That Time Mozart Pirated a Forbidden Piece of Music from the Catholic Church from Memory

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is known for many things, few of which we care to cover on this site because you probably already know all about them. Instead, we prefer to cover things that you likely didn’t know, like that the alphabet song was based on a tune by Mozart, or covering his extremely adult themed works that included a bit of an obsession with all things scatological, and the significantly more family friendly subject of today- that time Mozart pirated a cherished choral arrangement from the Vatican, reportedly all from memory.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart is known for many things, few of which we care to cover on this site because you probably already know all about them. Instead, we prefer to cover things that you likely didn’t know, like that the alphabet song was based on a tune by Mozart, or covering his extremely adult themed works that included a bit of an obsession with all things scatological, and the significantly more family friendly subject of today- that time Mozart pirated a cherished choral arrangement from the Vatican, reportedly all from memory.

That piece was Miserere mei, Deus (literally, “Have mercy on me, O God”), which was based on Psalm 51 and composed by Catholic priest Gregorio Allegri sometime in the 1630s.

Although today Miserere is regarded as one of the most popular and oft recorded arrangements of the late Renaissance era, for many years, due to papal decree, if one wanted to hear it, one had to go to the Vatican. The punishment for ignoring the ban on copying this music is widely stated by many a reputable source (as well as Mozart’s dad, Leopold) to be excommunication from the Catholic church. (Although I couldn’t find any primary documents that back Pope Urban VIII, or any other Pope, ever making such an official decree, and various pirated versions of the music are known to have existed during the moratorium without anyone seeming to have been excommunicated.) Nevertheless, there was indeed a ban on copying the music that lasted for almost a century and a half.

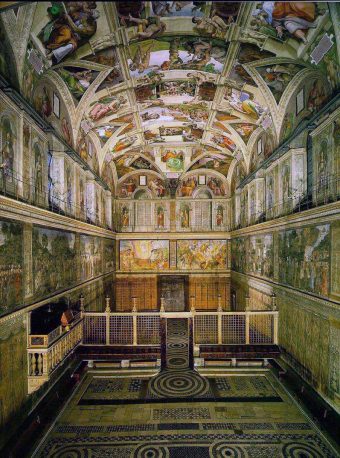

To add to the mystique surrounding the piece, it was only allowed to be performed publicly on two specific days during the Holy Week (the week before Easter)- Holy Wednesday and Good Friday. (And if you’re curious, see: Why Determining Easter’s Date is So Confusing) All this, combined with the superior acoustics of the Sistine Chapel and the unparalleled talent of the Papal Choir resulted in the piece becoming an almost mythical entity, with people travelling from across the globe to hear it performed in all its glory.

Though the Vatican refused for many years to ever release a copy of the sheet music for the piece, by the mid eighteenth century the Church had been cajoled into gifting three copies to prominent individuals. These individuals were the King of Portugal, famed composer and Catholic friar Giovanni Battista Martini, and Emperor Leopold I.

In regards to Emperor Leopold, he seems to have heard the piece on a visit to the Vatican sometime in the late 1600s, becoming enamoured with it. Leopold used his influence to convince the Pope to give him a copy of the sheet music. He then summoned the finest singers he had at his command and arranged for a performance of the piece to be held in the Imperial Chapel in Vienna. By all accounts, the resulting performance was lacklustre and dull. This supposedly resulted in the Emperor believing he’d been cheated and given an inferior copy of the music, sending a courier to the Vatican to explain to the Pope what had happened. Apparently upset himself over his orders not being followed, the Pope subsequently is said to have dismissed the Maestro di Cappella who’d provided the music.

As it turns out, Leopold had indeed been sent a genuine copy of the sheet music. However, over the years the Papal Choir had added many embellishments to the original work that were not reflected in the sheet music, nor were they seemingly ever written down. The story goes that the Maestro di Cappella eventually got his job back when this was explained to the Pope. Whether that oft’ told story is perfectly accurate or not, Emperor Leopold would later enshrine the copy of Miserere he’d been given in the Vienna Imperial Library.

This all brings us to 1770 when a 14-year-old Mozart was touring around Italy with his father.

After arriving in Rome, Mozart attended the Holy Wednesday Tenebrae, during which he heard Miserere in full. Later that day, Mozart, who was already considered a musical prodigy at this point, transcribed the entire 15 or so minute piece from memory. He is also rumoured to have attended the Good Friday performance later that week to hear it again, helping to improve upon his unauthorised copy. (Popular myth states that he smuggled his copy into the performance in his hat and corrected it on the spot.)

Despite knowing that copying the piece was taboo, Mozart’s father, Leopold, was reportedly impressed that his son had managed to transcribe the song from memory, writing in a letter to his wife dated April 14, 1770:

You have often heard of the famous Miserere in Rome, which is so greatly prized that the performers are forbidden on pain of excommunication to take away a single part of it, copy it or to give it to anyone. But we have it already. Wolfgang has written it down and we would have sent it to Salzburg in this letter, if it were not necessary for us to be there to perform it. But the manner of performance contributes more to its effect than the composition itself. Moreover, as it is one of the secrets of Rome, we do not wish to let it fall into other hands.

Unlike the other, authorized copies of the piece that existed at the time, Mozart’s supposedly included the multitude of flourishes and ornamental embellishments employed by the choir that were of fundamental importance to the arrangement, but, as previously stated, not in the original music by Allegri.

All this said, while that is the widely reported story, it should be noted here that it isn’t actually clear from evidence at hand how accurate Mozart’s copy of the piece was, as it has unfortunately been lost to history, and going off a boasting father’s account is somewhat suspect. However, for those who support the idea that Mozart made a perfect copy, it is noted that Miserere is an amazingly repetitive piece, with the gist of most of the arrangement coming in the first few minutes.

