The Lawrence Massacre of 1863

Kansas had been swept up in the debate over whether or not it should allow slavery for some time. When it was finally decided that Kansas would be a free state, the South was sore. There were many clashes at the border between northern and southern states during the Civil War, and Lawrence was almost always ready to defend its town. However, as the months wore on and the alarms sounded without any sign of Confederate troops, the citizens of Lawrence began to feel safe and secure in their homes.

Shortly before August of 1863, the officials in the town were informed that a growing band of rebels was setting up camp just outside of Lawrence. Despite the Mayor sending for reinforcements and artillery “just in case,” help didn’t arrive fast enough, and the people of Lawrence believed they were safe without it. They didn’t think the rebels would be able to break through the military line at the border of Kansas, and even if they did, they wouldn’t be able to get to Lawrence without someone raising the alarm.

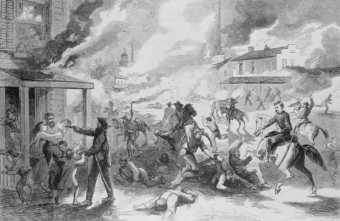

In the early morning of August 21, 1863, William Clarke Quantrill and a band of over 400 confederate soldiers rode into the small, sleepy town of Lawrence, Kansas. Though the band had marched that afternoon and into the night, no one had ridden to Lawrence to inform them of the impending attack. Barely anyone stirred at first as the rebels began to lay the town to waste: they set buildings on fire, broke into homes and stores and ransacked them, and, as people began to wake up, shot at innocent civilians who had not been warned of the attack.

One of the first men killed was Reverend Snyder. Mayor George Collamore initially escaped the carnage by hiding in his well—where he died of smoke inhalation. When the rebels left, one of the surviving men, who was a friend of the mayor’s, went down the well to find him. The rope supporting him broke, and he died too. In addition to these people, the rebels heavily targeted free black men.

The raiders left by nightfall, leaving a wake of destruction behind them. All in all, over 150 Lawrence men were killed, leaving at least 80 women widows and 250 children fatherless. The cost of destruction is estimated to have been between $1 million and $1.5 million dollars or about $23 million today.

The Lawrence Massacre has been the subject of debate since, particularly whether it can rightfully be called a massacre, or simply another battle in the bloody Civil War. Whatever the case, the question remains: why Lawrence? And why August 21, 1863? There had been plenty of other opportunities to raid the town, and the people of Lawrence hadn’t seen any action before.

It is thought by some historians that it was an act of revenge after a women’s prison in Kansas City collapsed, killing four inmates, just over a week before the massacre. Among the dead were relatives of the men who participated in the slaughter of Lawrence residents: a sister of William T. Andersen, and a cousin of Cole Younger.

These women had been put away as part of a Union effort to round up women suspected of aiding Confederate troops. Many of them were arrested for arbitrary reasons such as that they had bolts of cloth that might have been used to make Confederate uniforms, while others were taken to serve as hostages. After the building collapsed, rumours spread that the collapse had been intentional, spurred on by drunken guards who openly proclaimed that they had taken out the building’s support beams in order to collapse the structure.

Needless to say, these rumours didn’t sit well with the relatives of the women killed, nor Confederate men who saw it as their duty to protect southern women.

In addition, William Quantrill himself had ties to Lawrence—he had lived there under an alias just a few years before the attack. It’s possible that this connection contributed to him choosing this specific town, as knowledge of the town gave him the upper hand. For instance, many of his men went at once to Mayor Collamore’s house in order to prevent any of the townsfolk rallying there.

Despite the attackers claiming that revenge was the true motive behind the Lawrence attack, many did not feel that they were justified in doing so. The true cause of the prison collapse is still unknown. Though the guards had admitted to pulling the support beams, they had been drunk at the time and weren’t taken seriously by most people. Other theories are that a strong gust of wind blew it over, feral hogs rooting around made the foundation unstable, and even that the women inside had been tunnelling through the floors to escape.

Whatever the case, the Confederate raiders left a mess in their wake, and they never served time for their crimes. However, there were some measures taken by Kansas to prevent another such massacre: the residents of the counties on the border had to relocate to Kansas City for a while. Thomas Ewing, who issued what was known as Order No. 11 on August 25, 1863, believed that this would flush out the guerrillas and cut off their supply lines—and, most importantly, take the innocent civilians off the front line.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Largely Forgotten Paris Massacre of 1961

- The Acoustic Shadow and the American Civil War

- The North’s Air Force During the American Civil War

- The Last Veteran of the Civil War

- The U.S. Army’s Camel Corps

| Share the Knowledge! |

|