How Does GPS Actually Work and Why Many GPS Devices are About to Stop Working

Developed over the course of decades, GPS has become far more ubiquitous than most people realize. Not just for navigation, its extreme accuracy in time keeping (+/- 10 billionths of a second) has been used by countless businesses the world over for everything from aiding in power grid management to helping manage stock market and other banking transactions. The GPS system essentially allows for companies to have near atomic clock level precision in their systems, including easy time synchronization across the globe, without actually needing to have an atomic clock or come up with their own systems for global synchronization. The problem is that, owing to a quirk of the original specifications, on April 6, 2019 many GPS receivers are about to stop working correctly unless the firmware for them is updated promptly. So what’s going on here, how exactly does the GPS system work, and who first got the idea for such a system?

Developed over the course of decades, GPS has become far more ubiquitous than most people realize. Not just for navigation, its extreme accuracy in time keeping (+/- 10 billionths of a second) has been used by countless businesses the world over for everything from aiding in power grid management to helping manage stock market and other banking transactions. The GPS system essentially allows for companies to have near atomic clock level precision in their systems, including easy time synchronization across the globe, without actually needing to have an atomic clock or come up with their own systems for global synchronization. The problem is that, owing to a quirk of the original specifications, on April 6, 2019 many GPS receivers are about to stop working correctly unless the firmware for them is updated promptly. So what’s going on here, how exactly does the GPS system work, and who first got the idea for such a system?

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik. As you might imagine, this tiny satellite, along with subsequent satellites in the line, were closely monitored by scientists the world over. Most pertinent to the topic at hand today were two physicists at Johns Hopkins University named William Guier and George Weiffenbach.

As they studied the orbits and signals coming from the Sputnik satellites the pair realized that, thanks to how fast the satellites were going and the nature of their broadcasts, they could use the Doppler shift of the signal to very accurately determine the satellite’s position.

Not long after, one Frank McClure, also of Johns Hopkins University, asked the pair to study whether it would be possible to do this the other way around. They soon found that, indeed, using the satellite’s known orbit and studying the signal from it as it moved, the observer on the ground could in a relatively short time span determine their own location.

This got the wheels turning.

Various systems were proposed and, in some cases, developed. Most notable to the eventual evolution of GPS was the Navy’s Navigation Satellite System (also known as the Navy Transit Program), which was up and running fully by 1964. This system could, in theory, tell a submarine or ship crew where they were within about 25 meters, though location could only be updated about once per hour and took about 10-15 minutes to acquire. Further, if the ship was moving, the precision would be off by about one nautical mile per 5 knots of speed.

Another critical system to the ultimate development of GPS was known as Timation, which initially used quartz clocks synchronized on the ground and on the satellites as a key component of how the system determined where the ground observer was located. However, with such relatively imprecise clocks, the first tests resulted in an accuracy of only about 0.3 nautical miles and took about 15 minutes of receiving data to nail down that location. Subsequent advancements in Timation improved things, even testing using an atomic clock for increased accuracy. But Timation was about to go the way of the Dodo.

By the early 1970s, the Navigation System Using Timing and Ranging (Navstar, eventually Navstar-GPS) was proposed, essentially combining elements from systems like Transit, Timation, and a few other similar systems in an attempt to make a better system from what was learned in those projects.

Fast-forward to 1983 and while the U.S. didn’t yet have a fully operational GPS system, the first prototype satellites were up and the system was being slowly tested and implemented. It was at this point that Korean Air Lines Flight 007, which originally departed from New York, refueled and took off from Anchorage, Alaska, bound for Seoul, South Korea.

What does this have to do with ubiquitous GPS as we know it today?

On its way, the pilots had an unnoticed autopilot issue, resulting in them unknowingly straying into Soviet airspace.

Convinced the passenger plane was actually a spy plane, the Soviets launched Su-15 jets to intercept the (apparently) most poorly crafted spy plane in history- the old “It’s so overt, it’s covert” approach to spying.

Warning shots were fired, though the pilot who did it stated in a later interview, “I fired four bursts, more than 200 rounds. For all the good it did. After all, I was loaded with armor piercing shells, not incendiary shells. It’s doubtful whether anyone could see them.”

