Chewing on Gum’s History

Gum is everywhere. It could be in someone’s pocket, in a woman’s purse, underneath a classroom’s desk or lining the checkout lines at the local grocery store. Or it could be in a person’s mouth- teeth chomping away on a stick that rapidly loses its flavor. Gum is one of the most ubiquitous confectioneries in our culture, yet few know its origins. So who invented gum and how did it become popular?

Gum is everywhere. It could be in someone’s pocket, in a woman’s purse, underneath a classroom’s desk or lining the checkout lines at the local grocery store. Or it could be in a person’s mouth- teeth chomping away on a stick that rapidly loses its flavor. Gum is one of the most ubiquitous confectioneries in our culture, yet few know its origins. So who invented gum and how did it become popular?

There’s some evidence that as far back as nine thousand years ago, ancient northern Europeans were chewing tree bark to help with toothaches. There’s also some evidence ancient Scandinavians chewed bark tar and the ancient Greeks enjoyed chomping away on different substances from various plants (some for their hallucinogenic properties).

But as Jennifer P. Mathews, author of the book Chicle: The Chewing Gum of the Americas, notes, modern gum’s more direct history starts a little later – with the Mayans and chicle, a natural latex resin that comes from the sapodilla trees that are native to southern Mexico and Central America. The tree produces this substance as a mechanism to protect itself from insect attacks, with the resin both trapping invaders in the sticky substance as well as helping heal its wounds from such attacks.

It would seem that since the beginning of Mayan civilization some 3,500 years ago, they recognized that this resin was good for chewing due to being odorless, mostly tasteless, not poisonous and containing water droplets. While on a hunt, it was particularly a great, readily accessible way to stave off hunger and thirst.

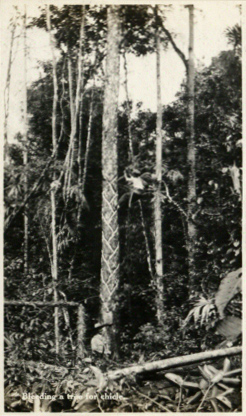

As the Mayan civilization matured over the millennia, they learned better ways to collect and prepare chicle. For instance, they developed a way of cutting into the tree in a zigzag pattern still used today that allowed the resin to flow and be collected more easily. The Mayans also figured out a better way to preserve and prepare it by drying and cooking the resin.

As the Mayan civilization matured over the millennia, they learned better ways to collect and prepare chicle. For instance, they developed a way of cutting into the tree in a zigzag pattern still used today that allowed the resin to flow and be collected more easily. The Mayans also figured out a better way to preserve and prepare it by drying and cooking the resin.

Hundreds of years later, the Aztecs (who were at their height from about 1200 to 1521) were also enjoying chicle. Much like today, a few social edicts were developed around chewing the gum. For example, it was only appropriate for unmarried women and children to chew chicle in public. Married women could only chew in private, which they would do mostly for health reasons (tooth decay) or bad breath. Men would sometimes do this as well, but if an Aztec man was caught chewing in public, he was regarded as “effeminate” or a “sodomite” (this according to the observations of a 16th-century Spanish missionary, Bernardino de Sahagún). On this note, chewing chicle in public was a way to identify someone’s sexual and marital status in Aztec culture. For example, there’s evidence that one could identify women who were prostitutes by their suggestively smacking their lips on a chewed piece of chicle.

As with most things that were developed in North America centuries ago, the chewing of chicle was co-opted by European settlers. By the early 19th century, the habit of chewing on resin from local trees had made its way north.

For example, when Maine-native John Curtis was a young boy, he fondly remembered cooking spruce resin into gum with his father over the kitchen stove. While originally only a family recipe, Curtis felt it could have wider appeal. In 1848, he became the first to produce and commercialize spruce gum. (Before this, certain Native American groups were known to use the resin from spruce trees for not only chewing, but for repair work, as a form of glue).

For example, when Maine-native John Curtis was a young boy, he fondly remembered cooking spruce resin into gum with his father over the kitchen stove. While originally only a family recipe, Curtis felt it could have wider appeal. In 1848, he became the first to produce and commercialize spruce gum. (Before this, certain Native American groups were known to use the resin from spruce trees for not only chewing, but for repair work, as a form of glue).

Beyond simply boiling and cleaning the resin, Curtis cut them into strips, bathed them in cornstarch so they wouldn’t be too sticky and wrapped each individual strip in tissue paper. Calling it “State of Maine Pure Spruce Gum,” it was extremely popular – so much so that within four years he had built the world’s first chewing gum factory in Portland, Maine.

However, two things limited Curtis’ impact on the history of gum. First, the spruce tree was also a favorite of the newspaper industry and many were earmarked for this purpose, causing Curtis’ sources to dry up fairly quickly. In addition, spruce gum simply didn’t taste that good.

While, at the time, it had little competition on the market, the public was waiting for a better alternative. When Thomas Adams introduced chicle to the American public, it knocked Curtis out of business.

