Can Sharks Really Grow an Unlimited Number of Teeth?

While sharks aren’t exactly the ruthless predators most Hollywood features make them out to be (see: Do Sharks Really Not Like How Humans Taste?), they do possess a number of frighteningly efficient mechanisms to assist with aquatic hunting, including ultra-streamlined bodies, high intelligence, the ability to detect electrical fields and minute changes in water pressure, great hearing, incredibly sharp vision, amazing sense of smell (Lemon sharks can even detect tuna oil at a concentration of just one part per 25 million), and the topic of today- many rows of razor sharp teeth, including the ability to rapidly replace them. But are sharks actually able to grow an unlimited number of teeth throughout their lives?

While sharks aren’t exactly the ruthless predators most Hollywood features make them out to be (see: Do Sharks Really Not Like How Humans Taste?), they do possess a number of frighteningly efficient mechanisms to assist with aquatic hunting, including ultra-streamlined bodies, high intelligence, the ability to detect electrical fields and minute changes in water pressure, great hearing, incredibly sharp vision, amazing sense of smell (Lemon sharks can even detect tuna oil at a concentration of just one part per 25 million), and the topic of today- many rows of razor sharp teeth, including the ability to rapidly replace them. But are sharks actually able to grow an unlimited number of teeth throughout their lives?

Yep. In fact, while the number varies wildly based on things like type of shark and lifespan, it’s not out of the question for a single shark to grow as many as 30,000-50,000 teeth in its lifetime!

This might have you wondering what the process is on how exactly sharks replace missing teeth?

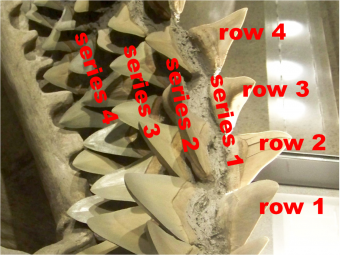

In a nutshell, all sharks have multiple series and rows of teeth. The number varies between type of shark, but most have between 5 and 15 series of teeth (counted from front to back) in their mouths which themselves contain between 15 and 25 rows of teeth (counted along the jawline). (As an example of how this can vary, the bull shark possess an unbelievable 50 rows and 7 series of teeth, giving it somewhere in the vicinity of 350 frightening teeth at any given time.) These teeth are arranged in such a way that the frontmost series will always house the largest teeth with the series behind it holding slightly smaller teeth and behind that holding smaller ones still, and so on until we get back to the rear series which are the most recently formed.

In a nutshell, all sharks have multiple series and rows of teeth. The number varies between type of shark, but most have between 5 and 15 series of teeth (counted from front to back) in their mouths which themselves contain between 15 and 25 rows of teeth (counted along the jawline). (As an example of how this can vary, the bull shark possess an unbelievable 50 rows and 7 series of teeth, giving it somewhere in the vicinity of 350 frightening teeth at any given time.) These teeth are arranged in such a way that the frontmost series will always house the largest teeth with the series behind it holding slightly smaller teeth and behind that holding smaller ones still, and so on until we get back to the rear series which are the most recently formed.

These front teeth are referred to as the shark’s “working teeth” and are the ones primarily used for biting, tearing flesh and all of the other things a shark is thinking about doing when it’s swimming around below your legs as you dangle them in the ocean… This isn’t to say that the second, third or even the teeth located towards the back of a shark’s mouth aren’t used when a shark is devouring something like your lower half, it’s just that the front series of teeth are typically subjected to the most stress when this occurs. (Note: In truth, only about a dozen people per year are killed by sharks vs. approximately 20-30 million sharks per year killed by humans according to the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Department of Ichthyology. Who’s the apex predator now sharky?)

Given shark teeth are not deeply rooted like human teeth and given the animal’s incredible biting power, shark lose teeth pretty frequently when eating, usually front ones. Not only that, but they also naturally shed teeth throughout their lives, with the front teeth being fully replaced approximately every few weeks. (This rate varies by type of shark, age, and even the temperature of the water- younger sharks typically replace teeth faster and, at least in some types of sharks, colder temperatures help them hang on to their teeth longer.) This means that the teeth in a shark’s mouth are nearly always in pristine condition and quite sharp, as they typically never get the chance to be dulled or worn over time before being shed or broken off.

Whenever a shark loses a tooth, the tooth directly behind it will begin to be pushed forward into the area left by the old tooth, all the while growing to the size of the tooth it is replacing. At the same time, the tooth behind that will do the same thing and so will every other tooth until the shark once again has a full set of teeth- more or less a “conveyor belt” of death.

