This Day in History: April 17th- The Rise of English

This Day In History: April 17, 1397

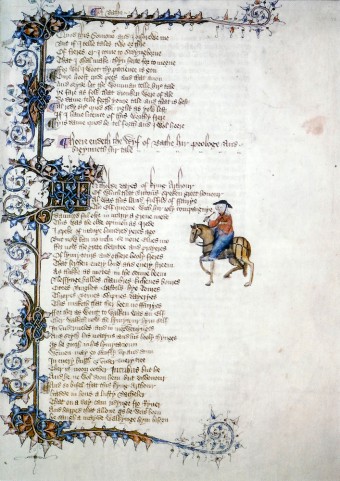

April 17, 1397 marked a turning point in the history of English literature and culture when Geoffrey Chaucer read from his book “The Canterbury Tales” at the court of King Richard II. He read it in English, the language of the common man, instead of the Norman French usually spoken at court. Since the Norman Conquest in 1066, French had been the language of the ruling class. In fact, one of the most famous kings of England, Richard “The Lionheart” barely spoke English at all. English was the language of the peasant, and was slowly dying out. Chaucer would dramatically reverse this trend.

April 17, 1397 marked a turning point in the history of English literature and culture when Geoffrey Chaucer read from his book “The Canterbury Tales” at the court of King Richard II. He read it in English, the language of the common man, instead of the Norman French usually spoken at court. Since the Norman Conquest in 1066, French had been the language of the ruling class. In fact, one of the most famous kings of England, Richard “The Lionheart” barely spoke English at all. English was the language of the peasant, and was slowly dying out. Chaucer would dramatically reverse this trend.

Like the rest of his family who had been in royal service for generations, Chaucer was a professional courtier. During the 1360s, he was involved in peace negotiations during the Hundred Years War. His duties brought him to many of Europe’s greatest cities, including Florence. While there, he discovered the stories of the author Boccaccio, who wrote in Italian, the language of the common people, rather than Latin, the language of the gentry.

Chaucer loved this idea and began writing “The Canterbury Tales”, earthy stories told from the point of view of various people from different classes of medieval English society, from the aristocracy to the worker bees. The characters are embarking upon a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas at Canterbury. Their individual tales mirror their station in life – knight, parson, clerk, etc., for both good and ill.

In Chaucer’s times, reading was often a group activity done in social settings. One orator would read aloud to an audience, much like sitting down as a group to watch a movie.

It’s believed Chaucer had hoped writing The Canterbury Tales in English would aid in it becoming a courtly language. From the moment he read from the book in April 1397, the use of English began to grow. Courtiers began to use it when communicating with each other and the King. English was also being favored over Norman French in the legal system.

The fact that England and France were at war helped tip the scales a bit too. The King of France had ordered the English nobles who had estates in his country to boot it across the Channel and return to France, or forfeit their holdings there. Any of the nobles who chose to remain in England would naturally consider themselves English after that.

When Henry IV ascended the English throne in 1399, English had become so commonplace that no-one batted an eye when he became the first king to take his coronation oath in his people’s language.

Geoffrey Chaucer, who was partly responsible for this change in his country’s vernacular, died a year later on October 25, 1400. His burial marked the tradition of Britain’s most celebrated writers being laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. Chaucer was the very first to be entombed in what is now called “Poet’s Corner.”

Expand for References| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Thank you for this essay, which was very good, except for two errors — one of omission, one of commission.

(1) “The characters are embarking upon a pilgrimage to the shrine of St. Thomas at Canterbury.”

This sentence should have made clear that the shrine was that of St. Thomas Becket (martyred by knights of King Henry II), not of St. Thomas the Apostlie (martyred by pagans in the 1st Century A.D.) nor of St. Thomas More (martyred by King Henry VIII).

(2) “The King of France had ordered the English nobles who had estates in his country to boot it across the Channel and return to France, or forfeit their holdings there.”

The problem here is the use of the phrase, “to boot it.” Although I am 64 and have read tens of millions of words (perhaps more than a billion), I have never encountered the phrase, “to boot it.” I also cannot find it documented on the Internet. I am guessing that it is a very obscure slang phrase (perhaps from a ghetto) — or a colloquialism used in part of Great Britain. Whatever the case may be, it is inappropriate for a writer to use it in a serious essay like the present one. It was possible for me, from the context, to figure out the probable meaning of the phrase, but a reader should not have to do a thing like that.

The truth is that MANY essays at “Today I Found Out” suffer from the presence of colloquialisms (and/or worse) — words and phrases that need to be eradicated. Apparently, the young writers here failed to receive proper guidance (from their teachers, when they were in school) on just how unpleasantly jarring it can be when serious readers encounter unsuitable slang words and phrases in the midst of otherwise serious essays.