From Track Scrub to Olympic Record Setter- Fosbury and His Flop

In the early 1960s, high school athlete Dick Fosbury probably never imagined that he would set the Olympic high jump record in 1968. The then teenager at Medford High School in Oregon participated in the high jump portion of track and field, but as a sophomore, he failed to clear the 1.5 meter height required to qualify for a number of high school track meets.

In the early 1960s, high school athlete Dick Fosbury probably never imagined that he would set the Olympic high jump record in 1968. The then teenager at Medford High School in Oregon participated in the high jump portion of track and field, but as a sophomore, he failed to clear the 1.5 meter height required to qualify for a number of high school track meets.

The standard high jump techniques of the day included such techniques as the straddle and the upright scissors method. In the former, the jumper takes off from the inner foot to pass over the bar with their face down and legs straddling it. While American high jumpers at the Olympics used the technique to earn themselves silver and gold medals, Fosbury could not coordinate his limbs and body just right to make it over the jump at any great height.

Thus, he began experimenting with another high jump method- the upright scissors technique. Jumpers using this method approach the bar at a thirty to fifty degree angle before taking off with the outside leg. The leg nearest the jump remains straight and swings over the bar, and the takeoff leg is swung up over the bar once the jumper crosses it. Jumpers often bend forward at the waist once their takeoff leg clears the ground to lower their center of gravity.

With neither of these methods working terribly well for him, Fosbury began experimenting with different jumping techniques, achieving greater heights than he could with the standard methods of the day. One such method became the Fosbury Flop.

When Fosbury developed this innovative backwards, headfirst leap, it was quite by accident. He later stated,

It was just simply intuition. It was not based on science or analysis or thought or design. It was all by instinct. It happened one day at a competition [in May of 1963 at the Rotary Invitation at Grants Pass, Oregon]. My mind was driving my body to work out the best way to get over the bar…. I can remember the coaches looking through the rule book that day to see if what I was doing was legal, which it was. I ran into that over the next couple of years in high-school competition: the opposing coaches checking the rules.

If you’re wondering why this method had not been long since discovered by other jumpers, going over the bar headfirst and backwards meant that Fosbury would be landing on his back, something that would not have been possible before his junior year. You see, high jumpers prior to the early 1960s landed on surfaces made up of sand, sawdust, or woodchips, meaning you at least needed to partially land on your feet or risk injury. To get around the injury problem, colleges in the United States began bundling up soft foam rubber inside mesh nets in the late 1950s. These bundles not only provided a softer landing zone, but they stood about three feet tall, making it so jumpers did not need to fall as far on the way down. Just prior to Fosbury’s junior year, his school replaced its old wood chip filled landing area with such soft padding, making his otherwise back breaking flop viable.

Despite his success with the method, Fosbury’s high school coach initially insisted he keep practicing the straddle technique, but stopped pestering him when he used the flop to break his high school’s high jump record, clearing six feet, three inches (1.91 meters) and then shortly thereafter clearing six feet, five and a half inches (1.969 meters) at a state competition.

Fosbury’s subsequent college track and field coach at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Berny Wagner, also tried to get him to abandon his flop, for the entirety of his freshman year having him practice the western roll technique (where the jumper lifts themselves into a horizontal position over the bar). However, Fosbury was allowed to continue using his own technique at competitions. Things change when, during his sophomore year in the very first meet of the season, Fosbury flopped his way to a new school record of 6 ft. 10 inches (2.08 meters). After that, Fosbury stated, “Berny came up to me and said, ‘That’s enough.’ That was the end of Plan A, on to Plan B. He would study what I was doing, film it, and even start to try to experiment and teach it to the younger jumpers.”

It was while he was in college that Fosbury’s jumping technique became known as the Fosbury Flop. Fosbury later explained how his method got its name:

To tell the truth, the first time that I was interviewed and asked ‘what do you call this?’ I used my engineering analytical side (Fosbury was a civil engineering major) and I referred to it as a ‘back lay-out’. It was not interesting, and the journalist didn’t even write it down. I noted this. The next time that I was interviewed, that’s when I said, ‘Well, at home in my town in Medford, Oregon, they call it the Fosbury Flop’ – and everyone wrote it down. I was the first person to call it that, but it came from a caption on a photo that said ‘Fosbury flops over bar’.

Before this, one newspaper noted in a caption showing one of Fosbury’s leaps, “World’s Laziest High Jumper.” Yet another described his jump noting that it looked like “a fish flopping in a boat.”

