That Time Teddy Roosevelt Got Shot in the Chest But Gave a 90 Minute Speech Anyway

To most of the approximately 10,000 people packed into Milwaukee Auditorium on October 14, 1912, nothing seemed out of the ordinary in the moments before Teddy Roosevelt was scheduled to give what was supposed to be a simple campaign speech. The former President of the United States was running for a near unprecedented third term, this time as the Progressive Party candidate. However, when Roosevelt stepped onto the stage with a sort of wobble, his friend and fellow Progressive Party member, Henry Cochems, felt obligated to tell the audience what had happened – Roosevelt had been shot only moments before.

To most of the approximately 10,000 people packed into Milwaukee Auditorium on October 14, 1912, nothing seemed out of the ordinary in the moments before Teddy Roosevelt was scheduled to give what was supposed to be a simple campaign speech. The former President of the United States was running for a near unprecedented third term, this time as the Progressive Party candidate. However, when Roosevelt stepped onto the stage with a sort of wobble, his friend and fellow Progressive Party member, Henry Cochems, felt obligated to tell the audience what had happened – Roosevelt had been shot only moments before.

Most people were stunned, while others couldn’t believe it – one person even reportedly yelled “Fake!”

Chuckling, Roosevelt opened his coat to reveal a bloodied and bullet-pierced shirt. An audible gasp was heard as Roosevelt advanced to the podium. Proving yet again, he was determined to make men everywhere feel a little less manly, he stepped up and started what would become a 90-minute speech, in spite of his injury. He began with, “Friends, I shall ask you to be as quiet as possible. I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot; but it takes more than that to kill a Bull Moose.”

So who shot Roosevelt? Why was he so determined to give his speech anyway? And why was the famed Republican president now running under the so-called “Bull Moose” ticket?

When Teddy Roosevelt left office in 1909, he was thankful to leave the White House under the care of good friend, William Taft – who had been elected the next President of the United States by a substantial electoral margin in large part owing to his promises to continue Roosevelt’s programs and agenda.

But the now ex-president always had this nagging feeling that perhaps he should have run for President again in order to ensure said progressive policies would not fall by the wayside. By the time the 1912 election rolled around, Roosevelt’s suspicion was confirmed. At least in Roosevelt’s mind, Taft had betrayed him and many of the things Roosevelt had fought for in his years as president.

As such, Roosevelt lashed out at the president, calling him a traitor and challenging him as the 1912 Republican nominee for President. As the election season continued, Roosevelt became the favorite. However, despite Roosevelt winning a majority of the primary votes, Taft was awarded the Republican nomination seemingly due to his ability as president to give out federal patronage – essentially favors for votes.

Dismayed by this corruption, Roosevelt formed his own party – the Progressive Party or the “Bull Moose Party” – and gave himself the nomination. Meanwhile, the Democrats, were obviously ecstatic at the Republican chaos- after all, a split in Republican votes meant for the first time in a long time they had a great shot at the White House. As such, they nominated New Jersey governor Woodrow Wilson, who, interestingly enough, was a lot closer in policy to Roosevelt than Taft.

In the end, it was a four-way race: Roosevelt, Wilson, Taft and the Socialist Party’s Eugene Debs. Not one to go half-way on anything (again, see: In Which Teddy Roosevelt Makes Men Everywhere Feel a Little Less Manly), he visited 38 states on the campaign trail to ask citizens to vote for him – more than all of his opponents combined.

This brings us to October 14th, which started as most others had for Roosevelt in 1912, with him on the move. He began the day in Chicago, then moved to Racine, Wisconsin before heading south to Milwaukee for a nighttime address to an expected large crowd.

Roosevelt’s voice was nearly gone when he stepped out of the Hotel Gilpatrick wearing his Army overcoat to combat the fall chill that was in the air. Inside his breast pocket was his neatly double-folded 50-page speech for the evening (after all, Roosevelt was anything but concise) along with an eyeglass case.

