August 6, 1855- Bloody Monday

This Day In History: August 6, 1855

Monday, August 6, 1855 was an election day in Louisville, Kentucky. The political field looked a bit different then, with the two main parties being the Democrats and the Know-Nothings (an offshoot of the Whig Party), but they faced a lot of the same issues that the Democrats and Republicans do today- they just didn’t get along. An election is enough to get anyone’s blood boiling, and back in 1855 a number of issues came to a head, resulting in some of the worst riots in Louisville history.

Monday, August 6, 1855 was an election day in Louisville, Kentucky. The political field looked a bit different then, with the two main parties being the Democrats and the Know-Nothings (an offshoot of the Whig Party), but they faced a lot of the same issues that the Democrats and Republicans do today- they just didn’t get along. An election is enough to get anyone’s blood boiling, and back in 1855 a number of issues came to a head, resulting in some of the worst riots in Louisville history.

The Know-Nothings were also called “American Nativists.” It was largely comprised of white protestants whose families had already laid down their roots in the United States. They considered themselves to have old American blood, however old American blood could be at the time. The Democratic Party, on the other hand, attracted a lot of the recent Irish and German immigrants who were mostly Catholic. Thousands of immigrants had settled in Louisville and the Know-Nothings weren’t very happy about it. They thought that the immigrants would “undermine the American way of life.”

Over a decade before Bloody Monday, the German editor of a Louisville newspaper urged his fellow immigrants to assert their right to vote by arming themselves as they headed to the polls to vote in the 1844 presidential election. The editor was later forced to flee after native-born U.S. citizens gathered in front of his office, but the “damage” was done. James K. Polk, a Democrat, won the election instead of Kentucky Senator Henry Clay, a member of the Whig party. The result of the election was blamed on the votes of German and Irish immigrants.

By 1849, a group called the National Central Union of Free Germans (NCUFG) was headquartered in Louisville, urging immigrants to retain their native language and customs. The NCUFG also promoted “wild” notions like women’s suffrage, the abolition of slavery, and equality for black men. The party that would soon be known as the Know-Nothings were infuriated because the immigrants weren’t conforming to their idea of how Americans should behave or think.

By 1852, the Whig party dissolved, divided over the issue of slavery. The Know-Nothing Party was officially formed, named because when asked about what their organization did, members were told to say “I don’t know” in order to keep business secret. In truth, one of their main goals was to keep Catholics out of office, as they feared the power of the Pope an didn’t want the Catholic Church to butt in on American business. They were successful. On April 7, 1855, Know-Nothing John Barbee was elected Mayor of Louisville and by early May the party had infiltrated the county’s city hall.

About a month before Bloody Monday, a mob searched a local Catholic church for weapons they believed were stored there, but they didn’t find anything. A few days later, almost all of the Catholic teachers were fired by the Louisville Public School Board. In a local newspaper, George Prentice called his fellow United States citizens to arms in an advertisement that might intimidate the staunchest of immigrants: “Let the foreigners keep their elbows to themselves to-day at the polls. Americans are you all ready? We think we hear you shout ‘ready,’ ‘well fire!’ and may heaven have mercy on the foe.” On the day of the election, the Know-Nothing party took control of the polls by setting up thugs at the doors and demanding to see yellow tickets—a sign that the person was with the Know-Nothing Party. All of these actions were backed up by the Louisville city police.

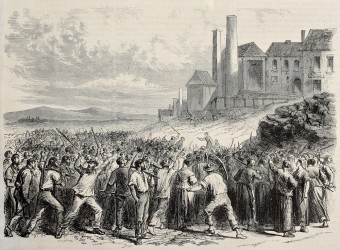

Needless to say, the immigrants weren’t exactly happy about being prevented from voting. One man, George Berg, was beaten to death by a group of angry Irishmen, while a German man fired shots at a passing carriage on the corner of Shelby and Green Streets. After the first shots were fired, the Know-Nothings came out in uncontrollable mobs. They burned a whole row of houses in the Irish district, burning several people to death and hanging a few more before tossing the bodies into the flames. An old Irishman was pulled from his bed and killed for “being an Irishman and a Catholic.”

To his credit, Mayor John Barbee, despite being a Know-Nothing himself, saved two Catholic churches from destruction and called for an end to the bloodshed. As the riots wound down, many Irish and German immigrants were taken to jail, though no one was ever convicted of any crimes. All in all, about 22 people were killed, many more injured, and dozens of buildings had burned down. Most of the dead were Irish and German, making it likely that the Know-Nothings did more damage than those they took to jail. It was one of the deadliest social riots in Louisville history. Though he wasn’t officially charged, George Prentice faced a lot of backlash after the riots because people believed that the articles in his newspaper urged people to fight, so many, seeking someone to point the finger at, blamed him for starting the riots.

Obviously, the Know-Nothings won the election since they wouldn’t let anyone supporting the other party in to vote. The riots and the election outcome caused over 10,000 immigrants to pack up their bags and high-tail it out of Louisville.

The Know-Nothings disbanded just a few years later in 1857, torn over the issue of slavery. As for the people of Louisville, a decade after Bloody Monday, they elected a German mayor.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why We Have a 7 Day Week and the Origin of the Names of the Days of the Week

- One of the Great Practical Jokes of the 19th Century, the Berners Street Hoax

- Abraham Lincoln Established the Secret Service the Day He was Assassinated

- The Origin of the American Democratic Party

- John Wilkes Booth’s Brother Saved Abraham Lincoln’s Son’s Life

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Barbee only acted to save the Catholic churches after Bishop Spalding let him know how bad things were going to be if one of his churches were burned. Give Barbee credit for having common sense, but he was no hero of the day. There is much left out of this piece of the violence enacted upon the German & Irish.