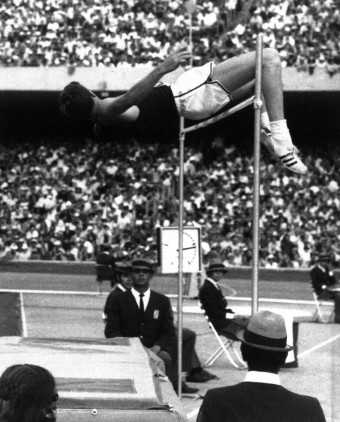

Nevertheless, five years after first flopping his way over a high jump bar, this former teenager who for a time couldn’t even qualify in certain high school meets, used his innovative method to get himself on the United States Olympic Team for the Mexico City Olympics in 1968. At that Olympics, he was one of only three jumpers to clear seven feet, two and a half inches (2.20 meters). With only three competitors left, he then managed to clear seven feet, three and a quarter inches (2.22 meters), along with his teammate, Ed Carruthers, while their Soviet Union competitor, Valentin Gavrilov, did not and ended up with a bronze medal.

The bar was then set to 2.24 meters, a height Fosbury cleared, setting a new Olympic record. Carruthers failed in all three tries, winning Fosbury the gold. Not satisfied, Fosbury then asked that they put the bar up to 2.29 meters (7 ft. 6.12 in.), just over the world record of 2.28 meters held by Valeriy Brumel. (Brumel had his career cut short in 1965 after a motorcycle accident resulted in serious injuries to his right foot. Even after a whopping 29 surgeries on it, his foot never recovered enough to allow him to jump competitively again, though he did attempt a brief comeback in 1970.) For Fosbury, beating Brumel’s mark was a leap too far and he failed on all three attempts to clear the bar.

The bar was then set to 2.24 meters, a height Fosbury cleared, setting a new Olympic record. Carruthers failed in all three tries, winning Fosbury the gold. Not satisfied, Fosbury then asked that they put the bar up to 2.29 meters (7 ft. 6.12 in.), just over the world record of 2.28 meters held by Valeriy Brumel. (Brumel had his career cut short in 1965 after a motorcycle accident resulted in serious injuries to his right foot. Even after a whopping 29 surgeries on it, his foot never recovered enough to allow him to jump competitively again, though he did attempt a brief comeback in 1970.) For Fosbury, beating Brumel’s mark was a leap too far and he failed on all three attempts to clear the bar.

Nevertheless, with Olympic gold in hand, the track and field world took notice of the Fosbury Flop. By the 1972 Olympics in Germany, twenty-eight of the forty high jumpers were using this method. The 1980 Olympics saw thirteen of its sixteen high jump finalists use it, and today, while other techniques can still be seen used by those warming up, when it comes to actual competition, some slight variation of the Fosbury Flop is the gold standard, and not a single person who’s used a different technique in the high jump has held the world record since 1980.

So why is the Fosbury Flop so much more effective than previous high jump techniques? Jumpers who use such techniques as the straddle method need their entire body to be above the bar when they reach the peak of the jump, meaning their center of gravity is also far above the bar.

While there are many different subtle variations on the flop, in general, at the apex of a jump, when their center of gravity is at its highest point, the jumper’s legs are still below the bar on one side while their head and torso are below on the other. If done optimally, and with sufficient flexibility, this means at no point does the jumper’s center of gravity need to go above the bar; in fact, at times it can be several inches below at its peak point, requiring significantly less leaping power to produce the same result as techniques that require the jumper’s center of gravity to go higher to clear the bar.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Heroic Death of Chariots of Fire’s Eric Liddell

- That Time an Olympic Rower Stopped to Let Some Ducks Swim By and Still Won the Gold Medal

- The Olympic Swimmer Who Had Never Been in a Pool Until a Few Months Before Competing in the Olympics

- Late for the Olympics: The Amazing Story of Kipchoge Keino

- How Did the Practice of Women Jumping Out of Giant Cakes Start?

- Fosbury Flop

- Fosbury flops to an Olympic record

- Fearless Fosbury Flops to Glory

- Floppin’ Heck!

- Dick Fosbury

- Olympics: Four decades later, we’re all still doing the Fosbury Flop

- This Day In Olympic History: Revolutionizing the High Jump

- Straddle technique

- Western roll

- Scissors jump

- Dick Fosbury – High jump men – athletics

- How High-Jumping Works

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Sure, but most of my back problems came from screwing up the flop and landing back first on the bar. Normally the bar just slides off, but in this case it I somehow pushed the bar forward, trapping it on the stand. I managed to hurt myself with the scissor method, too. Track and Field sucks.