Why Did Old Timey Boxers All Pose For Photos the Same Way?

Jason H. asks: Why is it that every single old photo of a boxer shows them posing the same goofy way?

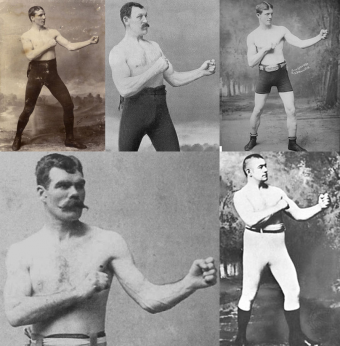

If you go and look up a photo of a boxer from the 19th century, it’s almost certain that the individual will be standing like the gentlemen pictured right. While it may look a little silly to modern fans of the sport, this was actually a very effective fighting stance for those wishing to win a 19th century boxing match.

If you go and look up a photo of a boxer from the 19th century, it’s almost certain that the individual will be standing like the gentlemen pictured right. While it may look a little silly to modern fans of the sport, this was actually a very effective fighting stance for those wishing to win a 19th century boxing match.

For anyone unfamiliar, the reason this old timey, once ubiquitous, “fisticuffs stance” is so mocked or derided by fans of the sport today is for the glaring weaknesses inherent to it, namely that the boxer stands with their hands low and their chin up- a great way to get your head pummeled.

While it’s certainly true that a person utilising the fisticuffs stance would be in trouble in a modern day boxing match, a modern boxer would likely be in just as much trouble sparring off against a pugilistic champ from the golden age of boxing, if they boxed by the rules of the period. As for why, most pertinent here is the fact that neither boxer would be wearing gloves in such a classic match.

As paradoxical as it’s going to sound, boxing without gloves is actually widely considered to be safer than boxing with them, among other reasons because bare knuckle boxers rarely punched one another in the head with full force, so the risk of brain injury or knockout was dramatically lower. You see, lacking protective hand gear, punching someone in the head with every ounce of your physical might is a great way to very seriously injury your hands, particularly when done repeatedly.

Combine this with the fact that many 19th century boxers sometimes competed multiple times per week and that there were no time limits for many old timey bouts (one match in 1893 even went 111 rounds, see Bonus Facts below), and you begin to see why protecting the head wasn’t as much of a concern as it is today. While blows to the head did happen, particularly if a clean shot to the cheek could be had, the head tended not to be the focus.

(This aversion to headshots is believed to be one of the reasons so many old timey pugilists were able to compete so frequently and keep boxing for upwards of three decades in some cases, all the while maintaining their mental faculties well into old age.)

So that explains why the stance doesn’t have the hands more directly protecting the head like today, but why the specific hand position of left arm out and right arm tucked? Among other benefits, this is partially linked to another, often overlooked rule of early boxing bouts. Prior to the Queensbury rules officially introduced in the 1860s and proliferating from there, the rules of specific prize fights between pugilists varied, but invariably allowed grappling. As an example of how things were before more civilised competitions, in 1713, Sir Thomas Parkyns described a typical boxing match as including eye-gouging, choking, punching, head-butting and other such street fighting tactics.

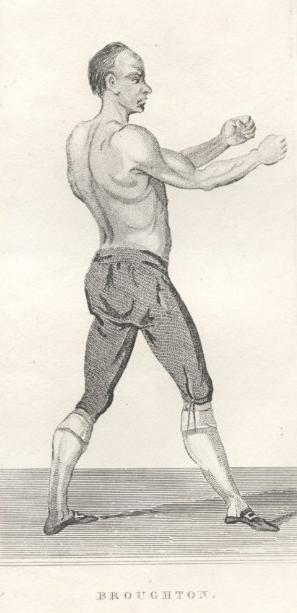

This all changed when Jack Broughton developed the first set of formalized rules for boxing in 1743. The impetus for these rules came, in part, from Broughton’s defeat of George Stevenson, who suffered severe injuries and died a few days after the pair’s fight. Saddened by the death of his competitor, Broughton wrote the “Broughton Rules” to minimize the harsher aspects of the sport, like forbidding striking below the belt, not allowing hitting a competitor when he was down and giving him 30 seconds to recover and continue the fight, lest he be declared the loser. However, one thing Broughton’s rules did allow was the aforementioned grappling.

