A Woman Who Lost the Ability to Smell, Taste, See, and Hear as a Child was the First Deaf-Blind Person to Be Fully Educated

Today I found out about a woman who lost the ability to smell, taste, see, and hear as a child, but went on to become the first deaf-blind person to be fully educated.

Today I found out about a woman who lost the ability to smell, taste, see, and hear as a child, but went on to become the first deaf-blind person to be fully educated.

The woman was Laura Bridgman. Bridgman was born in 1829 and it is thought she had full use of all her senses at birth. However, at the age of two years old, she became sick with scarlet fever, which lasted several weeks before she began to get better. Once she did heal, it became apparent that she had lost her sight and hearing in the process. It was later discovered, after she was educated, that she had lost or never had a sense of smell and she also had nearly no sense of taste.

The one sense she did have was touch. Amazingly, even with only this one sense and no real language, she was still pretty handy around the house as a child. She enjoyed mimicking actions demonstrated to her through touch, so her mother used this to teach her how to do certain household chores. She even learned to sew and knit.

Beyond that, her only real methods of communication were a very simple form of tactile sign language. For instance, she knew if someone pushed her, that she was to go away. If they pulled her, she was to follow along with the pull. When she did an action correctly or what her family wanted, they would pat her on the head. When she did something incorrectly, they would pat her on the back. Eventually, though, Bridgman became too much of a handful for her family as she frequently threw violent temper tantrums and would only obey her father who had to physically overpower her to get that obedience.

At this point, it was generally thought that at deaf-blind person would be unable to be taught even the most rudimentary things, beyond mimicking tasks, let alone be able to be taught to comprehend language. (Although, there are records of a few deaf-blind people learning basic tactile sign language and one French deaf-blind woman who was able to learn French, shortly before Bridgman. However, in these instances, these individuals were not able to become fully educated for a variety of reasons, for more on this, see the Bonus Factoids below).

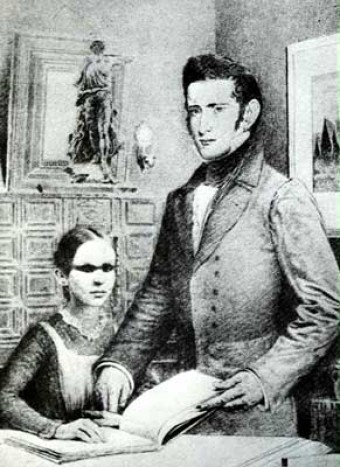

Luckily for Bridgman, though, there was a school for the blind which had been founded the same year as her birth, in 1829, and which opened in 1832 (Perkins School for the Blind). By 1837, many blind people had been successfully educated and one of the instructors there, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, learned of Laura Bridgman’s condition through an account written by the head of the medical department at Dartmouth College, Dr. Mussey. Once Howe learned of Bridgman, he wanted to try and see if he could find a way to teach a deaf-blind person language, which would hopefully be the vehicle to educating her.

Laura, now 8 years old, was then sent to Perkins and began her education. Howe and his assistant, Lydia Hall Drew, first started by devising a way to teach her names of objects in English by giving her objects with their names attached to them in the form of labels with raised letters. Eventually, Laura was able to match labels to objects when the labels were detached. However, at this point, she still had no concept of what she was doing and was only imitating based on memorization, rather than really understanding what the labels meant. Now that she at least associated certain words with objects, even if she didn’t understand the significance, Howe took the exercise further by cutting up the labels and teaching her to rearrange them into the words that she associated with objects.

It was during these exercises that Bridgman finally grasped that objects have names and the labels were indicating the names. This was first indicated by the fact that she suddenly independently wanted to know what the names of objects around her were. Shortly thereafter, she began to fully grasp the concept of an alphabet and, from there, they were able to begin to teach her to use the alphabet and words in communicating.

Once that was accomplished, the rest of her education was relatively straightforward. Her brain now had an engine to drive conscious thought, including essential abstract thought. She proceeded to attend classes like any other student at Perkins, though with various teachers with her at all times finger-spelling everything to her. During her education, she learned mathematics, astronomy, writing, geometry, philosophy, history, biology, etc.

Thanks to Howe being able to successfully reach Bridgman and the fact that he’d been able to do it while she was still fairly young, which allowed her to be able to think abstractly once she had a language for her brain to use, there now was an established method for “reaching” deaf-blind people. Further, it was now proven that deaf-blind people are capable of learning just as well as anyone, assuming they were reached at a young enough age, which was contrary to what most thought at the time.

Howe also published an account of Bridgman’s education which drew the interest of Charles Dickens who came to meet her when she was twelve, in 1842. Dickens then wrote an account of Laura Bridgman in his work, American Notes. In 1886, three years before Bridgman’s death at the age of 59, this account in Dickens’ work resulted in Helen Keller’s parents learning that a deaf-blind person could be educated. It was also through Howe’s methods for teaching Bridgman that Keller was taught.

(Note: If you liked this article, you might also like these: How Deaf People Think and Helen Keller was Not Born Blind or Deaf)

Bonus Facts:

- The doll Anne Sullivan, the teacher of Helen Keller, gave Keller upon their first meeting was made by Laura Bridgman and had been a gift from Bridgman to Sullivan.

- The sickness that cost Bridgman the use of most of her senses also took the lives of her two sisters and brother.

- Bridgman was first able to write her own name in a legible fashion on July 24, 1839, about two years after her education began, at the age of 10 years old. Her progression in mathematics was astoundingly fast, in comparison to her education in language. It took her just 19 days from her first math lesson to learn to add columns of figures from zero to thirty.

