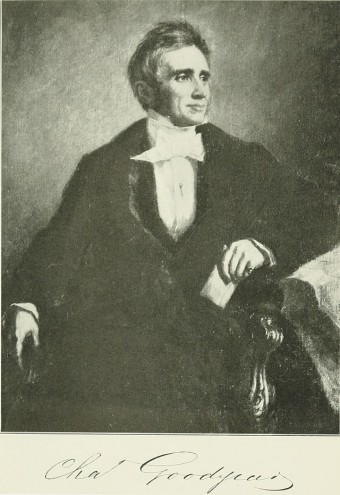

The Luckless Rubber Maven: Charles Goodyear

Nineteenth century America was a good time to be inventor. With the right timing, invention, marketing, and patent, one could become rapidly rich. Elias Howe (the sewing machine), Samuel Morse (Morse code), and Cyrus McCormick (the mechanical reaper) were just a few of the pioneers who reaped the financial rewards of their business acumen. Despite being the inventor of one of the most influential innovations of the past two hundred years, Charles Goodyear was not like his peers. Due to bad luck, losing a patent battle, and rather lackluster marketing skills, Goodyear died little known and with massive debt, not to mention his rather tragic family life. Here is the story of the luckless rubber maven, Charles Goodyear.

Born December 29, 1800 in New Haven, Connecticut, Charles was the oldest of six children and the son of Amasa Goodyear. His family had already been in New Haven for generations, descendants of Stephen Goodyear, one of the founders and leading citizens of New Haven when it was established in 1638 (long considered to be America’s first planned city). Charles’s father was a pious and respected man of decently wealthy means, a “jack-of-all-trades” and quite a good businessman. When Charles was young, his father bought a patent for a manufacturer of buttons and opened a new business about eighteen miles from New Haven, in the town of Naugatuck. There, he became the first US manufacturer of pearl buttons in 1807 and, during the war of 1812, supplied the government with all its metal buttons. Charles worked for his enterprising father, tending to orders, as well as the farm his family also owned.

At the age of 17, Charles Goodyear, with his father’s encouragement, moved to Philadelphia to work and apprentice at a hardware company called Rogers and Brothers. He returned to Connecticut in 1820/21 and was made a business partner in his family’s business. Around that time, the business had pivoted from making buttons to agricultural tools to other various hardware needs.

On August 24, 1824, Charles was married to Clarissa Beecher, “a lady every way fitted to be the companion and comforter of his life.” Additionally, Charles was doing so well in the business with his father, he decided it was time to open his own hardware store. He made the move to Philadelphia and opened what is still considered the first retail domestic hardware store in the United States. For many years prior to this, customers in the States were generally distrusting of buying goods made in America. Quite simply, they still thought goods made in England were of better quality. As the 19th century worn on, this misconception went away and, as the only retail domestic hardware business open in the country, “a handsome fortune was accrued by the firm.”

In 1829, all of this good fortune came crashing down on Charles Goodyear. Believing he had enough capital to extend his operations outside of Philadelphia, he shipped his goods to buyers in the Mid-Atlantic and South, only to have them consistently default on payments thanks to the Tariff Act of 1828, which dealt a crippling blow to the once rising Southern economy. As their economy fell, many of Goodyear’s customers in the South simply decided to stop paying him. Additionally, a rather hideous bout of dysentery resulted in Goodyear being bedridden for a time and unable to work.

In 1830, his once promising business went under and Goodyear was thrown into debtor’s prison, due to failure to pay off creditors. Debtors’ prison was common then, but no less inhumane- imprisoning those who most needed to work to pay off debts. As described by Charles Slack in his book Noble Obsession, “Debtors’ prison represented probably the worst institutional hypocrisy outside of slavery for a young nation professing itself to be dedicated to liberty, justice, and individual rights.”

To make matters worse, between 1831 and 1833, two of Charles’ young children passed away, while his own health continued to decline. At this time, not knowing how to provide for his family, Charles turned to the same thing his father did with buttons so many years ago – the pursuit of making a known product better.

Goodyear knew about the fascinating ability of rubber as a manufacturing tool, using it in several products he produced in his time with his hardware store. Rubber wasn’t a new discovery, being made from the milky white sap (latex) of Hevea brasiliensis trees and used by the Mayans and Aztecs long before Europeans arrived. In the early 19th century, there was a certified rubber boom as it was used to make clothes weatherproof. The problem was that pure rubber froze in the cold and melted and became sticky in the heat, while producing a rather pungent odor.

Goodyear was exposed to this in New York City when he was taken into the hot storage room of the Roxbury India Rubber Company (the first successful American rubber company) after claiming to a sales agent he could make a better air valve for their intertubes. There, he saw – and smelled – the dark side of rubber – melted, mangled, and stinky. From that point forward, Goodyear devoted his life to improving rubber for commercial use.

Goodyear immediately went to work on this venture, buying rubber cheaply from Brazil at only a few pennies a pound, despite knowing very little about the substance. He initially turned to turpentine and experimented with the chemical, turning the dry, hard rubber into liquid. Despite his hard work, he rarely earned any money from it and, was put into debtors’ prison several times between 1834 and 1838, further plunging his family into poverty. As a result, he was forced to sell many of his family’s possessions in order to survive. Still, he was determined, working and mixing rubber all day – so much so, that neighbors called the police complaining of foul odors morning and night.

Good news would come and go. He had several investors who believed in his work, only to bail when the financial crisis of 1836/1837 engulfed the whole country. He was able to make money off of selling rubber tablecloths, only to see them age poorly. A business partner gave him enough money to open a factory in Staten Island, only for the partner to go bankrupt due to another venture, resulting in the factory closing within months. Finally, after many failures, in late 1838, Goodyear met Nathaniel Hayward, the man who would help him solve all his rubber problems. Or so he thought.

