The Truth About Legendary Highwayman Dick Turpin

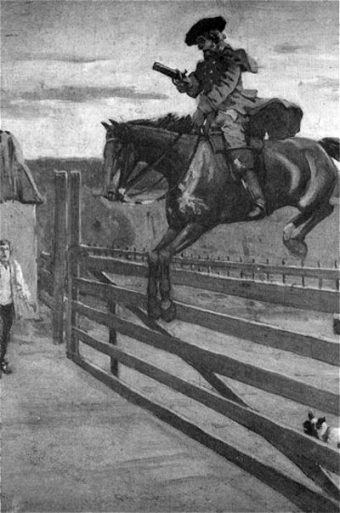

Richard Turpin, better known by his nickname, Dick, was a legendary highwayman who stalked the English countryside. A century or so after his death by hanging in 1739, Turpin was idealised as a dashing rogue or gentleman thief type in a multitude of supposedly factual stories purportedly based on his life.

Richard Turpin, better known by his nickname, Dick, was a legendary highwayman who stalked the English countryside. A century or so after his death by hanging in 1739, Turpin was idealised as a dashing rogue or gentleman thief type in a multitude of supposedly factual stories purportedly based on his life.

In reality, he was not exactly dashing, with a face covered in pox scars. More importantly, far from being a lovable rogue, Dick Turpin was kind of, well, a dick (see: Why Dick is Short for Richard). Further, many of his supposed “feats” were actually gleaned from the lives of less well-known highwaymen, most notable, Swift Nick Nevison. Compared to the ruthless Turpin, Nevison was practically a gentlemen who, while still very much a scoundrel compared to more law abiding citizens, specialized in robbing the rich (which makes sense because, well, they have a lot more money than the poor), rarely used violence and was often astonishingly polite to many he stole from. (See: Swift Nick Nevison and His Remarkable Dash to Secure an Alibi)

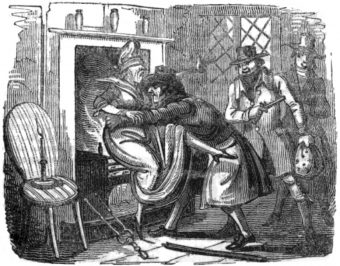

In contrast, the reality was that Turpin had no qualms about brutally beating, mutilating, raping, or robbing just about anyone, including the elderly and the infirm. He once even threatened to roast an old lady alive if she didn’t tell him and his gang where she’d hidden her life savings. As reported by Read’s Weekly Journal on February 8, 1735:

On Saturday night last, about seven o’clock, five rogues entered the house of the Widow Shelley at Loughton in Essex, having pistols &c. and threatened to murder the old lady, if she would not tell them where her money lay, which she obstinately refusing for some time, they threatened to lay her across the fire, if she did not instantly tell them, which she would not do. But her son being in the room, and threatened to be murdered, cried out, he would tell them, if they would not murder his mother, and did, whereupon they went upstairs, and took near £100, a silver tankard, and other plate, and all manner of household goods. They afterwards went into the cellar and drank several bottles of ale and wine, and broiled some meat, ate the relicts of a fillet of veal &c. While they were doing this, two of their gang went to Mr Turkles, a farmer’s, who rents one end of the widow’s house, and robbed him of above £20 and then they all went off, taking two of the farmer’s horses, to carry off their luggage, the horses were found on Sunday the following morning in Old Street, and stayed about three hours in the house.

In another “roasting” incident, they robbed a 70 year old farmer by the name of Joseph Lawrence in Edgware. Dragging the poor old man around by his nose with his pants around his ankles, they beat him severely on his backside and head, and then shoved him down to sit bare-butted on a fire. While this was happening, other members of the gang went and raped one of the man’s maids.

Over the years though, the “legend” of Turpin became muddled and rather than being painted as the rapist and brutal thief he was, he became a handsome and lovable ne’er-do-well with a heart of gold, being romanticised in everything from novels to cheesy 1980s TV shows.

