Jackie Robinson was Not the First African American to Play Major League Baseball

Myth: Jackie Robinson was the first African American to play in the Major Leagues

The great Jackie Robinson accomplished an amazing amount in his lifetime both on and off the field. Despite all the adversity and pressure he experienced, he somehow managed to put up legitimate Hall of Fame numbers doing what is often described as the hardest thing in all of sports- hitting a round ball with a thin round stick. One thing that he didn’t do, something that’s often credited to him, was become the first African American person to play in the Major Leagues. That was something that had been done at least three times before Robinson made his historic Major League debut on April 15, 1947.

Now if you happen to be a trivia buff and knew that already, odds are you think the first was actually Moses Fleetwood Walker, the second was his brother Weldy Walker, and you’re probably scratching your head trying to come up with the third. It turns out, that’s probably not correct either, although the verdict is still slightly out on the matter (being a very recent discovery).

The real first African American to play in the major leagues, and the only former slave to do so, is now generally thought to be a man by the name of William Edward White. Eighteen year old White, who at the time was a student at Brown, replaced an injured Joe Start in one single game in the Majors, playing for the National League Providence Grays on June 21, 1879. This was five years before Fleetwood Walker would make his Major League debut. In that game, White went 1 for 4 and scored a run in a game the Grays won 5 to 3.

While not a lot is known about White, what is known is that he officially claimed he himself was “white” and not of African heritage (his skin color apparently being light enough to pass as such). This is why up until very recently he wasn’t given credit for being the first African American to play in the Majors, with that honor going to Moses Fleetwood Walker.

This all changed when members of the Society for American Baseball Research, more commonly known as “SABR”, uncovered the fact that, according to an 1870 U.S. census, White’s mother was a woman named Hannah White, one of the 70 slaves owned by the person William White listed as his father according to Brown University’s records- Andrew Jackson White. Hannah’s other two children also appear to have been fathered by Andrew Jackson White. A.J. White also left the bulk of his estate to Hannah’s three children when he died, including William White, though he only acknowledged them as “the children of my servant Hannah”, rather than his own children.

In the context of solving the mystery of whether William White was the first African American to play in the Majors, the important bit in the Will is that he named William the child of Hannah, which backs up what the U.S. census stated. Thus, with the evidence at hand so far, it appears William White was the first African American to play in the Majors. As to why he never played again after that game, it isn’t known, but of course speculation is that his heritage was discovered, though it may have simply been that a better player was in the wings, as his replacement was future Hall of Famer Jim O’Rourke.

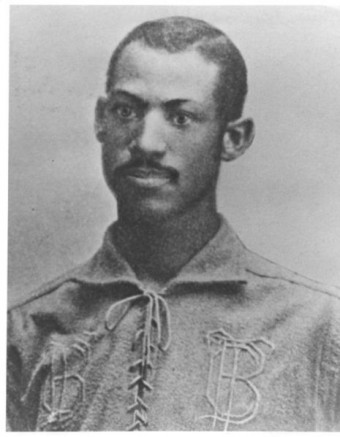

Whatever the case, the person long considered to have been the first African American to play in the Majors was, as mentioned, Moses Fleetwood Walker. Walker made his Major League debut on May 1, 1884 playing for the Toledo Blue Stockings against the Louisville Eclipse. He had been playing for the then minor league Blue Stockings when the team was added to the American Association, which later became the American League.

By all accounts, Walker was no less of an amazing player than the great Jackie Robinson, and is deserving of a lot of credit for what he went through during his time in the Majors. How good was he? Let’s just qualify the stats with the fact that Walker was a catcher… who caught without a glove or any other major protection, as was common at the time. Needless to say, catchers of the day were incredibly injury prone and rarely did well offensively because of the beating they took behind the plate.

Walker had it worse than most because many of the pitchers didn’t want to let a black man ostensibly tell them what to do by calling the pitches. As one pitcher, Tony Mullane, stated:

[Walker] was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked [the] Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals.

