That Time the U.S. Made a Nuclear Gun

In the 1950s U.S. forces were stretched dangerously thin. U.S. President Dwight D Eisenhower stated of this, “My feeling…remains, that it would be impossible for the United States to maintain the military commitments which it now sustains around the world (without turning into a garrison state) did we not possess atomic weapons and the will to use them when necessary.”

In the 1950s U.S. forces were stretched dangerously thin. U.S. President Dwight D Eisenhower stated of this, “My feeling…remains, that it would be impossible for the United States to maintain the military commitments which it now sustains around the world (without turning into a garrison state) did we not possess atomic weapons and the will to use them when necessary.”

No surprise from this that, unsatisfied with the portability of their shiny new M65 nuclear cannons, which required a couple of very large trucks to transport, and further unsatisfied that firing it off in many tactical situations would be a bit like killing a mosquito with a hand grenade, in the late 1950s the U.S. military brass for once were thinking smaller. What they really wanted was a simple weapon that could launch a miniature nuclear warhead, could be carted around by a few soldiers, and be fired relatively quickly and reliably. This would allow a handful of soldiers to successful combat far superior forces on the other side, even at relatively close range, which none of the other nuclear weapons of the age could safely do- Enter the Davy Crockett.

Rumor has it the name was chosen in homage to the famed American politician owing to the legend that he once grinned a bear to death, with the idea referencing the association between Russia, and the Soviet Union in general, with bears.

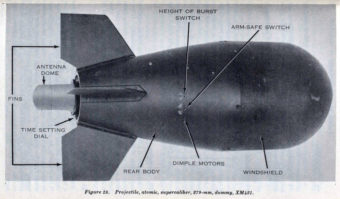

Whether that’s actually the reasoning behind the name or not, the first prototype of the Davy Crockett was completed in November of 1958 and ultimately deployed about two and a half years later in May of 1961. Featuring a variant of the W54 warhead contained in an M388 round, the projectile was fired from an M-28 or M-29 smooth bore recoilless gun. This was capable of launching the 10 or 20 ton yield nuke as far as about 1.25 miles for the M28 or 2.5 miles for the M29.

As for portability, the Davy Crockett could be either deployed and fired from the back of a jeep for maximum mobility, or even broken down into its components, with the pieces of the weapon carried by five soldiers on foot.

As for portability, the Davy Crockett could be either deployed and fired from the back of a jeep for maximum mobility, or even broken down into its components, with the pieces of the weapon carried by five soldiers on foot.

The general procedure for firing the 76 pound nuclear round was quite simple. First a spotting round would be shot from an attached gun to ensure the weapon was aimed reasonably well. After this, in order to get the nuke to end up more or less where the spotting round did, the angle of the gun would have to be adjusted. To do this, a small book with pre-calculated tables was carried giving adjustment figures for said angle.

However, it turns out test firings with non-live nukes showed again and again that the Davey Crockett was an obscenely inaccurate weapon, possibly both because of the angle adjustment and that the weapon itself was smooth bore. Of course, the fact that the Davey Crockett was shooting a nuclear warhead helped make this inaccuracy issue not as much of a problem as would be the case with other similar weapons.

Once the target was mildly locked on, the propellant charge would be inserted into the muzzle with a metal piston placed in after as a sort of cap. This was followed by the M388 round itself containing the W54 warhead. As the M388 was far too big to fit inside the bore, instead a rod would be attached to the back, with the nuke sitting at the front.

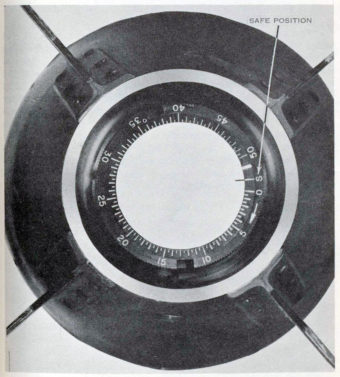

As for how the warhead would know when to detonate, there was a timer dial that would be set based on estimated distance to the target, using figures given in the aforementioned book containing a spreadsheet of tables.

As for how the warhead would know when to detonate, there was a timer dial that would be set based on estimated distance to the target, using figures given in the aforementioned book containing a spreadsheet of tables.

