Forgotten History: The First Movie and the Scientific Question It Sought to Answer

The first films were little more than what we would consider short clips, a boxer throwing a single punch or train arriving at a station– the type of scenes that today you might only see in the form of animated gifs. While popular perception is that movies got their start around the early twentieth century, the real seed that grew into the film industry came a few decades before that in Eadweard Muybridge’s truly revolutionary 1878 “Horse in Motion.” While it and hundreds of subsequent similar works Muybridge filmed wowed audiences the world over, this first film was not created to entertain, but to answer a question.

The first films were little more than what we would consider short clips, a boxer throwing a single punch or train arriving at a station– the type of scenes that today you might only see in the form of animated gifs. While popular perception is that movies got their start around the early twentieth century, the real seed that grew into the film industry came a few decades before that in Eadweard Muybridge’s truly revolutionary 1878 “Horse in Motion.” While it and hundreds of subsequent similar works Muybridge filmed wowed audiences the world over, this first film was not created to entertain, but to answer a question.

For centuries, artists, horse enthusiasts and scientists alike had wondered: Do all four of a horse’s hooves leave the ground in mid gallop? While this might seem silly and obvious to us today, at the time it was not so. In fact, if you look at artists’ depictions of horses galloping throughout history up to Muybridge’s “Horse in Motion,” they almost universally depict the horse in gallop incorrectly.

The problem, of course, was that this question could not be answered by the naked eye. And leading up to the momentous “Horse in Motion,” photographic technology of the day wasn’t up to the task of clearly capturing a horse galloping.

Enter Leland Stanford, who wanted to answer this question and, in the process, learn as much as possible about how horses run in order to potentially improve the performance of his race horses.

For a little background on the man, while today many have only heard of him because of the University he helped found (in homage to his son who died at 16), by today’s standards, Leland Stanford was somewhat corrupt. He initially made his fortune by selling mining equipment to those who came west for the California Gold Rush. He then invested a significant portion of this money into the California Central Pacific Railroad, becoming one of the “Big Four” to financially spur the success of the iconic railway. At the same time (and perhaps because of it), he was elected California’s governor. Using the office to enrich himself and his fellow investors further, he secured massive state investment and land grants for the railroad project. He became ludicrously wealthy (at his peak having a net worth of about $1.5 billion in today’s dollars), owned several mansions, vineyards and a racetrack in Palo Alto.

Speaking of this race track, after the completion of the railroad, horses became Stanford’s obsession. According to George T. Clark’s biography Leland Stanford, it was actually Stanford’s doctor’s orders that he take on supposedly stress free hobbies like horse rearing and racing. Because he apparently couldn’t do anything half-speed, Stanford wanted to revolutionize how trainers worked with racing horses. In order to do this, he realized he needed to figure out how horses ran – in the process answering the age old question. So, he turned to the best and most innovator photographer in San Francisco, Eadweard Muybridge.

Born in England in 1830, Muybridge moved to the United States and became a bookseller around 1852. Ultimately ending up in California, he was moderately successful at this venture and by the age of 30 decided he was ready for something else. He announced in the paper in 1860:

I have this day sold to my brother Thomas S. Muybridge my entire stock of books, engravings, etc. I shall leave for New York, London, Berlin, Paris, Rome, and Vienna, etc…

However, on his way to start his grand adventure, a fateful stagecoach crash in Texas resulted in Muybridge being ejected from the coach, at which point he smacked his head against a rock, causing severe brain trauma. When he awoke in a hospital some 150 miles away, he noted that, “each eye formed an individual impression so that looking at you, for instance, I could see another man sitting by your side.”

After several months, he recovered enough to return to England, but did not go on the grand tour he’d previously planned, instead spending the next six years in his native land.

While the accident may have left him with permanent brain damage, it also set the stage for the career that would make him world famous. You see, at some point during his lengthy recovery period, according to Muybridge, one of his physicians suggested he take up the relatively new field of photography.

