This Day in History: October 15th- A Tale of Two Brothers, Hitler’s Right Hand Man and the One Who Opposed Him

This Day In History: October 15, 1946

This Day In History: October 15, 1946

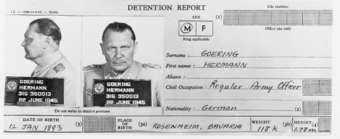

Hermann Göring was second only to Hitler in the hierarchy of the Third Reich. Commander of the Luftwaffe, acting Prime Minister of Prussia, President of the Reichstag, and Hitler’s designated successor – Göring’s Nazi resume was almost unparalleled.

Born in Bavaria in 1893, Göring was the son of a professional soldier and governor in West Africa. He followed his father’s footsteps and joined the military in 1912. He served in the Luftwaffe during World War I, and took over the command of “The Red Baron” Manfred von Richthofen’s old squadron. Although he won several awards for bravery and his numerous victories, Göring wasn’t popular with the other pilots, seemingly due to his arrogance.

After joining the fledgling Nazi party in 1922, Göring quickly became indispensable and was instrumental in the Nazi take-over of the German government. After Hitler became Chancellor, he appointed Göring as Prussian Minister of the Interior, Commissioner for Aviation, and Commander-in-Chief of the Prussian Police and Gestapo.

Göring never hesitated to enjoy the perks of his exalted position. He had a magnificent palace in Berlin as well as a luxurious hunting lodge named in honor of his late wife Carin, who died in 1931. He loved to play dress-up and would change his uniforms several times a day, proudly displaying all his medals. It was also joked among the press at the time that he probably bathed in his uniform.

Despite Göring’s own Godfather, Dr. Hermann Epenstein Ritter von Mauternburg, having been an exceptionally successful businessman of Jewish ancestry (and a man who his mother had a long lasting, open affair with, with his elderly father turning a blind eye to it and allowing his young wife to live with Epenstein), Göring was an advocate of the elimination of the Jews from the German economy and infamously ordered the “architect of the Holocaust” Reinhard Heydrich to “carry out all preparations with regard to . . . a general solution [Gesamtlosung] of the Jewish question in those territories of Europe which are under German influence …”

In 1939, Göring had serious reservations about his Luftwaffe being ready to face the Royal Air Force in battle, but Hitler pushed for the acceleration of the war plans and the war began anyway. At this point, Göring was at the peak of his power and popularity, and Hitler trusted him implicitly. But despite many early victories, the Germans couldn’t maintain their momentum.

As Germany’s fortunes grew dimmer, Göring’s standing with Hitler and the German people began to falter. At a time when most Germans were living hand-to-mouth, Göring’s lifestyle of extreme excess was no longer admired. His tendency to make bold claims to Hitler and not produce results didn’t hold him in good stead either.

The final straw was on April 23, 1945, when Berlin was close to falling. Göring, who had been declared by Hitler to be his successor if anything should happen to him, met with other officials and decided to take over as Hitler was trapped in Berlin. (Hitler would commit suicide just a week later.) When Göring officially requested Hitler approve the decision, Hitler was furious and charged Göring with treason. He then ordered Göring’s arrest, and stripped him of his rank and membership in the Nazi party. When Göring surrendered to the Allies in Austria on May 8, 1945, he did it, at least in theory, as a civilian.

To his apparent surprise, Göring was put on trial for war crimes at Nuremberg. During his trial, according to American intelligence officer and psychologist Captain Gustave Gilbert, when he interviewed him, Göring was “defensive and deflated and not very happy over the turn the trial was taking. He said that he had no control over the actions or the defense of the others, and that he had never been anti-Semitic himself, had not believed these atrocities, and that several Jews had offered to testify on his behalf.”

To his apparent surprise, Göring was put on trial for war crimes at Nuremberg. During his trial, according to American intelligence officer and psychologist Captain Gustave Gilbert, when he interviewed him, Göring was “defensive and deflated and not very happy over the turn the trial was taking. He said that he had no control over the actions or the defense of the others, and that he had never been anti-Semitic himself, had not believed these atrocities, and that several Jews had offered to testify on his behalf.”

Despite being “deflated,” Göring defended himself with great vigor and skill putting his vaunted 138 IQ to work (tested while in custody during the trial), occasionally outwitting the prosecution. After watching the films that documented the atrocities committed in the concentration camps, Göring claimed he was shocked at what was depicted and felt that the films had to have been faked somehow. Unsurprisingly given he was second only to Hitler in the Nazi party, nobody believed for a second that Göring hadn’t known about what was happening in those camps. In the end, Göring was found guilty on all four counts: conspiracy to wage war, crimes against peace, war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The judgement read,

There is nothing to be said in mitigation. For Göring was often, indeed almost always, the moving force, second only to his leader. He was the leading war aggressor, both as political and as military leader; he was the director of the slave labour programme and the creator of the oppressive programme against the Jews and other races, at home and abroad. All of these crimes he has frankly admitted. On some specific cases there may be conflict of testimony, but in terms of the broad outline, his own admissions are more than sufficiently wide to be conclusive of his guilt. His guilt is unique in its enormity. The record discloses no excuses for this man.