As a result, Walker was in the unenviable position of crouching behind the plate attempting to catch baseballs with no protective gear nor glove and not knowing the location nor what pitch was going to be thrown. Despite this, in his 42 games played in the Majors, he batted .263 (some accounts claim .264). Now that might not sound impressive, but you should consider the fact that this was well above average in his day- the rest of his team combined for an average of just .231 with the league average just .240 the season he played. Further, as catchers took an incredible beating (and still do today, though to a drastically lesser extent), most catchers typically batted between .100-.200 in his day. He was so good with his bat, that when he was too beat up to catch, they’d typically put him in the outfield so as not to lose his offensive production.

He also had to overcome the same type of obstacles as Jackie Robinson, including death threats, constant personal and physical attacks, and certain players refusing to play if Walker was allowed on the field, such as future Hall of Famer Adrian “Cap” Anson (the first major leaguer to accumulate more than 3,000 hits, finishing with 3,481). In fact, Fleetwood Walker’s brother, Weldy Walker, who also played in the Majors (5 games), blamed Anson for the banning of African American players in the Minor and Major leagues in the first place. (In truth, Anson’s despicable antics probably didn’t have nearly that much to do with it, though Anson was quite vocal about his opinions on the matter and not shy at all about trying to pressure others into advocating for the same stance.)

For instance, in Anson’s first encounter with Walker, Walker was supposed to have the day off, but when manager Charlie Morton heard that Anson and his team, the White Stockings, were refusing to play if Walker was allowed on the field, he put Walker in the lineup and told Anson that not only would they be forfeiting the game if they refused to play, but they’d also forfeit the money from ticket sales. Once money was brought into it, Anson and the White Stockings begrudgingly agreed to play.

After being injured to the point where he couldn’t bat, Fleetwood Walker’s Major League career ended up being over. Once he was healed up, he continued his career in the minors (which in 1887 boasted 13 African Americans despite rampant segregation). He also played in a few other leagues before finally both the National League and the American Association decided on their “gentleman’s agreement” to not sign any African American player, with that decision trickling down to other leagues that had not already instituted similar bans.

Robbed of the ability to play in the American and National Leagues as well as most others of any note at the time, Fleetwood Walker left baseball, as his brother also later did after playing and managing in a Negro league that ultimately failed. The two went on to various business ventures, at which they were seemingly quite successful, such as owning an operating a hotel, a movie theater, as well as a series of restaurants. Fleetwood Walker even attempted to get patents on a few different pieces of equipment he invented for showing “moving pictures”; he also held a patent for a certain type of exploding artillery shell. The two also became involved in politics with Weldy Walker serving on the Executive Committee of the Negro Protective Party, which was formed in response to the government turning a blind eye on the frequent lynchings that occurred at the time. The two also owned and operated the newspaper, The Equator.

I’ll close this with an excerpt from an open letter from Weldy Walker to the President of the Tri-State League published in The Sporting Life on March 14, 1888, after African Americans were officially banned from playing in those leagues when a law permitting them to be signed was repealed by the league:

…It is not because I was reserved and have been denied making my bread and butter with some club that I speak; but it is in hopes that the action taken at your last meeting will be called up for reconsideration at your next.

The law is disgrace to the present age, and reflects very much upon the intelligence of your last meeting, and casts derision at the laws of Ohio- the voice of the people- that say all men are equal. I would suggest that your honorable body, in case that black law is not repealed, pass one making it criminal for a colored man or woman to be found in a ball ground. There is now the same accommodation made for the colored patron of the game as the white, and the same provision and dispensation is made of the money of them both that finds its way into the coffers of the various clubs.

There should be some broader cause–such as want of ability, behavior, and intelligence–for barring a player than his color. It is for these reasons and because I think ability and intelligence should be recognized first and last–at all times and by everyone–I ask the question again, why was the “law permitting colored men to sign repealed, etc.?”