As he hustled to a waiting car, a roar erupted from bystanders upon noticing the former President was in their midst. Roosevelt turned around and, with his hat in hand, waved to the crowd. All of sudden, a loud pop and a puff of smoke was seen as a bullet erupted from a Colt .38 revolver on its way into Roosevelt’s chest.

John Schrank was a New York City saloon owner until he decided that it was his duty to kill “Colonel Roosevelt.” In a later confession, he said that he had at one time admired Roosevelt, but began to think ill of him when he showed his interest in running for a third term. He felt strongly that, “Any man looking for a third term ought to be shot.”

He also would confess that,

I was convinced that if he was defeated at the Fall election he would… cry ‘Thief’, and that his action would plunge the country into a bloody civil war. I deemed it my duty, after much consideration of the situation, to put him out of the way. …

I had a dream in which former President McKinley appeared to me. I was told by McKinley in this dream that it was not Czolgosz who murdered him, but Roosevelt. McKinley… told me that his blood was on Roosevelt’s hand, and that Roosevelt had killed him so that he might become President.

I was more deeply impressed by what I read in the newspapers than others, and after having this dream was move convinced than ever that I should free the country from the menace of Roosevelt’s ambition.

And so it was that on September 21st, his stalking pursuit of Roosevelt began when he bought a steamer ticket to Charleston. From there, he continued to follow his target for weeks, traversing the country along with him – from Charleston to Atlanta to Chattanooga to Evansville to Indianapolis to Chicago to, finally, Milwaukee. As Schrank noted in his confession, at each stop he was either foiled by a change in Roosevelt’s schedule or Schrank’s own cowardice. In Milwaukee, however, neither got in his way.

I came to Milwaukee Sunday morning and went to the Argyle, a lodging house on Third Street. I then purchased newspapers to inform myself as to Roosevelt’s whereabouts and learned on Monday that he was to arrive at 5 o’clock. I learned also that he was to be a guest a the Gilpatrick, and managed to gain a position near the entrance where I could shoot to kill when Roosevelt appeared.

Schrank was only five feet away from Roosevelt when he shot him in the chest. As Roosevelt stumbled back, the candidate’s stenographer put Schrank in a headlock and pushed him to the ground. While concern was obviously directed at Roosevelt, the crowd went after Schrank – kicking and punching the would-be assassin.

As would later be revealed, the massive bulge of the 50-page speech and his hard leather eyeglass case in his breast pocket- not to mention Roosevelt’s famously ample chest muscles- prevented the bullet from doing significant damage.

As would later be revealed, the massive bulge of the 50-page speech and his hard leather eyeglass case in his breast pocket- not to mention Roosevelt’s famously ample chest muscles- prevented the bullet from doing significant damage.

After an initial stumble, he coughed into his hand to check for blood. When none came up, he felt sure that the bullet had not pierced his lung. “He pinked me,” he said to one of his aides.

Schrank was whisked away in a paddy wagon (followed by a group of people yelling “lynch him”). He would later plead guilty, stating, “I am sorry I have caused all this trouble for the good people of Milwaukee and Wisconsin, but I am not sorry that I carried out my plan.” He was eventually determined to be “insane” and would live out his days at a Wisconsin asylum until his death 31 years later in 1943.

As for Roosevelt, those with him demanded that he go to the hospital, but that wasn’t really Roosevelt’s style; he refused and told the driver to take him to his scheduled speech.

Once there, three doctors examined him backstage, found the dime-sized hole where the bullet had pierced him and a patch of blood. They likewise implored him to get to a hospital, but he insisted he had a speech to give. However, he did take time out to send a telegram to his wife saying he was in excellent shape and that the wound wasn’t “a particle more serious than one of the injuries any of the boys used continually to be having.”

Nevertheless, walking onto the stage, he reportedly was pale and unsteady, and admitted to the crowd, “The bullet is in me now, so that I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.” He then proceeded to talk for about 90 minutes…

The bulk of his speech was railing against Wilson, saying that a majority of the trusts that Roosevelt worked so hard to rid the country of were organized in New Jersey – Wilson’s home state.