Turpin’s life of serious crime began with the Gregory Gang, initially made up of Samuel, Jeremiah, and Jasper Gregory, along with Joseph Rose, Mary Brazier, John Jones, Thomas Rowden, and John Wheeler. Turpin appears to have become involved with the gang thanks to their early days of poaching deer and subsequently needing the services of a butcher to dispose of it. Turpin later became more directly involved with the group when they moved from poaching to robbing dozens of people of their livelihoods. Over his years with them, he was complicit in torture, beatings, rape as well as committing at least one murder (a gamekeeper called Thomas Morris who’d tried to capture Turpin as he was hiding in Epping forest but was instead shot by him).

As a result of all this, the water was getting hot around Turpin, as members of the famed gang were getting snapped up by bounty hunters. After the murder of Morris, The Gentleman’s Magazine noted in June of 1737:

It having been represented to the King, that Richard Turpin did on Wednesday the 4th of May last, barbarously murder Thomas Morris, Servant to Henry Tomson, one of the Keepers of Epping-Forest, and commit other notorious Felonies and Robberies near London, his Majesty is pleased to promise his most gracious Pardon to any of his Accomplices, and a Reward of 200l. to any Person or Persons that shall discover him, so as he may be apprehended and convicted. Turpin was born at Thacksted in Essex, is about Thirty, by Trade a Butcher, about 5 Feet 9 Inches high, brown Complexion, very much mark’d with the Small Pox, his Cheek-bones broad, his Face thinner towards the Bottom, his Visage short, pretty upright, and broad about the Shoulders.

After this, Turpin attempted to hide from the law by assuming the identity John Palmer and absconding from the London area, eventually finding his way to a small town in Yorkshire bordering the river Humber called Brough, presenting himself as a down-on-his-luck butcher who now made a living as a horse trader.

Had he at this point turned himself into a law-abiding citizen, Turpin likely would have gotten away with the countless nefarious exploits of his youth. However, old habits die hard and to fund his new life, Turpin would often travel across the river from Yorkshire to nearby Lincolnshire to steal sheep and horses. However, the event that really sealed Turpin’s fate is when he shot a man’s cockerel supposedly after a failed hunt in 1738 resulted in a frustrated and drunken Turpin deciding to take his aggression out on the cock.

Had he at this point turned himself into a law-abiding citizen, Turpin likely would have gotten away with the countless nefarious exploits of his youth. However, old habits die hard and to fund his new life, Turpin would often travel across the river from Yorkshire to nearby Lincolnshire to steal sheep and horses. However, the event that really sealed Turpin’s fate is when he shot a man’s cockerel supposedly after a failed hunt in 1738 resulted in a frustrated and drunken Turpin deciding to take his aggression out on the cock.

In truth, whether Turpin shot the cockerel to eat or just because he was annoyed isn’t really clear from contemporary reports from the time. All we know for sure is that the owner of the cockerel was understandably a little angry at Turpin and confronted him for the shooting. Turpin, rather than profusely apologising or offering to pay for the animal or something like that, instead decided it would be best to threaten to kill those rebuking him; they then went straight to the authorities.

After being placed under arrest, the authorities became deeply suspicious about their town’s relatively new resident, since they had no record of his existence before a year previous and there was some suspicion on how exactly he actually made a living.

Under questioning, Turpin stuck to his story and claimed he was a down on his luck butcher from Lincolnshire called John Palmer, who now dealt in horse trading. When the Justices of the Peace questioning Turpin asked their colleagues in Lincolnshire if they’d ever heard of John Palmer, they replied that they had, as he had spent approximately nine months there. Unfortunately for Turpin, they also noted that he was suspected of sheep and horse rustling and that he’d previous escaped custody when they tried to question him.

Realising they might be dealing with a greater crime than they’d initially suspected- killing a game cock being a relatively minor offence compared to stealing horses, which was among the close to 200 capital offences at the time in England- “Palmer” was transferred to the dungeons at York Castle on the 16th of October, 1738.

Growing increasingly desperate for character references that likely would have seen him walk free (the hard evidence against him was scant concerning the horse theft), Turpin penned a letter to his brother-in-law, Pompr Rivernall (married to Turpin’s sister, Dorothy), in the hopes of getting such references.

Unfortunately for Turpin, Pompr took one look at the handwriting on the cover of the letter and refused to pay the postage fee, supposedly stating, he “had no correspondent at York”. Exactly why Rivernall really refused the letter is a matter of some debate. There are some who believe that Rivernall really didn’t know who the letter was from or that he was too tight-fisted to fork out the sixpence necessary to receive it. Others speculate Rivernall knew that the letter was from Turpin and simply refused to pay because he was either tired of being associated with his wife’s brother or scared of getting involved in his affairs.