Fast forward to 1872 and Muybridge was one of the leading photographers in the world, being vaulted to that world-wide fame after shooting over 200 stunningly clear shots of Yosemite Valley in 1868. (An easy thing to do today, but in his time an amazing achievement; beyond being exceptionally difficult to capture such shots with any clarity due to long exposure times, this also required him to trek around the wilderness for several months carrying all the equipment he’d need to both take and develop the photos on the spot. Once a location was chosen, he’d then have to wait for just the right lighting and weather conditions that would allow him to take the expansive shots without blurring.)

Wanting the best, as previously noted, Stanford approached Muybridge about helping him figure out how exactly a horse runs. Despite Stanford’s suggestion that they could do this by combining multiple real-time photos in succession, Muybridge declared the task impossible. The available technology of the day wouldn’t allow it; exposure times were typically on the order of 15-60 seconds, which was completely unsuitable for capturing any motion whatsoever.

Money talks, however, and Stanford was ultimately able to convince Muybridge to take on the project via offering him what ended up being more or less an open ended budget.

While the pair made significant progress on this front over the next two years, including managing to capture a very blurry image that seemed to show a horse galloping with all four legs in the air, in 1874 the project was interrupted because Muybridge was arrested for murder- a crime he happily confessed to.

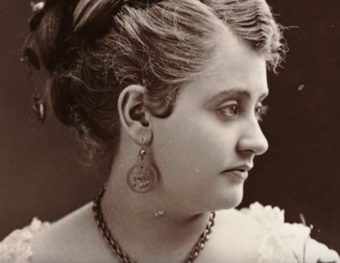

You see, two years earlier he married the 21-year-old (and 20 years his junior) Flora Stone. (When he originally met Stone, she was already married, with Muybridge paying for her divorce.)

You see, two years earlier he married the 21-year-old (and 20 years his junior) Flora Stone. (When he originally met Stone, she was already married, with Muybridge paying for her divorce.)

Back to 1874, on April 15th of that year she bore a son, Floredo Helios Muybridge. Not long after the birth of the child, Muybridge went to pay the midwife who delivered the boy, Susan Smith. While there, Muybridge discovered a photograph of his son. On the back, it said “Little Harry” in his wife’s handwriting…

When Muybridge saw this, he went ballistic. Under extreme duress, the midwife confessed to Muybridge that Flora and one Major Harry Larkyns were having an affair.

The midwife later recounted what happened next, “When I told Muybridge of the affair, he cried like a baby…” He then asked her, “Who’s baby is that, mine or Larkyns?” She replied, “I do not know.” She then told him she had seen his wife “on the bed with her clothes down to her waist and Larkyns sat on the bedside…”

Muybridge did not take the news well. “In great agony of mind, he wandered about. My opinion is when he left me he was insane.”

Directly after leaving the midwife, Muybridge went home and collected his revolver. He then took a train and then a horse and carriage to Larkyns’ home.

Arriving several hours after learning of the affair, Muybridge knocked on the door. According to the February 4, 1875 edition of the San Francisco Chronicle, when Larkyns answered the door, Muybridge said, “I am Muybridge and this is a message from my wife,” at which point he pulled out his gun and shot Larkyns in the chest, killing him.

Muybridge was subsequently arrested and, a few months later, put on trial for murder.

At no point did he deny killing Larkyns, nor did he himself claim he had been driven insane when he killed him. Quite the contrary, in fact; he felt he was justified in the act. In an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle while in prison, Muybridge described his relationships and motivations,

We never had any trouble to speak of. We sometimes had little disputes about money matters, but they were not serious. I was always a man of very simple tastes and few wants, and I did not spend much money. What I had left over after paying my little expenses, I gave to her, but she was always wanting more. I could never see that she had bought anything with it to speak of or imagine what she did with it. We sometimes had little spats about money, but nothing serious…

I loved the woman with all my heart and soul. And the revelation of her infidelity was a cruel frustrating blow to me. Since the shooting I’ve been told many things to which I was previously blind. Friends whom I should have expected to inform me when they saw how I was being deceived have now told me all. I did not desire to see her again. They may ransack my record as much as they please, and I defy them to bring anything against me. I have no fear of the result. I feel that I was justified in what I did and that all right minded people would justify my action.