And if you’re wondering whether or not losing teeth via them breaking off when they bite something hurts sharks, this isn’t clear. Shark teeth do have a certain amount of flex (in great whites approximately 15 degrees of flex) which they can sense, using this fact to help “feel” things, not unlike how a human might touch something to feel its texture. But as for pain in over-flexing to the point of loss of a tooth, observations of sharks in the wild and captivity seem to indicate that, if there is any pain involved, it is only minor discomfort at most.

Given how critical it is for sharks to have a good set of chompers and how easily teeth are broken off, it will likely not surprise you that this replacement process happens quite quickly. As for an exact time-frame, this varies and can be influenced by a number of factors including the size, species and age of the shark, how recently the tooth replacing their missing tooth was itself replaced and the shark’s overall health. But for a ballpark figure, this process can take anywhere from between a single day to a few weeks. However, even in the event that replacing the tooth does take weeks, the smaller teeth are still useful, meaning the loss of even several teeth in the first series is highly unlikely to negatively impact the shark in question.

So to sum up, as far as experts are aware, there is no upper limit on the amount of teeth a given shark can produce in a lifetime; as long as it stays healthy, a shark will continue to grow new teeth until the day it dies.

As a side-effect of all this, the ocean floor is covered in many trillions of shark teeth, which is one of the reasons we know so much about shark evolution. You see, as with most teeth, because shark teeth are primarily made of a hard, calcified tissue known as dentin (for reference elephant tusks are primarily made of dentin as well) surrounded by an even harder layer of enamel, their teeth don’t typically decompose. This, combined with how (relatively) quickly their teeth are fossilised by the sediments on the ocean floor, means we have a massive number of ancient shark teeth to study today. (And if you’re curious, see How Do Things Become Petrified?)

(As another interesting aside, a shark’s placoid scales are also made up largely of dentine and don’t grow in size once in place. So to accommodate this, as their bodies grow, they produce new teeth-like scales to more or less fill in the gaps.)

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Do Sharks Really Not Like How Humans Taste?

- How Fish Gills Work

- Can Fish Get Thirsty and Why Can’t Freshwater Fish Live in Saltwater and Vice Versa?

- Could Piranha Really Turn You Into a Skeleton in a Matter of Minutes?

- Why Fish Often Float Upside Down When They Die

Bonus Facts:

- Similar genes in sharks (and alligators) that allow them to grow infinite teeth also exist in humans, but we only take advantage of this once in adolescence before this system is more or less switched off and the needed epithelial cells are no longer generated. But it would seem at least theoretically possible that at some point we’ll figure out a way to more or less switch these genes back on, allowing humans who’ve lost teeth or otherwise have teeth that could really use replaced to do so naturally. (And if you’re wondering, alligators maintain two sets of teeth at any given time, with the adult tooth visible in the mouth, a small replacement tooth growing underneath for if the adult tooth is lost, and stem cells that can become replacement teeth when needed underlying it all- essentially a somewhat similar system as young humans have.)

- As to why sharks and alligators (among other animals) are thought to have this infinite teeth regeneration ability and humans don’t- these animals have ultra powerful bites, among other things contributing to the chances of them losing teeth; thus, such a system switching off would be disastrous unless they evolved better rooted teeth or the like, ensuring sharks and alligators who have this trait were more likely to survive and were able to develop even more powerful bites. For humans, while it’s handy to have a larger set of teeth to grow in once our jaws are big enough to accommodate them vs. keeping our original smaller set, it’s really not that big of a deal to lose the ability to continue to generate teeth after that. Our existing ones have evolved to be tough, deeply rooted, come with built in pain sensors should we bite down too hard on something and risk their structural integrity, and the loss of some, or even all, teeth presumably hasn’t been a major problem from a survival standpoint since humanity learned to use tools. And certainly even then is only terribly likely in many in twilight years when one has already had ample time to reproduce and potentially rear young.

- On some island nations, for example Hawaii, shark teeth frequently wash ashore or can be found in the shallows. Along with being used for decoration, in the past, the teeth were sometimes incorporated into weapons such a clubs or rudimentary swords. These weapons, despite their unrefined appearance, were deadly in the right hands thanks to the fact that shark teeth retain their sharpness, even after being shed, particularly if relatively freshly aquired.

- Hammerhead sharks can reproduce asexually. The first documented case of this happened on December 14, 2001 at the Henry Doorly Zoo in Nebraska where a female hammerhead shark, which was kept in isolation from males, miraculously gave birth to a pup. The pup was unfortunately killed by a stingray shortly thereafter, but testing showed that the pup was, in fact, a child of only its mother, though not a perfect clone, containing only half of its mother’s DNA. This made it the first documented case of a cartilaginous fish reproducing this way.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|