Sullivan Ballou’s Letter

Today I found out about Sullivan Ballou’s letter to his wife written just a few days before the first major land battle of the American Civil War, the First Battle of Bull Run, fought this day (July 21) in 1861 in Manassas, Virginia.

Today I found out about Sullivan Ballou’s letter to his wife written just a few days before the first major land battle of the American Civil War, the First Battle of Bull Run, fought this day (July 21) in 1861 in Manassas, Virginia.

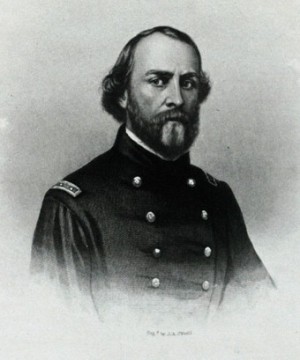

Ballou was a major in the U.S. Army and a member of the Rhode Island Volunteers. Before joining the army, Ballou was a self made lawyer and budding politician. He lost his parents at a very young age and was forced to fend for himself, eventually attending Brown University and the National Law School in Ballston, New York. Shortly after he began practicing law, he was elected to the Rhode Island House of Representatives as a clerk and eventually became speaker. Being a big supporter of Abraham Lincoln, when war began, he left his law practice and birthing political career and volunteered for military service.

This is his letter to his wife, Sara Hunt Shumway, later named Sara Ballou. It was written days before the first major land battle of the American Civil War, the First Battle of Bull Run (also called the First Battle of Manassas by the Confederacy):

My very dear Sarah:

The indications are very strong that we shall move in a few days—perhaps tomorrow. Lest I should not be able to write you again, I feel impelled to write lines that may fall under your eye when I shall be no more.

Our movement may be one of a few days duration and full of pleasure—and it may be one of severe conflict and death to me. Not my will, but thine O God, be done. If it is necessary that I should fall on the battlefield for my country, I am ready. I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American Civilization now leans upon the triumph of the Government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution. And I am willing—perfectly willing—to lay down all my joys in this life, to help maintain this Government, and to pay that debt.

But, my dear wife, when I know that with my own joys I lay down nearly all of yours, and replace them in this life with cares and sorrows—when, after having eaten for long years the bitter fruit of orphanage myself, I must offer it as their only sustenance to my dear little children—is it weak or dishonorable, while the banner of my purpose floats calmly and proudly in the breeze, that my unbounded love for you, my darling wife and children, should struggle in fierce, though useless, contest with my love of country?

I cannot describe to you my feelings on this calm summer night, when two thousand men are sleeping around me, many of them enjoying the last, perhaps, before that of death—and I, suspicious that Death is creeping behind me with his fatal dart, am communing with God, my country, and thee.

I have sought most closely and diligently, and often in my breast, for a wrong motive in thus hazarding the happiness of those I loved and I could not find one. A pure love of my country and of the principles have often advocated before the people and “the name of honor that I love more than I fear death” have called upon me, and I have obeyed.

Sarah, my love for you is deathless, it seems to bind me to you with mighty cables that nothing but Omnipotence could break; and yet my love of Country comes over me like a strong wind and bears me irresistibly on with all these chains to the battlefield.

The memories of the blissful moments I have spent with you come creeping over me, and I feel most gratified to God and to you that I have enjoyed them so long. And hard it is for me to give them up and burn to ashes the hopes of future years, when God willing, we might still have lived and loved together and seen our sons grow up to honorable manhood around us. I have, I know, but few and small claims upon Divine Providence, but something whispers to me—perhaps it is the wafted prayer of my little Edgar—that I shall return to my loved ones unharmed. If I do not, my dear Sarah, never forget how much I love you, and when my last breath escapes me on the battlefield, it will whisper your name.

Forgive my many faults, and the many pains I have caused you. How thoughtless and foolish I have often been! How gladly would I wash out with my tears every little spot upon your happiness, and struggle with all the misfortune of this world, to shield you and my children from harm. But I cannot. I must watch you from the spirit land and hover near you, while you buffet the storms with your precious little freight, and wait with sad patience till we meet to part no more.

But, O Sarah! If the dead can come back to this earth and flit unseen around those they loved, I shall always be near you; in the garish day and in the darkest night—amidst your happiest scenes and gloomiest hours—always, always; and if there be a soft breeze upon your cheek, it shall be my breath; or the cool air fans your throbbing temple, it shall be my spirit passing by.