- At the age of 20, Bridgman’s education was complete and she returned home. However, because of neglect by her family, who didn’t have time to properly look after her, she developed health problems and it was decided that she should return to Perkins permanently. Her former teacher, Howe, and a friend of hers, Dorothea Dix, set about raising funds to support Bridgman at the school. While there, she taught needlework and helped around the school with domestic chores. She also made money for herself by using her modest fame to help sell various needlework pieces she did. Her primary use of the money tended to be in buying gifts for people she knew and donating to various charities.

- In Bridgman’s free time, her main hobbies were reading and writing letters and poems.

- Bridgman died in 1889 at the age of 59 in her “Sunny Home” at Perkins.

- Howe’s teaching method was inspired by meeting Julia Brace, who was a deaf-blind person that had been taught basic tactile sign language

- Unlike Bridgman, Brace was never able to comprehend abstract thoughts due to not being formally instructed until she was 34 years old, in 1842, also at Perkins. Her education at Perkins was largely a failure, despite her being taught by Howe with the same methods he’d successfully used with Bridgman. Brace made almost no progress due to her inability to grasp any concept that was abstract, and, a mere one year later, she left the school. As a child, because she hadn’t lost her sight and hearing until the age of five, she was able to develop a tactile sign language with her family thanks to once being able to talk. Despite having no capacity for abstract thought, Brace did have an incredible memory for tangible information and even managed to function as a nurse.

- Brace became deafblind after contracting typhus fever.

- Recent research has shown that language is integral in such brain functions as memory, abstract thinking, and, fascinatingly, self-awareness. Language has been shown to literally be the “device driver”, so to speak, that drives much of the brain’s core “hardware”. Thus, deaf people who aren’t taught some form of complex language at a young age, will be significantly handicapped mentally until they learn a structured language, even though there is nothing actually wrong with their brains. The problem is even more severe than it may appear at first because of how important language is to the early stages of development of the brain. Those completely deaf people who are taught no sign language until later life will often have learning problems that stick with them throughout their lives, such as trouble with abstract thought, even after they have eventually learn a particular sign language. It is because of how integral language is to how our brains develop and function that even deaf people, let alone deaf-blined people, were once thought of as mentally handicapped and unteachable.

- Bridgman’s case is not only mentioned famously in Dickens’ American Notes, but also in the French La Symphonie Pastorale, by André Gide. La Symphonie Pastorale is a novel written in 1919 about a pastor who adopts a blind girl. (spoiler alert) The blind girl eventually falls in love with the pastor and becomes hated by nearly everyone in the family except the pastor, due to the amount of time the pastor dedicates to the child. Eventually, one of the pastor’s sons falls in love with the girl and wants to marry her, but the pastor refuses to let him, because he is in love with her too. The story ends with the blind girl receiving a surgery which allows her to see. She then realizes the world isn’t nearly as beautiful as the pastor made out and that she is not in fact in love with the pastor, but his son. She tries to kill herself by drowning, but instead contracts pneumonia from the event and dies. It’s a page turner all right.

- Other famous deaf-blind people include: Sanzan Tani, who by the time he reached adulthood was fully deaf and blind, though he overcame this and continued to function as a teacher; Robert Smithdas, who became the first deaf-blind person to receive a Master’s degree, specializing in vocational guidance and rehabilitation of the handicapped and for a time worked with Helen Keller; and Heinrich Landesmann, who was an Austrian poet and philosopher, who developed a form of tactile signing that now is named after him.

Robert Smithdas is actually still alive today, only retiring in 2008 at the age of 83 years old. Interestingly, his wife Michelle is also deaf-blind. This leads one to wonder how exactly the two do things like locate one another in their home; presumably, something to do with using vibrations in the floor or the like. In any case, it would be fascinating to read about such things as this concerning the two. - As noted, Bridgman enjoyed writing poetry. Her most famous poem, in her day, was “Holy Home”:

Holy home is summerly.

I pass this dark home toward a light home.

Earthly home shall perish,

But holy home shall endure forever.

Earthly home is wintery.

Hard is it for us to appreciate the radiance of holy home because of the blindness of our minds.

How glorious holy home is, and still more than a beam of sun!

By the finger of God my eyes and my ears shall be opened;

The string of my tongue shall be loosed.

With sweeter joys in heaven I shall hear and speak and see.

What glorious rapture in holy home for me to hear the angels sing and perform upon instruments!

Also that I can behold the beauty of heavenly home.

Jesus Christ has gone to prepare a place for those who love and believe Him.

My zealous hope is that sinners might turn themselves from the power of darkness unto light divine.

When I die, God will make me happy.

In heaven music is sweeter than honey, and finer than a diamond.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Sadly, Robert Smithdas passed away in 2014. However, for those curious about his life and how he communicated/functioned at home with his deaf-blind wife, Michelle, there is a Barbara Walters interview with the couple available on youtube. Part 1 is here: https://youtu.be/wtonN82q6Wo

Thoroughly enjoyable read. The thing that struck me, is how exciting and overwhelming it must have been for her during the period where she developed abstract thought. Though it was probably a process that spanned over time. Nevertheless, what a revelation that must have been even, as a child. It’s like learning to think.

I don’t believe abstract thought depends on early exposure to language. Abstract language does, as do certain aspects of social cognition. But many of the things we consider abstract thought are done by animals with only rudimentary communication systems – things like planning for the future and judging how well they know something. There are animals who think fairly abstractly without any evidence that they have anything close to human language.