As a result, the boxing stance of the era emphasized keeping distance between yourself and your opponent, usually with both arms outstretched. Later, thanks to an individual we’ll talk about shortly, it switched to just keeping your left hand outstretched. This not only made for a potential minor offensive weapon your opponent had to worry about if they tried to come in close, but also was great for teasing out and defending against jabs and glancing blows from a distance. The tucked right (dominant for most) hand being held close helped defend against counter hooks and body blows when your opponent managed to get past your left arm. And, of course, the arm was cocked and ready to deliver more powerful blows. Keeping both arms tucked would simply allow your opponent too easy grappling access to your main trunk.

As a result, the boxing stance of the era emphasized keeping distance between yourself and your opponent, usually with both arms outstretched. Later, thanks to an individual we’ll talk about shortly, it switched to just keeping your left hand outstretched. This not only made for a potential minor offensive weapon your opponent had to worry about if they tried to come in close, but also was great for teasing out and defending against jabs and glancing blows from a distance. The tucked right (dominant for most) hand being held close helped defend against counter hooks and body blows when your opponent managed to get past your left arm. And, of course, the arm was cocked and ready to deliver more powerful blows. Keeping both arms tucked would simply allow your opponent too easy grappling access to your main trunk.

As for how this stance became popularised, this appears to be in large part thanks to an 18th century prize fighter called Daniel Mendoza. Before Mendoza, boxing matches tended to consist of two men more or less beating on each other in any way possible until one of them couldn’t get up anymore. These matches were more of a show of manliness and brute strength than the subtle art that would soon develop. Investing too much effort in defending yourself or even taking the complete “coward’s” way out and attempting to full on duck and dodge regularly wasn’t something the fighters really did. That’s not to say they put no thought into defence- as mentioned, keeping two arms outstretched was a classic stance of the period- it’s just that Mendoza took it to a whole new level.

His style developed out of necessity, Mendoza stood at only 5 ft. 7 in. (1.7 m) and about 160 pounds (73 kg) in a time when boxing was invariably dominated by the biggest and strongest men. But thanks to his “scientific” approach to boxing, Mendoza in turn dominated opponents with relentlessly sneaky offence combined with heavy emphasis on not just blocking blows, but slip and dodging them as well- essentially he floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee before it was cool.

His style developed out of necessity, Mendoza stood at only 5 ft. 7 in. (1.7 m) and about 160 pounds (73 kg) in a time when boxing was invariably dominated by the biggest and strongest men. But thanks to his “scientific” approach to boxing, Mendoza in turn dominated opponents with relentlessly sneaky offence combined with heavy emphasis on not just blocking blows, but slip and dodging them as well- essentially he floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee before it was cool.

While many accused him of being a coward for fighting this way, the results spoke for themselves; the little man, despite being much smaller than most of his opponents, became the Heavyweight Champion of England from 1792 to 1795- a true to life David vs. Goliath personification, making Mendoza exceptionally popular with the masses.

Mendoza was only finally defeated owing to his hair. In a match against John Jackson who was a full 4 inches taller and over 40 pounds heavier than Mendoza, Jackson managed to grab Mendoza by the hair and then proceeded to, ironically enough, continually punch him in the face with his free hand while the other kept a firm grip on the hair, ultimately knocking Mendoza out.

Nevertheless, Mendoza’s famed career culminated in him quite literally writing the book on “scientific” boxing technique. Published in 1792, The Art of Boxing touts the benefits of counter punching and a solid defence:

It must be an invariable rule to stop or parry your adversary’s right with your left, and his left with your right; and both in striking and parrying, always keep your stomach guarded, by barring it with your right or left fore-arm.

This is advice it would seem most every notable boxer after Mendoza’s time took to heart, as most boxers pictured after his reign invariably were shown holding one hand protectively close to their body and the other outstretched. Prior to this, as previously mentioned, champions such as Jack Broughton were idealised in drawings holding both hands away from the body, leaving the abdomen somewhat exposed.

This is advice it would seem most every notable boxer after Mendoza’s time took to heart, as most boxers pictured after his reign invariably were shown holding one hand protectively close to their body and the other outstretched. Prior to this, as previously mentioned, champions such as Jack Broughton were idealised in drawings holding both hands away from the body, leaving the abdomen somewhat exposed.

With the introduction of gloves in actual matches thanks largely to the Queensberry rules (before this gloves were mostly just used in training), boxing forms evolved, with the emphasis of the modern stance being protecting the head from the gloved fist.