Sarah, do not mourn me dead; think I am gone and wait for thee, for we shall meet again.

As for my little boys, they will grow as I have done, and never know a father’s love and care. Little Willie is too young to remember me long, and my blue-eyed Edgar will keep my frolics with him among the dimmest memories of his childhood. Sarah, I have unlimited confidence in your maternal care and your development of their characters. Tell my two mothers his and hers I call God’s blessing upon them. O Sarah, I wait for you there! Come to me, and lead thither my children.

Sullivan

Sullivan Ballou was mortally wounded along with 93 of his men just 7 days later at the First Battle of Bull Run and died shortly thereafter at the age of 32 with his wife being 24. The letter was found in his trunk and delivered to his wife by Governor William Sprague, who had traveled to Virginia to retrieve the remains of the fallen Rhode Island soldiers.

Bonus Facts:

- In an attempt to better direct his men, Ballou placed himself at the front of his regiment, rather than the traditional back as most officers would have done. This made him easy pickings for Confederate troops. He was hit with a 6 pound shot which tore off his leg and killed his horse. He was then carried off the field and died a week later.

- Sara Ballou never re-married and died at the age of 80 years old in 1917. They are buried next to each other in the Swan Point Cemetery in Providence, RI.

- Sullivan Ballou’s body ended up being hard to track down when the Governor came to retrieve it. The place where he was initially buried by U.S. soldiers had been desecrated by Confederate soldiers. When they dug the grave, they found no body. A young black girl recounted to them a tale of what happened to it, which was later verified. Soldiers from the 21st Georgia Regiment had dug up the grave of Kernel Slocum and Major Sullivan Ballou. They had decapitated Ballou and mutilated his corpse and then burned it. They then used the bones as trophies. His body was never found, but evidence at the scene where she said the body was burned supported the girl’s story. Although, she thought it was Slokum, not Ballou that had been mutilated; it was later found it had been Ballou. The ashes from the fire were taken and eventually buried in Swan Point Cemetery in Providence, RI.

- Union casualties in the battle were estimated at 460 killed; 1,124 wounded; and 1,312 missing or captured. Confederate casualties were 387 killed; 1582 wounded; and 13 missing or captured. These were staggering mortality numbers compared to most battles of the day, but would soon be eclipsed by coming battles in the Civil War, such as the battle at “The Wilderness” from May 5-7 which resulted in nearly 18,000 Federal deaths and a similar amount of Confederate deaths estimated. For comparison, on D-Day during WWII “only” 1,465 Americans were killed and about 2,500 allied troops.

- The total number of American deaths during the Civil War were about 292,000 in battle, which was about 2% of the population, and about 625,000 total killed as a result of the war (including those dead of disease and the like, which was a major problem in soldier’s camps). That is a total of about 4.3% of the U.S population. By today’s population numbers that would be about 13.32 million Americans.

- Union casualties at the Second Battle of Bull Run were about 10,000 killed out of 62,000 that took part in the battle. The Confederate casualties were about 1,300 killed out of 50,000 engaged. As you can tell from those numbers, the Union suffered from a string of incredibly incompetent Generals while the South was lead by one of the greatest Generals in the history of the world, Robert E. Lee.

- General Lee was offered the position of the head of the Union army by Abraham Lincoln, but decided to lead the Confederate army instead as he couldn’t bring himself to lead troops against his native Virginia. Despite the Confederates being vastly outnumbered and not as well equipped as the North, Lee and his right hand man, Stonewall Jackson, managed to post victory after victory against the North, primarily due to Lee’s brilliance, Jackson’s audacity, and the North’s moronic Generals.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

That is one incredible letter! I don’t know of anyone, myself included (a Viet

Nam veteran) who feels/felt that way when facing death/battle. What commitment & moral compass.

Too bad they couldn’t have just “talked it out”.

While this is one of my favorite letters from the Civil War and you present the details around his death and battle well, you need to re-do the death figures you list for the Battle of the Wilderness. You have casualties (dead, wounded, captured, and missing) mixed up with just the dead. For instance, the Battle of Antietam had approximately 3,600 killed (out of approx. 23,000 total casualties) and is typically considered the bloodiest day of the war (other days may have been worse but were part of longer battles and it is difficult to separate casualty numbers) and is often compared with D-Day.

Why the hell didn’t they make us recite THIS in 5th grade instead of the far-inferior Gettysburg Addres??