Why the Mass Avoidance of Some Business is Called “Boycotting”

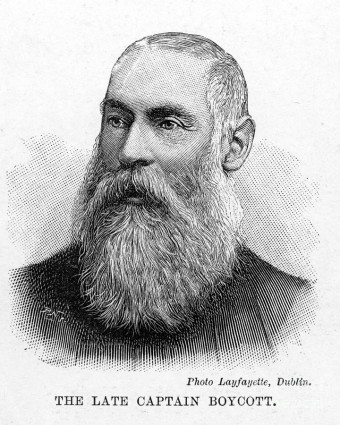

This term was named after a nineteenth century Englishman, Captain Charles C. Boycott (who originally had the surname “Boycatt,” but the family changed the spelling when he was nine years old). If you guessed that at a certain point Captain Boycott became quite unpopular with the masses, you’re correct.

This term was named after a nineteenth century Englishman, Captain Charles C. Boycott (who originally had the surname “Boycatt,” but the family changed the spelling when he was nine years old). If you guessed that at a certain point Captain Boycott became quite unpopular with the masses, you’re correct.

Shortly before Boycott would find himself boycotted, the situation in Ireland was that just 0.2% of the population owned almost every square inch of land in Ireland. Most of the owners of the land also didn’t live in Ireland but simply rented their land out to tenant farmers, generally on one-year leases.

In the mid-nineteenth century, many of these tenant farmers banded together with three goals: “Fair Rent, Fixity of Tenure, and Free Sale”. One particular organization that emerged in the 1870s pushing these “Three F’s,” among other things, was the Irish National Land League.

This brings us to September of 1880. The leader of the Land League, Parliament member Charles Stewart Parnell, was giving a speech to many of the members of that organization. During the speech, after the crowd, in true mob-like fashion, expressed that any tenant farmer who bids on an evicted neighbor’s land should be killed, Parnell humbly suggested that another tack should be used.

Rather than murder the individual, he proposed it would be more Christian to simply

…shun him on the fair green and in the market place, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of the country, as if he were the leper of old – you must show him your detestation of the crime he committed.

Essentially, they were to be boycotted, but they didn’t have that term yet, though they wouldn’t have to wait long. The first documented reference of “Boycott” being used as a verb was just two weeks after that speech.

At the time, Captain Charles Boycott, now retired from the military, was working as a land manager for the third Earl of Erne, John Crichton. The harvest that year wasn’t turning out well for many farmers, so as a concession to tenants, Boycott decided to reduce their rent by 10%. Rather than accept this, his tenants demanded a 25% reduction, which Boycott’s boss, the Earl of Erne, refused. In the end, 11 of the Earl’s tenants didn’t pay their rent.

Thus, a mere three days after this speech, Boycott began the process of serving eviction notices to those who hadn’t paid, sending out the Constabulary to do this. Needless to say, this did not go over well with the already riled up masses.

Upon the tenants realizing eviction notices were going out, the women of the area began throwing things such as rocks and manure at those delivering the notices until the Constabulary left without being able to serve all the notices to the head of the households, which was required by law for the eviction notice to be considered served. Without the notices delivered, nobody had to leave their homes.

Next, the teeming masses decided to use Parnell’s proposed social ostracism against Boycott and anyone who worked under him. Soon, those who worked under Boycott began leaving his service, often with those workers being coerced and threatened by others until they, too, joined in the ostracizing of Boycott.

This ultimately left Boycott with a large estate to manage, but no workers to farm the remainder of the crops. Other businesses also stopped being willing to do business with Boycott; he couldn’t even buy food locally and getting it from afar was difficult as carriage drivers, ship captains, and letter handlers on the whole wouldn’t work with him.

In late November, this led to Boycott being forced to leave his home, fleeing to Dublin. Even there, he was met with hostility and businesses that were willing to serve him were threatened with being “boycotted.”

The practice of boycotting spread, and within a decade whenever a business did something to the dislike of the Irish National Land League, the business would quickly find themselves boycotted, with the name for the practice sticking due to the wide publication of Boycott’s plight in the news. By 1888, just eight years after Boycott was first boycotted, the word even made it into the New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, better known today as the Oxford English Dictionary.

The word spread to other European languages and quickly made it over to America when Captain Boycott visited friends in Virginia, attempting to do so in secret -registering under the name “Charles Cunningham.” The newspapers caught wind of his arrival anyway and widely publicized his history, which got the term firmly planted in American English as well.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- The Business That Would Evolve Into Taco Bell Started Out Selling Hot Dogs

- Steve Jobs’ First Business was Selling Blue Boxes that Allowed Users to Get Free Phone Service Illegally

- Pre-Sliced Bread Was Once Banned in the United States

- When Pinball was Illegal

- The Surprisingly Long History of Nintendo

Bonus Fact:

- Boycott did get his crops harvested the year he was boycotted, finding 50 workers from out of town to come harvest his crops. The problem was that the locals did not take kindly to this, so the government had to step in and had nearly one thousand soldiers escort the workers and protect them while they worked. Funny enough, this ended up costing the British government about £10,000. How much were the crops worth? About £500.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Good stuff. You might also want to add a bonus fact, or separate article, about the meaning and origin of “sending someone to Coventry”, since that is mentioned here:

“by putting him in moral Coventry”

Thanks for the information, I love getting an education from this site…Its good!