Old traditions die hard, however, and for a period in the early 20th century, despite that bare knuckled bouts had been phased out, boxers continued to pose like old timey prize fighters for publicity stills, even though they now fought using a different style.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why are Boxing Rings Called Rings When They Are Square?

- The Human Windmill: The Best Boxer You’ve Probably Never Heard Of

- Does Sex Before An Athletic Event Really Hinder Performance?

- What are Smelling Salts?

- Hulk Hogan, George Foreman, and a Lean Mean Fat-Reducing Machine

Bonus Facts:

- The longest known boxing fight in history took place in New Orleans on Apr. 6, 1893, between Andy Bowen and Jack Burke. The fight was for the lightweight world title and lasted 111 rounds! After seven hours of brutal fighting, when the bell sounded for the 111th round, both fighters – dazed and exhausted- refused to come out of their corners and the referee ruled the bout as a no contest. So yes, after 111 rounds of using their bodies as punching bags, the contest ended in a tie.

- Jack Marles, a London dentist, introduced the first mouth guard for boxers in 1902. At first, the safety measure to protect a fighter’s teeth and mouth was used only in training sessions. It wasn’t until 1913 that the first boxer wore one in an official fight. It didn’t take long for mouthpieces to catch on among boxing to reduce injuries to the teeth and mouth.

- In the 1999 film “The Hurricane,” starring Denzel Washington, the 1964 world championship bout between Rubin Carter and the former world middleweight champion, Joey Giardello, is portrayed such that Carter clearly won, but the racist judges ruled that Giardello won the match, becoming the world champion. However, the truth was that Giardello, a member of both the International Boxing Hall of Fame and World Boxing Hall of Fame, dominated that fight and won fair and square. In a CNN interview shortly after the film’s release, Carter himself discussed this and confirmed that Giardello was the rightful victor of the match, despite what was shown in the movie. This creative liberty taken by the film makers resulted in Giardello suing them. They ultimately settled out-of-court with Giardello for an undisclosed sum.

- Why Boxing Rings are Square

- The Art of Boxing

- Art of Boxing and Science of Self-defense: Together with a Manual of Training

- Daniel Mendoza – Jewish Sports Hall of Fame

- The Development of Boxing Strategies, Styles and Techniques During the Gloved Era to Present–Part 1

- Why Bare-Knuckle Fighting May Be Safer Than Boxing

- London Prize Ring rules

- Daniel Mendoza

- Boxing Style and Technique

- William Thompson

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

The 111 rounds bout really got my attention. After some research I found another few curiosities about it:

Burke broke both of his hands (some sources say all the bones in both of them).

They had lost nearly 10 pounds each from the effort.

110th round ended without a punch thrown which made the referee to declare it a “no contest” (which in fact made it a 110 rounds bout, not 111).

Bowen fought again just two months later, this time for 85 rounds.

Those pictures of stances that you start off your megillah, that every boxing enthusiast knows backwards and forwards….You make me laugh. They had to stand still because they were PHOTOGRAPHS. They didn’t “square up” like that in a fight…Use your common sense-if you have any. I hope you weren’t getting paid for the article…taking money under false pretenses might be, only might,… thought.

Tere are some surviving videos as well as verbal descriptions of matches from 1897 Corbett-Fitzsimmons on. And they were already set i their styles for years before.

Jack Johnson who was fighting in 1902, moved around the ring like Ali, and had every punch known to modern boxers and more than a few which are not known to them. One of your pictures is not a pre 1900 one at all but of a well known boxer who had over 200 fights before he was accidentally killed on a motor bike. I have that same picture. He was a model as a man and a fighter. from around 1918 to about 1932 or 33 , I’m speaking generally, can’t bother to look him up.

Talking about Mendoza, whose biography I have, before him, boxing included wrestling, quarterstaff work, swords and etc. They gradually dropped out to become exclusively fistic battles. ,

Did you actually WATCH that Corbett-Fitzsimmons video? Fitzsimmons uses exact same stance as described in the article, with head pulled back. There is a video of Jeffries-Fitzsimmons fight few years later, showing same thing.

It is true that by turn of the century, classic English stance was already getting obsolete. None of Johnson, Jeffries, Burns used it.

I stand like this whenever someone wants to start a fight with me. This causes the aggressor to begin laughing hysterically and I slip away while they are distracted.