About 30 minutes into his speech, his campaign manager gently tried to get him to stop, but Roosevelt remarked, “My friends are a little more nervous than I am. Don’t you waste any sympathy on me.”

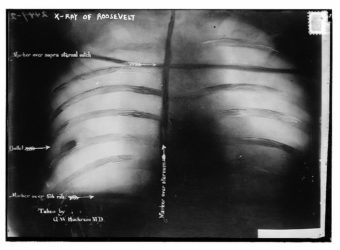

As noted, he continued for almost another hour after this. Finally, he finished to great applause and headed to the hospital. After an X-ray was taken, it was found that the bullet was lodged next to a rib in his chest. It stayed there the rest of Roosevelt’s life.

As noted, he continued for almost another hour after this. Finally, he finished to great applause and headed to the hospital. After an X-ray was taken, it was found that the bullet was lodged next to a rib in his chest. It stayed there the rest of Roosevelt’s life.

This was probably for the best, as, contrary to what is often depicted by Hollywood, leaving the bullet in his generally better than trying to remove it, even today. Back then, this was even more the case due to increased risk of infection, which was what eventually claimed the lived of President James Garfield and Roosevelt’s own predecessor, President William McKinley, when they had their own meetings with assassins’ bullets. Thus, choosing to essentially do nothing, may have saved Roosevelt’s life.

Whatever the case, a week later, Roosevelt was out the hospital and back on the campaign trail. In a show of respect for Roosevelt, his opponents chose to cease their own campaigns while he was in the hospital, despite being so close to election day.

In the end, Wilson ended up winning the 1912 election because Roosevelt and Taft split the Republican vote, with Wilson getting 42% of the popular vote, while Roosevelt (27%) and Taft (23%) combined for 50%. But the ex-president had no regrets, not even about the assassination attempt. Explaining his thinking to a friend years later about his decision to go forward with the speech, “In the very unlikely event of the wound being mortal, I wished to die with my boots on.”

Or as he explained in his speech directly after being shot, when whether he would die or not was still uncertain,

I want you to understand that I am ahead of the game, anyway. No man has had a happier life than I have led; a happier life in every way. I have been able to do certain things that I greatly wished to do, and I am interested in doing other things. I can tell you with absolute truthfulness that I am very much uninterested in whether I am shot or not. It was just as when I was colonel of my regiment. I always felt that a private was to be excused for feeling at times some pangs of anxiety about his personal safety, but I cannot understand a man fit to be a colonel who can pay any heed to his personal safety when he is occupied as he ought to be with the absorbing desire to do his duty.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- 5 Fascinating Vice-Presidents You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

- The Real Story Behind How Teddy Bears Got Their Name

- The Tragic Life of JFK’s Sister

- Does the U.S. President’s Dog Get Its Own Secret Service Agents?

- Why Does the United States Use the Electoral College Instead of a Simple Vote Count When Deciding the Next President?

- “Shot in the Chest 100 Years Ago, Teddy Roosevelt Kept on Talking” – History.com

- “John Schrank’s Letter on the ‘Third Term” -Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace Historical Site, NPS

- “Who Shot T.R.?’ – Theodore Roosevelt Birthplace Historical Site, NPS

- “The Speech That Saved Teddy Roosevelt’s Life” – Smithsonian Magazine

- “It Takes More Than That to Kill a Bull Moose: The Leader and The Cause” – Theodore Roosevelt Association

- “Glass Used by Teddy Roosevelt after Assassination Attempt” – Wisconsin Historical Society

- “Would-be Assassin is John Shrank, Once Saloonkeeper Here” – The New York Times, October 14, 1912

- “Coach dropped career to help TR” – The Bismarck Tribune

- “WILLIAM TAFT: CAMPAIGNS AND ELECTIONS” – UVA, Miller Center

- Assassination Bullet Image Source

- John Flammang Schrank

- First Presidential Assassination Attempts

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

The topic itself looks very surprising but Teddy Roosevelt gave an one and a half hour speech after being shot in chest. No one can even imagine how would he even manage that and how much he felt pain. 🙁