Of course, the law is the law and this sort of vigilantism tends to not hold up well when placed in the crucible of organized justice.

Luckily for Muybridge, the enormously wealthy Leland Stanford still wanted his question answered and needed Muybridge to do it. Thus, Stanford hired a team of lawyers to defend him, including C.H. King and W.W. Pendegast. They outlined their defense in their opening remarks on February 3, 1875:

We claim a verdict both on the ground of justifiable homicide and insanity. We shall prove that years ago, the prisoner was thrown from a stage, receiving a concussion of the brain, which turned his hair from black to gray in three days, and has never been the same since.

Ultimately the jury was not convinced that Muybridge had been insane, not the least of which because, as previously noted, in public comments he himself didn’t seem inclined towards the notion (though he never testified officially in the case). However, while the judge explicitly told the jury that killing a man for having an affair with one’s wife was by no means justifiable murder as far as the law was concerned, the jury didn’t agree. As noted in a contemporary report in the San Francisco Chronicle,

The jury discarded entirely the theory of insanity, and meeting the case on the bare issue left, acquitted the defended on the ground that he was justified in killing Larkyns for seducing his wife. This was directly contrary to the charge of the Judge, but the jury do not mince the matter, or attempt to excuse the verdict. They say that if their verdict was not in accord with the law of the books, it is with the law of human nature; that, in short, under similar circumstances they would have done as Muybridge did, and they could not conscientiously punish him for doing that they would have done themselves.

In the aftermath of the murder, Muybridge’s wife would divorce him, but she became ill and died about nine months after Muybridge killed her lover. As for Florado, with his mother no longer alive to care for him (and his supposed father dead at the hands of Muybridge), Muybridge unceremoniously put the poor boy in an orphanage, though he did provide for his financial needs. (It was later noted that the child grew up to slightly resemble Muybridge, perhaps indicating that he had indeed been his son and not Harry Larkyns’ as Muybridge and his wife had thought. Florado himself seems to have been inclined towards the notion as when he died at the age of 70 after being hit by a car, his tombstone stated: “Florado Helios Muybridge, Apr. 16, 1874 – Feb. 2, 1944, Son of photographer Eadweard James Muybridge”.)

Whatever the case, as for Muybridge, he traveled throughout South America for about a year before returning in 1876 to begin working with Stanford again. With Stanford’s ample resources in hand (the project ultimately costing about $50,000 or $1.14 million today), Muybridge invented a new rapid shutter mechanism and more sensitive chemicals allowing for quick, clear exposure of a galloping horse.

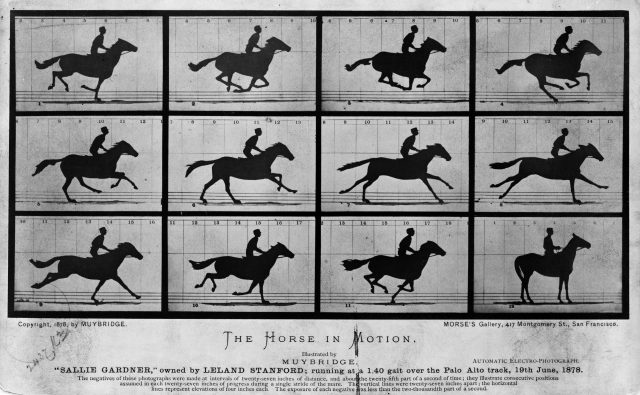

And so it was that after many failed experiments and ultimately some successful test runs that revealed the answer clearly, on June 19, 1878, Muybridge and Stanford invited the press to watch them officially capture something that would change the way we looked at the world.

On one side of the track was a white shed filled with a dozen cameras, each containing two lenses to make two separate exposures per camera (in case one didn’t come out right). On the other side was a white background to increase contrast. On the track itself was a series of 12 tripwires spaced approximately 20-21 inches (30 cm) apart, with each connected to the cameras’ shutter mechanism.