Whatever the reason, the letter ended up being sent back to the postmaster’s office in Saffron Walden, Essex. As fate would have it, the postmaster in Saffron Walden was none other than James Smith, the man who’d taught Turpin to read and write at the village school some two decades before.

Smith, supposedly recognising the handwriting of his most infamous student on the cover, paid the postage himself and took the letter to the local magistrate who gave him permission to open it to discern its contents, with Smith’s hope being the contents would confirm his suspicions. If confirmed, this would entitle Smith to the 200 pound reward on Turpin’s head, which is approximately £20,000 (about $27,000) today.

After discovering that, indeed, the letter did appear to be from Turpin and it had been sent from York Prison, Smith traveled to York, fingered Turpin, and collected his reward.

Although Turpin was seemingly caught because of his evidently distinctive handwriting, no known example of it has survived, meaning we actually have no real idea how Turpin’s former schoolmaster was able to recognise it after two decades. It’s very possible he simply knew the letter was to the brother-in-law of Dick Turpin, with Turpin’s whereabouts unknown, and the letter’s origin was from a place Rivernall otherwise didn’t have a correspondence. Thus, perhaps he simply suspected the letter was from Turpin in the first place, with the writing on the cover perhaps having little to do with his suspicions, despite what he said to the magistrate. Or maybe Turpin really did have quite distinct hand-writing, or distinct enough that with other suspicions Smith was able to put two and two together.

Whatever the case, though the evidence against Turpin concerning the horses he allegedly stole was scant, now that the locals knew he was the famed highwaymen, any chance of him getting off from lack of evidence went away and he was tried and convicted on several counts of horse theft.

At his trial, Turpin noted that he wasn’t given enough time to prepare a proper defence for himself and that he’d been told the trial would take place in Essex, not York, and so hadn’t bothered to get witnesses in his defence to come to York. (At the time in England, suspected criminals were not given legal counsel or representatives, and instead, lacking funds to pay for such council, had to defend themselves, including somehow organising witnesses for their defence all while sitting in prison.)

As for his execution, the city of York didn’t have an executioner. Instead, it was customary to grant a prisoner a pardon in return for their services in this role. As the fates would have it, the executioner who ended up hanging Turpin just so happened to be one of his old partners in crime, Thomas Hadfield.

Rather than go out begging for his life, Turpin spent some of his ill-gotten funds to purchase a fine set of clothes to wear to his execution, as well as hired a group of mourners to follow him to the gallows. It was also noted that he “behav’d himself with amazing assurance [and] bow’d to the spectators as he passed”.

Further, according to an issue of Gentleman’s Magazine on the day of Turpin’s hanging, “Turpin behaved in an undaunted manner; as he mounted the ladder, feeling his right leg tremble, he spoke a few words to the topsman, then threw himself off, and expir’d in five minutes.”

And so it was that on April 7, 1739 at the age of around 32, the infamous highwayman Dick Turpin ceased to be. He was laid to rest in the grounds of nearby St George’s church.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Famed Bankrobber John Dillinger Once was a Professional Baseball Player

- From a Life of Crime to One of the Most Prolific Actors of All Time- Danny Trejo’s Prison Break

- The London Garrotting Panic of the Mid-19th Century

- “The Queen of Thieves”- The Story of Criminal Mastermind, Ma’ Mandelbaum

- The Man Who Survived Three Consecutive Hangings

Bonus Facts:

- While awaiting his execution, Turpin’s infamy as a highwayman saw him become one of York prison’s most famous residents with people coming from all around to see him. Supposedly the guard outside of his cell made a small fortune charging people to visit Turpin, some of whom were reportedly women who wanted to get to know the bad-boy Turpin in a rather intimate fashion.

- After being killed, Turpin’s body was briefly stolen (grave robbing being a common practice at the time as a way for those in the medical profession to acquire bodies to practice on) before being recovered by an angry mob who’d set out to find the thieves. Because of this, there are some who believe that the body that was eventually put back into Turpin’s grave may not have actually been his.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|