In his experiments, Goodyear had come across Hayward’s work of drying rubber with sulfur. It seemed, at least initially, that this made the rubber, stronger and less susceptible to temperature changes (though still emitting a distinctive odor, but now it was sulfur). Hayward and Goodyear began working together, with Goodyear bringing his extensive trial and error knowledge to the partnership.

There is considerable legend around how the vulcanization process came to be discovered by Charles Goodyear. (Named after Vulcan, the Roman god of fire. This is a chemical process for converting natural rubber into a stronger, more durable material by adding a certain amount of sulfur and heat.) Some say, in an argument with Hayward, he threw a piece of rubber covered sulfur onto a burner, when they both noticed the rubber didn’t go up in flames, but charred… and harden. Some say that Hayward discovered it himself and that Goodyear tried to buy him out. Or perhaps he simply discovered it during one of his numerous trial-and-error experiments with rubber.

Whatever the case, in 1839, Goodyear purchased U.S. Patent 1090 – IMPROVEMENT IN THE MODE OF REPAIRING CAOUTCHOUC WITH SULPHUR FOR THE MANUFACTURE OF VARIOUS ARTICLES – from Hayward. Additionally, in 1841, Hayward testified in court that Goodyear was the true inventor of the vulcanization process. Goodyear was convinced that, “If the process of charring could be stopped at the the right point, it might divest the gum of its native adhesiveness throughout, which would make it better than native gum.”

If Charles Goodyear thought that his life of struggle and poverty was over thanks to his revolutionary product, he was sorely mistaken. As the 1866 biography Trials of an Inventor: Life and Discoveries of Charles Goodyear states, “God had further trials in store for him.”

1840, only a year after his discovery, was one of the worst of Goodyear’s life. He still was fiddling with exactly how much heat, sulfur, and pressure was needed to make the best rubber possible. Dysentery and gout still plagued him, with Goodyear constantly fearing he would die without completing his life’s work. He again was jailed, this time for not paying a five dollar hotel bill. Tragically, another infant son of his died, making it six children at this point that he and his wife had lost.

Finally, after nailing down the optimal formula, he patented the process in 1844, but that didn’t put an end to his struggles either. “Patent pirates” kept forcing him to prosecute patent infringement cases, 32 in all. Around this same time, in honor of his father, Goodyear built a rubber factory in the very same town his father had a button factory in – Naugatuck. While this turned Naugatuck into the rubber capital of the United States, if not the world at the time, it wasn’t particularly financially prudent for Goodyear to scale up, while still in the process of paying off debts and fighting patent pirates.

His patent problems continued when he applied for a patent in England to ensure increased rubber revenue. His patent request was was denied because of Thomas Hancock’s own patent filed mere weeks earlier. Sometime between 1839 and 1843, Hancock had come into the possession of a piece of Goodyear rubber. After a close study, he was able to figure out nearly the exact formula to recreate Goodyear’s process of vulcanization. Goodyear fought back and an ugly and quite lengthy court case ensued, only for the judge to rule in favor of Hancock. Goodyear was out of luck again.

Goodyear continued to try to pay off his debts and protect his patents, but in late June of 1860, all of this took a backseat when he heard that yet another of his children was dying, this time one of his daughters. He raced to New York to see her, but upon arrival, he was told she had already died. Goodyear reportedly collapsed on the spot and shortly thereafter was pronounced dead on July 1, 1860 at 59 years old. Despite the culmination of his life’s work ultimately revolutionizing many industries, he died relatively unknown and approximately two hundred thousand dollars in debt (about $5 million today).

However, Charles Goodyear, keeping things in perspective, once wrote, “Life should not be estimated exclusively by the standard of dollars and cents. I am not disposed to complain that I have planted and others have gathered the fruits. A man has cause for regret only when he sows and no one reaps.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The History of the Goodyear Blimp

- Why Tires Today are Black Instead of White and what Crayola Crayons Has to Do With The Switch

- 10 Common Items That Were Invented by Accident

- Were Footballs Ever Really Made of Pigskin?

- Where the Words “Crayola” and “Crayon” Come From

Bonus Fact:

- Goodyear Tires was founded in 1898 and was named after Charles Goodyear. He had no affiliation with the company, besides the naming honor they bestowed upon him.

- THE APPLICATIONS AND USES VULCANIZED GUM-ELASTIC; with DESCRIPTIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR MANUFACTURING PURPOSES. By Charles Goodyear

- Charles Goodyear – Biography.com – Library of Congress

- The Rubber Band: Holding It Together Since 1820 – Today I Found Out

- Charles Goodyear – Wikipedia

- The Charles Goodyear Story – Goodyear.com

- IMPROVEMENT iN THE MODE OF RREPARING CAOUTCHOUC WITH SULPHUR FOR THE MANUFACTURE 0 VARIOUS ARTICLES. – Google Patents

- Charles Goodyear Biography – Biography.com

- Charles Goodyear and the Vulcanization of Rubber – ConnecticutHistory.org

- Noble Obsession: Charles Goodyear, Thomas Hancock, and the Race to Unlock … By Charles Slack

- A Centennial volume of the writings of Charles Goodyear and Thomas Hancock

- Trials of an Inventor: life and discoveries of Charles Goodyear, etc By Bradford Kinney PEIRCE

- Charles Goodyear – Proquest

- Charles Goodwin – jstor.org

- Peirce, B. K. (Bradford Kinney). Trials of an inventor : life and discoveries of Charles Goodyear. New York, [1866]

- Tariff of Abominations – Wikipedia

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

One comment