Not long after, the pilots of Korean Air 007 called Tokyo Area Control Center, requesting to climb to Flight Level 350 (35,000 feet) from Flight Level 330 (33,000 feet). This resulted in the aircraft slowing below the speed the tracking high speed interceptors normally operated at, and thus, them blowing right by the plane. This was interpreted as an evasive maneuver, even though it was actually just done for fuel economy reasons.

A heated debate among the Soviet brass ensued over whether more time should be taken to identify the plane in case it was simply a passenger airliner as it appeared. But as it was about to fly into international waters, and may in fact already have been at that point, the decision was made to shoot first and ask questions later.

The attacking pilot described what happened next:

“Destroy the target…!” That was easy to say. But how? With shells? I had already expended 243 rounds. Ram it? I had always thought of that as poor taste. Ramming is the last resort. Just in case, I had already completed my turn and was coming down on top of him. Then, I had an idea. I dropped below him about two thousand metres… afterburners. Switched on the missiles and brought the nose up sharply. Success! I have a lock on.

Two missiles were fired and exploded near the Boeing plane causing significant damage, though in a testament to how safe commercial airplanes typically are, the pilots were able to regain control over the aircraft, even for a time able to maintain level and stable flight. However, they eventually found themselves in a slow spiral which ended in a crash killing all 269 aboard.

As a direct result of this tragedy, President Ronald Reagan announced on September 16, 1983 that the GPS system that had previously been intended for U.S. military use only would now be made available for everyone to use, with the initial idea being the numerous safety benefits such a system would have in civil aviation over using then available navigation tools.

This brings us to how exactly the GPS system works in the first place. Amazingly complex on some levels, the actual nuts and bolts of the system are relatively straightforward to understand.

This brings us to how exactly the GPS system works in the first place. Amazingly complex on some levels, the actual nuts and bolts of the system are relatively straightforward to understand.

To begin with, consider what happens if you’re standing in an unknown location and you ask someone where you are. They reply simply- “You are 212 miles from Seattle, Washington.”

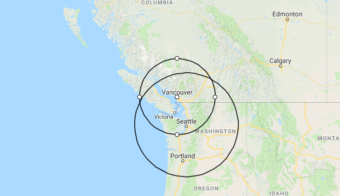

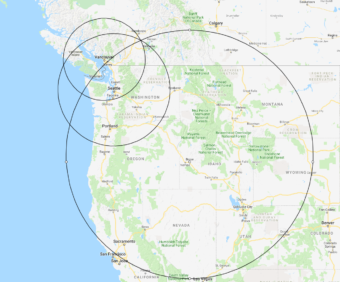

You now can draw a circle on a map with radius 212 miles from Seattle. Assuming the person giving you that information is correct, you know you’re somewhere along that circular line.

Not super helpful at this point by itself, you then ask someone else, and they say, “You are 150 miles from Vancouver BC.” Now you’re getting somewhere. When you draw that circle on the map, you’ll see it intersects at two points. You are standing on one of those two points. Noticing that you are not, in fact, floating in the ocean, you could at this point deduce which point you are on, but work with us here people.

Not super helpful at this point by itself, you then ask someone else, and they say, “You are 150 miles from Vancouver BC.” Now you’re getting somewhere. When you draw that circle on the map, you’ll see it intersects at two points. You are standing on one of those two points. Noticing that you are not, in fact, floating in the ocean, you could at this point deduce which point you are on, but work with us here people.

Instead of making such an assumption, you decide your senses are never to be trusted and, after all, Jesus stood on water, so why not you? Thus, you ask a third person- they say, “You are 500 miles from Boise, Idaho.” That circle drawn, you now know exactly where you are in two dimensional space. Near Kamloops, Canada, as it turns out.

This is more or less what’s happening with GPS, except in the case of GPS you need to think in terms of 3D spheres instead of 2D circles. Further, how the system tells you your exact distance from a reference point, in this case each of the satellites, is via transmitting the satellites’ exact locations in orbit and a timestamp of the exact time when said transmission was sent. This time is synchronized across the various satellites in the GPS constellation.

This is more or less what’s happening with GPS, except in the case of GPS you need to think in terms of 3D spheres instead of 2D circles. Further, how the system tells you your exact distance from a reference point, in this case each of the satellites, is via transmitting the satellites’ exact locations in orbit and a timestamp of the exact time when said transmission was sent. This time is synchronized across the various satellites in the GPS constellation.