The story of how chicle originally made its way into the mouths of US citizens in the late 19th century is full of legend, lack of clarity and names that history connoisseurs may recognize. While he was born in New York City, a few accounts say that Thomas Adams Sr. was related to the much more well-known Massachusetts Adams family (two of which were US presidents). He sort of floated through life, eventually becoming an amateur inventor and glasssmith.

Seemingly by happenstance, he befriended a fellow New Yorker named Rudolph Napegy, who wasn’t a particular historical figure in and of himself. But he had recently gotten a job as the US secretary and English interpreter for the legendary exiled Mexican president General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna.

By this point, around 1857, Santa Anna was mostly broke and living in disgrace in Staten Island, having been exiled from Mexico. He was the general who had crushed the Texan rebellion two decades earlier at the “Battle of the Alamo,” only to be defeated himself in April of 1836 when his overconfidence got the best of him. After that, even though he served six more terms as Mexican president, Santa Anna’s reputation was never fully restored. When he hired Napegy to be his English interpreter, he was a long way from home with funds dwindling.

While the exact details have never been clear, it seems Santa Anna had brought a whole lot of chicle with him from Mexico. At some point, Adams picked up a bunch of chicle from his friend Napegy and tried to vulcanize it (the process of vulcanization had been patented by Charles Goodyear over a decade before, see: The Luckless Rubber Maven: Charles Goodyear), perhaps even with the encouragement of Santa Anna; rumor has it Santa Anna was hoping to use a vulcanized version of the product to get the money necessary to fund a coup in Mexico, installing himself once again as leader.

Whether that latter part of the story is true or simply legend, all attempts to vulcanize the substance failed. With Adams’ plan to introduce a drastically cheaper substitute for vulcanized rubber to the world in the trash bin, he began thinking he should just throw the lot of it “into the East River.” But then, he happened to go into a drug store and overheard a kid ask for spruce or paraffin wax gum. It finally dawned on Adams that chicle didn’t need to be reinvented as an alternate form of rubber, but rather should be used like it had been for thousands of years – as chewing gum.

The first chicle-based chewing gum debuted in America in 1859 thanks to Adams. Within a decade, other American-companies were tapping trees in Mexico to sell their own version of chicle gum. In the late 1880s, Adams had built the world’s largest gum planet near the Brooklyn Bridge which made five tons of chewing gum daily including their best seller Tutti-Frutti

William Wrigley wasn’t the first gum maven. In fact, gum wasn’t even his original business. He started out in the late 19th-century selling soap, a business he had inherited from his father. Selling soaps in Chicago proved to not be a great business, so Wrigley added encouragement to store owners to stock his product – with every order of soap, he threw in a free can of baking powder (which was a house necessity in the late 19th century). As it turned out, merchants liked the baking powder more than the soap, so Wrigley started selling that instead.

Using the same marketing ploy as before, he gave away a freebie – but this time it was chewing gum. In 1893, Wrigley introduced Juicy Fruit (See: What is the Juice in Juicy Fruit?) and realized that gum was his future. When Wrigley died four decades later, he was one of the richest men in America (while also owning the baseball team the Chicago Cubs, which he bought in 1921). His empire was built on a freebie that turned into his staple product- chewing gum. (You can learn much more about Wrigley in our article here: From Scouring Soap to Chewing Gum- William Wrigley Jr. and His Freebies)

As the years went on, demand for chicle-based chewing gum increased but the supply of sapodilla trees in which the chicle came from decreased. By the 1930s, a quarter of Mexico’s sapodilla trees had been killed due to unsustainable harvesting methods. If that pace had kept up, these trees would had gone extinct by the 1970s- somewhat ironic given the tree evolved to produce the resin to protect itself. Fortunately for the trees, in the mid-20th century, most gum manufacturers had switched to synthetic ingredients for chewing gum, including strips made out of petroleum, wax and other substances. By 1980, the United States had stopped importing chicle from Mexico altogether. Today, there are still a few chicle-based chewing gums out there, but they are few and far between.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Inventing Bubble Gum

- Changing the World One Package at a Time- The Invention of the Cardboard Box

- The Rubber Band: Holding It Together Since 1820

- Why Seaweed is Sometimes Used in the Making of Ice Cream

- The Truth About Aspartame and Your Health

- “Chew on This: The History of Gum – History.com

- “A Brief History of Chewing Gum” – Smithsonian Magazine

- Chicle: The Chewing Gum of the Americas, from the Ancient Maya to William Wrigley by Jennifer P. Mathews

- “FROM SCOURING SOAP TO CHEWING GUM- WILLIAM WRIGLEY JR. AND HIS FREEBIES” – Today I Found Out

- “Chicle’: A Chewy Story Of The Americas” – NPR

- “Chicle” – Encyclopedia Britannica

- “Aztecs” – History.com

- “Bernardino de Sahagún” – New Advent

- “John B. Curtis” – Chewing Gum Facts

- “Curtis & Son Gum Factory” – Greater Portland Landmarks

- “Chewing Gum: The Fortunes of Taste” by Michael Redclift

- “Owners” – Chicago Cubs

- “William Wrigley Jr.” – Wrigley.com

| Share the Knowledge! |

|