However, contrary to what is often stated, the timer was not actually the thing that triggered detonation. Rather, it simply armed the bomb once the time ran out. The actual trigger for detonation was a simple radar device in the back of the M388 that would detect how far above the ground the nuke was. There was also a high and low switch that could slightly adjust height of detonation based on the radar reading.

As you might have gleaned from all this, also contrary to what is often stated, this switch did not control the yield of the bomb, just what height it would detonate above the ground, roughly 20-40 feet AGL, depending on setting.

It should also be noted that, unlike many other nuclear weapons, this was an otherwise dumb nuke. Once the timer was set and it was fired, it would either go off or prove itself to be a dud. There was no aborting detonation after launch.

It should also be noted that, unlike many other nuclear weapons, this was an otherwise dumb nuke. Once the timer was set and it was fired, it would either go off or prove itself to be a dud. There was no aborting detonation after launch.

If all that is involved in firing the Davey Crockett sounds like it might take a long time, it turns out not at all given the destructive power of this weapon. One former Davey Crockett section soldier, Thomas Hermann, notes that they were actually trained and well capable of firing a nuke every two and a half minutes!

So just how deadly could this weapon be? While extremely low-powered as nukes go, the weapon nonetheless produced a blast in the ballpark of as large as the highest yield non-nuclear explosive devices of the era. But unlike many of these, it was relatively small and portable. More important than that was its potential for extended damage long after the initial blast. This was particularly useful when fired around critical routes that enemy soldiers would have to traverse. Not only would the initial blast do significant damage to any soldiers and enemy vehicles around at the time, but the radioactive fallout, which would almost certainly be fatal to anyone within about a quarter of a mile of the initial blast when it went off, would remain long after, making a given route, such as a mountain pass, impassable for several days after if one was interested in not dying of radiation poisoning. Naturally, the Soviets could defend against this simply by equipping each of their soldiers with lead-lined refrigerators, but for whatever reason they never seemed to have chosen to go this route.

On the other end of things, neither did the Americans. This was despite the fact that the Davey Crockett was also not terribly safe for those firing it. While 1.25-2.5 miles away is plenty of range to keep the soldiers who pulled the trigger safe from being harmed by the blast itself, in real world scenarios the enemy being fired upon could be closer and some of your own troops might also be even closer still.

Critical to all of this was also wind direction. With no wind, the radiation kill zone in the immediately aftermath of the blast was approximately 1,500 feet, but wind could easily blow dangerous radioactive particles towards one’s own troops. As such, crew were instructed to, if possible, only fire the gun when suitable cover behind a hill or the like was available to help reduce radiation exposure.

That said, presumably to try to get the soldiers operating the weapon to be slightly less hesitant about firing it, the instruction manual notes that the leader of the troop should instill a great sense of urgency in the soldiers operating the Davy Crockett and to remember that, to quote, “The search for nuclear targets is constant and vigorous!”

On top of that, the manual states that if the nuke failed to detonate for some reason, the soldiers should wait a half hour and then go and recover the supposed to be armed and ready to detonate at the whim of a radar trigger nuke…

Needless to say, while the Davy Crockett was deployed everywhere from West Germany to South Korea, with well over 2,000 of the M388 rounds made and 100 of the guns deployed, it was never actually used in battle.

That said, the Army did do one test fire of the Davy Crockett with a live M388 round. This occurred during Operation Sunbeam in a test code named “Little Feller I”, which took place on July 17, 1962. The nuke flew approximately 1.7 miles and detonated successfully about 30 feet above the ground, with an estimated yield of 18 tons from the blast. Interestingly enough, this was the last time the United States would detonate a nuke in the air close to the ground thanks to the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water. (And, yes, that is the real name of the treaty).

In the end, as cool as having a portable nuclear gun is and all, within only a few years the weapon would become antiquated, and by 1967 the Army was already beginning to phase it out, with it going the way of the Dodo completely by 1971. No doubt to the eternal relief of the soldiers tasked with firing the things should the need arise.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- That Time Five Guys Volunteered to Stand at Ground Zero of a Nuclear Blast Just to See What Would Happen

- Why is it Called Area 51?

- That Time the British Developed a Chicken Heated Nuclear Bomb

- For Nearly Two Decades the Nuclear Launch Code at all Minuteman Silos in the United States Was 00000000

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

It would appear those in the gaming community who’ve routinely talked shit about the absurdity of the Fat Man from Fallout might need to rethink their positions on how absurd such a thing actually is….