This Day in History: May 14th- We Want Beer

This Day In History: May 14, 1932

During the height of the Great Depression, getting 100,000 people hyped up about anything other than available paid work would seem an impossible task. Jobs were scarce, money was tight, and morale was low. But there was one thing that could drive the masses to the streets of New York City in the thousands – Beer.

During the height of the Great Depression, getting 100,000 people hyped up about anything other than available paid work would seem an impossible task. Jobs were scarce, money was tight, and morale was low. But there was one thing that could drive the masses to the streets of New York City in the thousands – Beer.

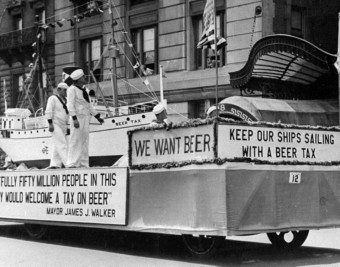

On May 14, 1932, New York City Mayor and consummate showman Jimmy Walker led a Beer for Taxation march, which popularly became known as the “We Want Beer!” parade, through the streets of the city. “The parade will furnish the best count of noses I can think of, much better than the passing of resolutions, or the writing of letters to Representatives in Congress,” Walker explained to the New York Times. An estimated 100,000 people turned out to show their distaste for the 18th amendment, and their love for beer. (See: How Crowd Sizes are Estimated)

When Congressman Emanuel Celler heard about the event, he said he’d come and bring a bunch of friends. You’d be able to pick him out in the crowd by the two signs he’d be holding: “Never Say Dry” and “Open the Spigots and Drown the Bigots.” The Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Legion and the Grand Army of the Republic (a group of Civil War veterans) also turned out to march in the parade. Students and society matrons also joined the fray.

By the early 1930s, it was painfully obvious that prohibition was a failure, despite once being a hugely popular concept, with most of the ills of society being blamed on alcohol for various reasons, some legitimate due to drinking trends at the time, particularly for factory workers, and others not.

In fact, for a time in the 1920s, the government was even intentionally poisoning certain known alcohol supplies, killing more than 10,000 American citizens who technically weren’t even doing anything illegal by drinking; the law only stated you couldn’t manufacture, transport, or sell alcohol. You’d think the populace on the whole would be upset about this, but in fact there were calls in Congress to increase this program to kill off more of these drinkers who were seen as cancers of society. As one Chicago Tribune article in 1927 stated: “Normally, no American government would engage in such business. … It is only in the curious fanaticism of Prohibition that any means, however barbarous, are considered justified.”

(Although, it should be noted that this was also an era when eugenics was a hugely popular concept throughout much of the developed world, even supported by the likes of Winston Churchill. The popularity of eugenics reached its crescendo just before WWII, dying out after for obvious reasons, though of course minor elements of it are still practiced today in many nations.)

However, despite people publicly taking the so-called moral high ground when it came to alcohol, the potential for drinking poison when indulging, and the ban on transporting, manufacturing, or selling alcoholic beverages, people still drank… A lot. In 1930 alone, 2.5 billion gallons of beer were consumed in the United States. Reflecting this slight hippocrasy, Will Rogers once joked about southern prohibitionists, “The South is dry and will vote dry. That is, everybody sober enough to stagger to the polls.”

This all added up to millions of lost federal and local taxes annually. The New York Times speculated that if the Federal government reinstated its former tax of six dollars per barrel, $500 million (about $7 billion today) of new tax revenue could be generated, and that the same sum could be expected at the state level. This was quite the selling point to a nation suffering severe economic stagnation.

Those calling for the end to prohibition also pointed out that gangsters, like Al Capone, controlled the manufacture and sale of alcohol. Between 350-400 murders per year, among a large amount of other types of criminal activity, could be traced to the lucrative but obviously deadly bootlegging underworld. Making alcohol legal again would cut the major source of funding to these gangsters, as well as freeing up police to pursue other criminal activity.

Other cities across America followed New York’s lead. Chicago’s Beer for Prosperity parade attracted 40,000 people, and the majority of Daytona Beach’s 17,000 citizens participated in its parade, which commenced with marchers drinking from a 20-gallon keg of beer. Naughty, naughty.

Bostonians were served beer on the Common by city councilmen with Mayor James Curley’s blessing, who remarked, “Don’t blame us if the brewer makes a mistake and delivers a beverage of more than half a percent alcoholic content.”

Prohibition was clearly on borrowed time in America.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- What are Blue Laws?

- Does Canadian Beer Really Contain More Alcohol Than Beer Made in the United States?

- The Good and the Bad of Vaporizing and Inhaling Alcohol

- How Al “Scarface” Capone Got His Scars

- Does Alcohol Kill Brain Cells?

Bonus Facts:

- Prohibition wasn’t the only time the U.S. Government decided to poison the supply of some illegal substance in order to try to scare people away from using it. In the 1970s the government sprayed marijuana fields with Paraquat, which is an herbicide. They thought this had the dual benefit of killing large portions of the crop and also scaring people away from buying marijuana in those areas because the surviving plants would essentially be laced with a mild toxin. Public outcry at the time however, forced the government to stop doing this.

- The 18th Amendment itself was repealed in December of 1933. When President Roosevelt signed the Cullen-Harrison Act, he made the now famous remark, “I think this would be a good time for a beer.” A mere one day after the Cullen-Harrison Act went into effect on April 7, 1933, Anheuser-Busch, Inc, sent a case of Budweiser to the White House as a gift to President Roosevelt.

- While the Volstead Act banned the manufacturing, sale, and transport of alcohol, it did allow home brewing of wine and cider from fruit. An individual home was allowed to produce up to 200 gallons per year.

- Grape growers of the day began selling “bricks of wine”, which were primarily blocks of “Rhine Wine”. These often included the following instructions: “After dissolving the brick in a gallon of water, do not place the liquid in a jug away in the cupboard for twenty days, because then it would turn into wine.” Also, because the Volstead Act did not ban the consumption or storage of alcohol, before the act went into effect, many people stockpiled various alcoholic beverages.

- “Operation Pipe Dreams” was a 2003 nationwide United States investigation which targeted business selling drug paraphernalia. In the end, hundreds of businesses and homes were raided nationwide. Fifty-five people were charged with trafficking of illegal drug paraphernalia and eventually fined and generally given home detentions. The estimated cost of the operation was around twelve million dollars or about $220,000 per person charged and about 2,000 officers involved or about 36 officers per charge.

- The word “prohibition” comes from the Latin “prohibitionem”, meaning “hindering or forbidding”. It was used to mean “forced alcohol abstinence” as early as 1851.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

There was a brand of beer sold in Taiwan (an import) that was called I Want Beer.

http://my.execpc.com/A8/A0/cathyf/pictures/beerthum.JPG

This article epitomizes the saying “those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.” We’re repeating it now on a whole new level. The War on Drugs has wasted more money, killed more people, and produced some monsters that make Al Capone look like a saint. Oh and most cartels make more in a day than entire organizations made through all of prohibition, even if you adjust the relative value of the money.