Yours truly, Weldy W. Walker

If you liked this article, you might also like:

- 20 Interesting Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Facts

- The 17 Year Old Girl Who Struck Out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig Back to Back and was Promptly Banned from the MLB and MiLB

- Abner Doubleday Did Not Invent Baseball

- 10 Fascinating Baseball Facts Part 2

Bonus Facts:

- While on the whole the Walker brothers did quite well for themselves financially in their lives after baseball, particularly considering the racial obstacles they had to deal with at the time, Fleetwood Walker was once attacked by a group of white men. During the ensuing melee, Walker killed one of the men, Patrick Murray. The remaining attackers attempted to kill Walker, but he escaped, though was later arrested and imprisoned. Somewhat surprisingly given attitudes at the time, on June 3, 1891 at the conclusion of his trial, a jury of all white men acquitted Walker on all charges.

- After the trial, Walker became convinced that black people would never be accepted in the United States and he and his brother began heavily advocating that all black people of African heritage return to Africa. Walker even published a book on the issue: Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America. This “back to Africa” stance is in small part why popular history has mostly swept Fleetwood Walker and his accomplishments under the rug.

- During one baseball game in college played in Kentucky, Fleetwood Walker at first had to sit out because the other team refused to play if he was on the field. However, the crowd was having none of this as his replacement catcher was awful compared to Walker. The crowd’s continual chanting for Walker ultimately forced the other team to allow him to play.

- Jackie Robinson: Race, Sports, and the American Dream, by Joseph Dorinson and Joram Warmund

- Moses Fleetwood Walker

- The Forgotten Mane: Moses Fleetwood Walker

- Cap Anson

- Black Baseball Pioneer William White

- Bill White

- William Edward White the First?

- Welday Walker Stats

- Welday Walker

- Welday Walker’s Letter

- Fleetwood Walker

- Breaking the Color Line

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

“Anson’s despicable antiques probably didn’t have nearly that much to do with it.”

Which antiques, his bed warmer, potbelly stove, and kerosene lantern? I think you mean “antics,” not “antiques.”

@SirLizard: You, sir, are a scholar and a gentlemen. Thanks for catching that. Fixed 🙂

what a great article.. thank’s very kindly for informing all of us of these wonderful facts, ball fans and history fans alike..!

what a great film the story of the Walkers would make, don’t you think?

“I’m not concerned with your liking or disliking me … all I ask is that you respect me as a human being.”

– Robinson, on his legacy

I have had to use this quote a couple of times in reader contributions and debate on different sports.

Wow! As a child we didn’t have catchers equip. and wouldn’t think of catching without it. Quite impressive. Even more impressive is the fact that he was catching for big leaguers.

I imagine that none of these men were “THE FIRST AFRICAN AMERICAN TO PLAY MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL.” If we are to incorrectly call Barack Obama the first African American President, then we should look for the first Major League Baseball player who was 50% or even 25% black, and they would be the first. In actuality, if we ever do actually have a Black President, Mr. Obama will be unmasked as the white man he actually is.

Um…what?

Quite possibly the most nonsensical paragraph I have ever read.

Throughout history, Black People have been systematically kept down by white people! This is why they are in their present condition throughout the world.They deserve a chance to reach their potential like everyone else.

What a racist/stupid thing to say. 10%, 50%, or 75%? Who gives a five-fingered fuck?

Satchel Paige was the first African american player.

Satchel Paige was born in 1906, Walker made his Major League debut on May 1, 1884. Sorry

we ArE a ConFUsEd SocieTy SocieTY?

It is time to give Moses Fleetwood Walker the credit he deserves?

We need a national campaign for “WE’RE ALL ON SAME TEAM” with website & symbol for the PEOPLE to express LOVE instead of HATE. I worked with the “Mad Men” in the Madison Avenue district in the sixties and I have applied my advertising, marketing & research skills to many projects throughout my life. I hope YOU will send this message/proposal to your contacts. Thank you for giving me the opportunity to send this message.