dreaded typhoid fever. As noted by the doctors, this poorly-designed White House architectural feature also may have been the cause of death President Taylor in 1850 and Lincoln’s son William in 1862.

Harrison’s quick death inspired a Constitutional crisis, as never before had a sitting President died while in office. The Constitution did not state with clarity what happens. It does say that the presidency “shall devolve on the Vice President” (which in this case was John Tyler), but it did not say if they would be simply the “acting” president until another was elected in a special election or they would become President until the next scheduled election. Tyler took the job and proposed these questions to the Supreme Court, Harrison’s cabinet and Congress. But no one would come to a clear, decisive, consensus-driven decision. So, Tyler decided that he would be President until the next election – which was four years later in 1844. He took a public oath of office on April 6th (three days after Harrison’s death). Detractors gave him the nickname “His Accidency.” It wouldn’t be until 1967 with the 25th Amendment that clear succession rules were put into law.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why Does the United States Use the Electoral College Instead of a Simple Vote Count When Deciding the Next President?

- Why Do Presidents Get to Pardon People at the End of Their Terms?

- Can a Vice Presidential Candidate or the Speaker of the House Really Be Elected President Instead of the Main, “Winning” Candidates?

- The First U.S. Presidential Assassination Attempt

- How a Donkey and an Elephant Came to Represent Democrats and Republicans

| Share the Knowledge! |

|