The receiver then subtracts the current known time upon receiving the data from that transmission time to determine the time it took for that signal to be transmitted from the satellites to its location.

Combining that with the known satellite locations and the known speed of light with which the radio signal was propagated, it can then crunch the numbers to determine with remarkable accuracy its location, with margins of error owing to things like the ionosphere interfering with the propagation of the signal, and various other real world factors such as this potentially throwing things off a little.

Even with these potential issues, however, the latest generation of the GPS system can, in theory, pinpoint your location within about a foot or about 30 centimeters.

You may have spotted a problem here, however. While the GPS satellites are using extremely precise and synchronized atomic clocks, the GPS system in your car, for example, has no such synchronized atomic clock. So how does it accurately determine how long it took for the signal to get from the satellite to itself?

It simply uses at least four, instead of three, satellites, giving it the extra data point it needs to solve the necessary equations to get the appropriate missing time variable. In a nutshell, there is only one point in time that will match the edge of all four spheres intersecting in one point in space on Earth. Thus, once the variables are solved for, the receiver can adjust its own time keeping appropriately to be almost perfectly synchronized, at least momentarily, with the much more precise GPS atomic clocks. In some sense, this makes GPS something of a 4D system, in that, with it, you can know your precise point in not only space, but time.

By continually updating its own internal clock in this way, the receiver on the ground ends up being nearly as accurate as an atomic clock and is a time keeping device that is then almost perfectly synchronized with other such receivers across the globe, all for almost no cost at all to the end users because the U.S. government is footing the bill for all the expensive bits of the system and maintaining it.

Speaking of that maintanence, another problem you may have spotted is that various factors can, and do, continually move the GPS satellites off their original orbits. So how is this accounted for?

Tracking stations on Earth continually monitor the exact orbits of the various GPS satellites, with this information, along with any needed time corrections to account for things like Relatively, frequently updated in the GPS almanac and ephemeris. These two data sets are used for holding satellite status and positional information and are regularly broadcast to receivers, which is how said receivers know exact positions of the satellites in the first place.

The satellites themselves can also have their orbits adjusted if necessary, with this process simply being to mark the satellite as “unhealthy” so receivers will ignore it, then move it to its new position, track that orbit, and once that is accurately known, update the almanac and ephemeris and mark the satellite as “healthy” again.

So that’s more or less how GPS came to be and how it works at a high level. What about the part where we said many GPS devices may potentially stop working very soon if not updated?

Near the turn of the century something happened that had never happened before in the GPS world- dubbed a “dress rehearsal for the Y2K bug”. You see, as a part of the time stamp sent by the GPS satellites, there is something known as the Week Number- literally just the number of weeks that have passed since an epoch, originally set to January 6, 1980. Along with this Week Number the number of seconds since midnight on the previous Saturday evening is sent, thus allowing the GPS receiver to calculate the exact date.

So what’s the problem with this? It turns out every 1024 weeks (about every 19 years and 8 months) from the epoch, the number rolls back to 0 owing to this integer information being in 10 bit format.

Thus, when this happens, any GPS receiver that doesn’t account for the Week Number Rollover, will likely stop functioning correctly, though the nature of the malfunction varies from vendor to vendor and device, depending on how said vendor implemented their system.

For some, the bug might manifest as a simple benign date reporting error. For others, such a date reporting error might mean everything from incorrect positioning to even a full system crash.

If you’ve done the math, you’ve probably deduced that this issue first popped up in August of 1999, only about four years after the GPS system itself was fully operational.

At this point, of course, GPS wasn’t something that was so ubiquitously depended on as it is today, with only 10-15 million GPS receivers in use worldwide in 1999 according to a 1999 report by the the United States Department of Commerce’s Office of Telecommunications. Today, of course, that number is in the billions of devices.

Thankfully, when the next Week Number Rollover event happens on April 6, 2019, it would seem most companies that rely on GPS for critical systems, like airlines, banking institutions, cell networks, power grids, etc., have already taken the necessary steps to account for the problem.

The more realistic problems with this second Week Number Rollover event will probably mostly occur at the consumer level, as most people simply are not aware of the issue at all.