Hermann Göring was sentenced to die by hanging, but requested to die in what he viewed as a soldier’s death by firing squad; the court insisted he be executed like a common criminal.

Neither side got exactly what they wanted, but Göring still ended up just as dead when he ingested a cyanide tablet on this day in history, October 15, 1946, mere hours before his date with the hangman.

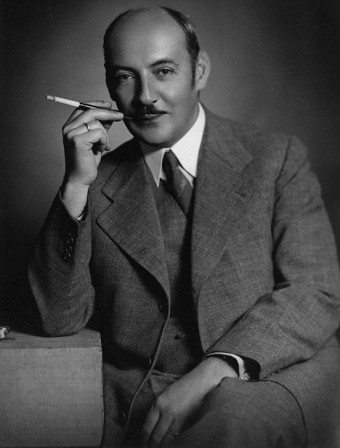

Unlike Hermann, his little brother, Albert, despised the Nazi party and did just about everything in his power to oppose them, frequently getting himself arrested, but getting off each time due to who his older brother was, and occasionally via direct intervention from Hermann.

Unlike Hermann, his little brother, Albert, despised the Nazi party and did just about everything in his power to oppose them, frequently getting himself arrested, but getting off each time due to who his older brother was, and occasionally via direct intervention from Hermann.

According to the book Thirty Four, by William Burke, Albert’s first known open act to help the Jews was a small one. While in Vienna, he happened upon a group of Jewish women who had a vicious mob around them and were being forced to scrub the streets. When he saw this, he simply walked up to one of the women, asked for a scrub brush from her, and knelt down and began scrubbing the street as well. This didn’t sit well with the officers who were overseeing the whole thing. But when they realized who Albert’s brother was, they quickly ordered the scrubbing to stop and the mob to disperse.

In a similar incident, this one which resulted in his own arrest, he came upon a small mob that was harassing an elderly Jewish woman, putting a sign around her neck that stated, “I am a Jewish sow.” Albert pushed his way through the crowd around her and helped the woman escape the little mob. In the process of doing so, he had to physically attack two members of the Gestapo, for which he was ultimately arrested. As before, once they realized who they’d arrested, he was set free.

More significantly, Albert is thought to have helped numerous Jewish people by helping fund an underground movement that helped Jews escape to freedom; he also forged his brother’s signature on several occasions to get Jews and others released from concentration camps and prison. Other times, he’d simply convince Hermann to sign an order to let certain people go, playing on his brother’s vanity and love for displaying his power.

In his most daring act, he drove up to a concentration camp and simply demanded he be given Jews for labor for the company Skoda Works, where Albert worked at the time. Normally, as he had no official papers for such a request, he would have been turned away. But because he was the brother of Hermann Göring, his request was granted. After loading his truck with as many Jews as he could, he drove them off to a remote area and let them go with instructions on their best route to freedom.

After that, though, the jig was up and an order was sent from Berlin to have him shot. He managed to escape to a safe house, however, and the war ended very soon after.

However, upon presenting himself to Allied soldiers, he was promptly arrested. Unlike his older brother, Albert was acquitted during the Nuremberg trials, though not before spending around a year and a half in prison, with no one believing him that he had actually spent the war actively working against the Nazis and helping as many people as he could escape their clutches.

In fact, when he first told his story after being arrested, Major Paul Kubala noted in Albert’s file, “The results of the interrogation of Albert Göring constitute as clever a piece of whitewash as we have ever seen.”

However, Albert finally did find someone willing to listen in Major Victor Parker. He had given Parker a list of 34 Jews he knew the names of that he had personally helped escape. Again, according to the book Thirty Four, by an extraordinary coincidence, one of the Jews on the list was Major Parker’s uncle. After verifying the claim with his uncle, he pursued the other names on the list who all testified in Albert’s defense and he was finally set free.

Unfortunately, after the war he found himself largely shunned due to his association with his brother and that few knew of Albert’s real activities during the war. As a result, he struggled to find work for the remainder of his life and ultimately became an alcoholic. As his health began to fail and death was imminent in 1966 (he was dying of pancreatic cancer), Albert decided to marry his housekeeper. This was not out of love, but simply because by doing so, she would then be entitled to his government pension, making sure she would be taken care of financially after her services as his housekeeper were no longer required. He died a week later in December of 1966.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Angel of Death: Josef Mengele

- The Man Who Personally Executed Over 7000 People in 28 Days, One at a Time

- Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen, a.k.a., The Red Baron, Crashed In His First Solo Flight

- Are There Any Animals Other Than Humans That Commit Suicide?

- How Were Kamikaze Pilots Chosen?

Bonus Fact:

- Due to Albert’s strong resemblance to his aforementioned Godfather, Dr. Hermann Epenstein; the fact that it was shortly after Albert’s birth that Epenstein declared he was going to be the Godfather to all Albert’s mother’s children; the fact that Albert’s sister claimed Albert was Epenstein’s favorite; and that the affair between Epenstein and Albert’s mother started well before Albert’s birth, it is rumored that Albert was actually the son of Dr. Epenstein. However, this is generally discounted by most historians because the dates just barely don’t line up, given a lengthy trip Albert’s mother took to Haiti ending in mid-1894. For reference, Albert was born on March 9, 1895.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|