On one side of the track was a white shed filled with a dozen cameras, each containing two lenses to make two separate exposures per camera (in case one didn’t come out right). On the other side was a white background to increase contrast. On the track itself was a series of 12 tripwires spaced approximately 20-21 inches (30 cm) apart, with each connected to the cameras’ shutter mechanism.

Press surrounded the track. At the far end, master trainer Charles Marvin had the reins of one of Stanford’s race horses. With a gun blast, the horse took off. In less than half a second after she had reached the first trip-wire, the horse had tripped all 12 of them, setting up a succession of dropping shutters.

Time at this point was critical as the shots just taken had to be processed while the negatives were still moist, with only around 10-20 minutes to develop the 24 total plates after taking the shots. Once Muybridge had done this in his little mobile development studio, he put the pictures out for the gathered people to see.

It should be noted here that beyond the necessity to develop the shots right away, it was particularly critical for the press to see him do this. You see, some past test photos Muybridge had captured of a horse in full gallop had been largely dismissed by many in the press as forgeries, with some even going so far as to mock his supposed shots in cartoon caricatures. Many people simply refused to believe that it was actually possible to take a clear photo of a galloping horse. Thus, Muybridge wanted the journalists to see the horse galloping live and see him both take the shots of it and develop the photos in front of them so there would be no doubt of their accuracy and his accomplishment.

As for the pictures themselves, they were stunningly clear, with one witness to the event noting you could even see “the threadlike tip of Mr. Marvin’s whip… in each negative.”

Ultimately rough woodcuttings were made so that the photos could be transferred into newspapers for the public to see, with the following result: What was revealed in the succession of photo proofs is that, yes, horses did basically “fly” through the air when galloping, as, at one point, all four of their hooves did leave the ground. What’s more, this happened when their hooves were pointed inward as opposed to outward like most speculated and what the majority of artists up to this point had portrayed when showing horses galloping.

What was revealed in the succession of photo proofs is that, yes, horses did basically “fly” through the air when galloping, as, at one point, all four of their hooves did leave the ground. What’s more, this happened when their hooves were pointed inward as opposed to outward like most speculated and what the majority of artists up to this point had portrayed when showing horses galloping.

Some famed artists of the day took the news well, even subsequently contacting Muybridge to help them make their future works depicting horses more accurate. However, as was noted in the press, Muybridge’s photos seemingly made a mockery of pretty much all past artworks depicting horses moving. So it’s perhaps not surprise that some artists, such as famed sculptor Auguste Rodin (best known today for his “The Thinker” sculpture), went the other way, noting, “It is the artist who is truthful and it is photography which lies, for in reality time does not stop.”

Needless to say, Muybridge and Stanford’s stunt was a rousing success. But this was just the beginning. Muybridge now had a way to film things in natural motion. He quickly improved the technology, including inventing an electromagnetic timer to control the shutters instead of trip-wires (allowing for a shutter speed of 1/1000th of a second). Beyond this, he invented what was more or less the first movie projector in his zoopraxiscope, showing the first film of “The Horse in Motion” in the fall of 1879 to Stanford and a select group. As one reported noted of this first movie screening, “Nothing was wanting but the clatter of hoofs upon the turf and the occasional breath of steam to make the spectator believe he had before him the flesh and blood steeds.”

There was a problem in all this though. Initially Stanford and Muybridge seemed the best of friends and happy to credit the other for their respective contributions in this revolution of art and science- Stanford provided the funds, focus, and staff, and Muybridge did the inventing and capturing of the historic images.

This mutual credit would all change, however, with the publishing of a book by one of Stanford’s friends, Dr. J.B.D. Stillman, titled The Horse in Motion, in 1882.

In it, the aptly named Stillman would show around 100 drawings copied from Muybridge’s photos, but without crediting Muybridge. In fact, Muybridge was only mentioned in passing in the book as an employee of Stanford’s. This was despite the fact that the book was explicitly “Executed and Published Under the Auspices of Leland Stanford” who knew well Muybridge’s real contributions.