Thankfully, if you’ve updated your firmware on your GPS device recently or simply own a GPS device purchased in the last few years, you’re probably going to be fine here.

However, should you own a GPS device that is several years old, that may not be the case and you’ll most definitely want to go to the manufacturer’s website and download any relevant updates before the second GPS epoch.

That public service announcement out of the way, if you’re now wondering why somebody doesn’t just change the specification altogether to stop using a 10 bit Week Number, well, you’re not the first to think of this. Under the latest GPS interface specifications, a 13 bit Week Number is now used, meaning in newer devices that support this, the issue won’t come up again for about a century and a half. As the machines are bound to rise up and enslave humanity long before that occurs, that’s really their issue to solve at that point.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Who Invented the Internet?

- Who Invented the Computer Mouse?

- That Time the British Developed a Chicken Heated Nuclear Bomb

- For Nearly Two Decades the Nuclear Launch Code at all Minuteman Silos in the United States Was 00000000

- Vasili Arkhipov: The Man Who Saved the World

Bonus Facts:

- Ever notice that your cell phone tends to lock on to your GPS position extremely quickly, even after having been powered off for a long time? How does it do this when other GPS devices must wait to potentially receive a fresh copy of the almanac and ephemeris? It turns out cell phones tend to use something called Assisted GPS, where rather than wait to receive that data from the currently orbiting GPS satellites, they will instead get it from a central server somewhere. The phone may also simply use its position in the cell phone network (using signals from towers around) to get an approximate location to start while it waits to acquire the signal from the GPS satellites, partially masking further delay there. Of course, assisted GPS doesn’t work if you don’t have a cell signal, and if you try to use your GPS on your phone in such a scenario you’ll find that if you turn off the GPS for a while and then later turn it back on, it will take a while to acquire a signal like any other GPS device.

- Starting just before the first Gulf War, the military degraded the GPS signal for civilian use in order to keep the full accuracy of the system as a U.S. military advantage. However, in May of 2000, this policy was reversed by President Bill Clinton and civilian GPS got approximately ten times more accurate basically overnight.

- The military also created the ability to selectively stop others from using GPS at all, as India discovered thanks to the Kargil conflict with Pakistan in 1999. During the conflict, the U.S. blocked access to the GPS system from India owing to, at the time, better longstanding relations between the U.S. and Pakistan than the U.S. had with India. Thus, the U.S. didn’t want to seem like it was helping India in the war.

- Roger L Easten

- GPS 2019

- Bradford Parkinson

- How GPS Works

- Ivan A Getting

- Timing Critical Rollover

- GPS Rollover- What You Need to Know

- Transit Satellite

- Origins of GPS

- Korean Air Lines Flight 007

- Phasor Measurement Unit

- GPS Block III

- Worse Than Y2K

- WNRO

- Week Number Rollover

- Who Invented the GPS System?

- Father of GPS Dies

- A Brief History of GPS

- How GPS Works

- How GPS Works

- How Does GPS Work?

- GPS Satelites

- How Does GPS Work

- Global Positioning System

- GPS Rollover Week

- Why Didn’t the U.S. Let India Access GPS During the Kargil War?

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

GPS is very useful, especially to the military, and is under USA control. Naturally other countries want the benefits of GPS but don’t want to risk the USA removing those benefits. So there are other GPS-like systems, which are technically redundant (they provide nothing not already available for free from GPS) but politically very much not redundant.

Russia has GLONASS (fully operational), the EU has Galileo (I think operational but not fully operational until 2020), China has BeiDou-2 which is I think regionally fully operational and will have full global coverage in 2020. In addition, China, India and Japan have regional systems which cover large parts of the Earth near their parent countries, but are not global.

I apologise for any errors, as I am not an expert in this.

FYI: remember reading that the first use of Military GPS was to defeat the Iraqis in Desert storm . The sandstorms were so dense that Iraqi Troops were blind and could not move. The US troops were blind too but able to move behind the Iraqis and flank them from the rear using GPS to navigate.

The article failed to mention who actually operates the GPS constellation. Part of Air Force Space Command (AFSPC), the 50th Space Wing at Schreiver AFB, Colorado places the GPS satellites in their proper orbits following launch, operates, conducts telemetry, keeps them functioning properly and disposes of the satellites at their end of life.