It’s also often stated that a short while after transcribing Miserere, Mozart was at a party with his father when the topic of the tune came up in conversation, at which point Leopold boasted to the guests that his son transcribed the legendary piece from memory, prompting some amount of skepticism from the attendees. However, in attendance at said party was a musician named Christoferi, who’d actually sung it while a member of the Papal Choir. After looking over the copy made by Mozart, he supposedly confirmed that it was a faithful reproduction.

Whether that party anecdote actually happened is as difficult to determine as many other details of this tale. But what is 100% verifiable fact is that news of this supposedly extremely accurate unauthorized copy of Miserere eventually reached Pope Clement XIV (perhaps even via Leopold Mozart himself spilling the beans to the Pope in a letter). The Pope then summoned the young composer to Rome while Mozart was travelling through Naples. However, rather than being upset or excommunicating Mozart, the Pope was impressed by the young composer’s musical ability and initiative and instead awarded him the Chivalric Order of the Golden Spur– essentially a Papal knighthood. This, perhaps, gives credence to the notion that Mozart’s copy of the work must have been reasonably accurate, as presumably the Pope would have checked with his Maestro di Cappella concerning Mozart’s transcription before awarding such an honour.

This knighthood was something Mozart seems to have been extremely proud of, including frequently wearing the cross medal that came with being knighted. He also took to signing his name Chevalier de Mozart. However, in a letter to his father dated October of 1777, the 21 year old Mozart reveals that, during a concert in which various nobles were in attendance, Mozart wore the mark of his papal knighthood and the nobles mocked him for it, after which he seems to have ceased wearing it and further stopped signing his name with the title.

In any event, impressed by Mozart and no doubt realising, both based on Mozart’s transcription of the work and the others that existed at the time, that the cat was out of the bag (or perhaps simply not caring as his predecessors had), Pope Clement XIV got rid of the ban concerning copies of the music for Miserere, ostensibly making it available to the masses. However, due to the abbellimenti that the Papal Choir employed when they performed the piece, compared to what the stock music said, for almost a century more the true Vatican version of the song remained something you could only hear at the Vatican. It wouldn’t be until 1840 when a Catholic priest by the name of Pietro Alfieri published the embellished version of Miserere that the world finally had what is considered to be an accurate sheet music representation of the Chapel Choir version of song.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Was Beethoven Really Deaf When He Wrote All His Music?

- What Killed Mozart

- Will Listening to Mozart Really Make You Smarter?

- A Violinist and the Devil

- When Did People First Start Clapping to Show Appreciation?

Bonus Facts:

- It is commonly said that Mozart gave (or sold) his transcription of Miserere to British music historian Dr. Charles Burney, who published it in 1771 directly after his own tour through Italy that more or less coincided with Mozart’s. However, the direct evidence that Burney’s version came from Mozart is scant. And if Burney’s version did come from Mozart, it is noteworthy that this version lacked the ornamentation that made the Papal Choir’s performance so famous, perhaps implying Mozart’s transcription wasn’t quite as accurate as is commonly stated. Although, again, it isn’t actually clear Burney’s version was copied from Mozart. In fact, precisely because Burney’s Miserere doesn’t include any of the abbellimeni, that would seem to imply it would not have come from a version transcribed from a performance by the Chapel Choir.

- The speculative connection that Burney’s version was from Mozart partially comes from the fact that Burney is known to have encountered Mozart while he was on his Grand Tour. But it should also be noted that Burney additionally met with Padre Giovanni Martini, who, as previously mentioned, was one of the three individuals that had an authorised copy of the Miserere- a copy lacking the choir’s embellishments on the original work by Allegri… like Burney’s version… The speculation that Burney based his version off something Mozart wrote vs perhaps getting to look over Martini’s copy is primarily based on further speculation that Martini would not have allowed Burney to copy the work or look over it too closely due to the moratorium on copying it that was still in place at the time.

- Beyond Burney potentially having gotten a good look at Martini’s copy, given Mozart’s first meeting with Martini seems to have come shortly before he made his own transcription of Miserere, it’s even possible Mozart got a chance to look over the authorised copy of the music before he heard and subsequently transcribed his own copy of it.

- In letters that were, until recently, housed in the closely guarded Vatican archives, it’s noted that the Pope was made aware of Mozart’s actions by an unnamed individual who had “petitioned in his name”. While this individual isn’t named in any document available to us, as previously alluded to, historians believe that it was likely Leopold who wrote to the Pope about Mozart’s transcription.

- Vatican reveals Wolfgang Mozart’s papal honour

- Choice Biography: Comprising an Entertaining and Instructive Account of Persons of Both Sexes and All Nations Eminent for Genius Learning Public Spirit Courage and Virtue

- Gregorio Allegri

- Allegri’s Miserere – From Sistine Chapel Captivity to Immortal Life

- The Life of Mozart: Including His Correspondence

- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: A Biography

- Miserere

- Gregorio Allegri

- Charles Burney

- Miserere and Mozart

- Sistine Chapel Image Source

- Mozart vs the Pope

- The Truth Behind Mozart and Miserere

- The Story of Miserere

- Miserere

- Allegri Miserere

- Teaching the Bible Through Popular Culture and Arts

- The Writing on the Wall

- Miserere

- Miserere

- Psalm 51

- Psalm 51

- Allegri Miserere

- Giovanni Battista Martini

- Pietro Alfieri

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Great article. Even if it all was fake, it still would be a great reading ! Thanks.

Thank you very much for this great article.

Just want to point out that being musically trained myself, I could, as many other competent musicians, transcribe from memory first few minutes of the music. Given Mozart, as widely considered as a musical prodigy, it is not a stretch for him to transcribe the entire piece from his memory upon first time hearing the music.