Beyond being offended at credit not being given, this also cost Muybridge a prestigious job and a fair amount of his reputation, at least initially, in his homeland. After witnessing several such films Muybridge had subsequently made in a lecture he gave in Britain, the British Royal Society of Arts offered him a rather lucrative contract to film other animals and people in motion for academic study. But when the book came out with no real mention of Muybridge, the Royal Society retracted their offer, thinking Muybridge was lying about his contributions in the project.

Not only that, but they also accused him of being a plagiarist. An academic paper Muybridge was attempting to get published on the motion of horses mirrored on several points what was written in Stillman’s book, but with no credit given to Stillman. Of course, the fact was that the work by Muybridge had formed the bases for Dr. Stillman’s notes in the book, not the other way around as the Royal Society now assumed.

Muybridge was devastated, lamenting, “The doors of the Royal Society were thus closed against me and my promising career in London was brought to a disastrous close.”

Muybridge would go on to not only sue the publisher of the book, but Stanford himself, thinking Stanford was intentionally trying to downplay Muybridge’s contributions to take all the credit himself, as so many who financed inventors have done before.

Ultimately Muybridge lost the lawsuits, but by this time the University of Pennsylvania, who did not doubt Muybridge’s work, offered to fund him in filming everything from birds in flight to nude men and women doing various things like carrying buckets, going up and down stairs, hitting baseballs, rowing boats, dancing, etc. (You can see some of these short films here, here, and here.) The point of all this, at least as far as the University was concerned, was to study various complex body movements in slow motion.

As for Muybridge, while he publicly lauded the scientific merit of his work, he more revelled in the art of it all, and rightly recognized how his work would influence artists to come. Beyond the more obvious examples, with several famed paintings in the subsequent decades just putting their own spin on one of Muybridge’s stills, his books could be found on the desks of many of the early animators in Hollywood as they tried to accurately depict motion. On top of this, Muybridge’s idea of what is now sometimes called “bullet-time” has been popular throughout the history of cinema, perhaps best depicted today in the original Matrix film. Long before that film (and many others before and since) used the exact technique, however, Muybridge was first- setting up a series of cameras in a semi-circle around subjects, timed to take pictures as they moved. In one such case, a nude Muybridge can be seen swinging a pic-axe.

In the end, Muybridge, who viewed himself as an artist rather than a scientist, ultimately made his money using his new technology to aid science while hoping to influence art. However, within a couple decades, the likes of the Lumière brothers and Thomas Edison (the latter of which who would consult with Muybridge) would eclipse his work with their own versions of this new type of technology, advancing the field from something akin to short animated gifs to lengthy productions. This was an advancement Muybridge foresaw and more, describing the future of what would become cinema,

In the not too distant future, instruments will be constructed that will not only reproduce visible actions simultaneously with audible words, but an entire opera, with the gestures, facial expressions, and songs of the performers, with all the accompanying music, will be recorded and reproduced by an apparatus combining the principles of the zoopraxiscope and the phonograph, for the instruction and entertainment of an audience long after the original participants have passed away.

Despite his life’s work being largely in the public eye, beyond initially having his accomplishments somewhat usurped by Stanford and Stillman, Muybridge’s role as one of the father’s of film would be largely forgotten by popular history. To add insult to injury, after he died in 1904, even his own tombstone has his name misspelled, inscribed “Eadweard Maybridge”.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Who Invented the Internet?

- The Timely Death of Kodak Founder George Eastman

- How One of the Most Beautiful Women in 1940s’ Hollywood Helped Make Certain Wireless Technologies Possible

- The United States v. Paramount and How Movie Theater Concessions Got So Expensive

- A Brief History of the Movie Rating System

Bonus Fact:

- Stanford sunk a huge percentage of his fortune, about $40 million (a little over a billion dollars today), into creating the notable Leland Stanford Junior University (commonly called just “Stanford,” though it still officially retains its original name). As previously mentioned, this university was named after his son who contracted typhoid fever shortly before his 16th birthday. He ultimately died of the condition shortly thereafter in 1884.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Muybridge was also one of the great landscape photographers. He was one of the first to photograph Yosemite. He photographed landscapes from Canada to Central America.