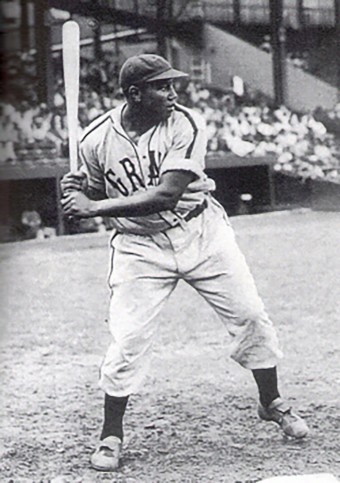

“The Black Babe Ruth”

It is undisputed that Josh Gibson was the greatest position player in Negro League history. He could field, throw, catch, and most of all, he could hit. His power was legendary. It was claimed by Chicago American Giants infielder Jack Marshall that Gibson hit a ball out of Yankee Stadium in 1934, in the history of the stadium the only player to ever do that, if true. Though his statistics were often not officially kept, it is also thought that he hit more home runs than Barry Bonds, baseball’s current home run king, in far fewer at-bats. He did all of this hitting while fielding the most physically demanding position on the diamond – catcher, which has been proven to diminish a hitter’s offensive output due to extra wear and tear on their bodies over other positions.

It is undisputed that Josh Gibson was the greatest position player in Negro League history. He could field, throw, catch, and most of all, he could hit. His power was legendary. It was claimed by Chicago American Giants infielder Jack Marshall that Gibson hit a ball out of Yankee Stadium in 1934, in the history of the stadium the only player to ever do that, if true. Though his statistics were often not officially kept, it is also thought that he hit more home runs than Barry Bonds, baseball’s current home run king, in far fewer at-bats. He did all of this hitting while fielding the most physically demanding position on the diamond – catcher, which has been proven to diminish a hitter’s offensive output due to extra wear and tear on their bodies over other positions.

When baseball was finally ready to integrate in the mid-1940s, Gibson was reaching the twilight years of a baseball player’s career- his mid-30s. But even then, if he had gotten to the Majors, given the numbers he was still putting up, he likely would have been one of the best hitters in the Major Leagues, slamming home runs out of ballparks across the country. As Larry Dobby, the second person to break the color barrier said, “One of the things that was disappointing and disheartening to a lot of the black players at the time was that Jack [Robinson] was not the best player. The best was Josh Gibson.”

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson would break the color barrier in the Major Leagues. Unfortunately, the baseball world would not get to see Gibson follow, as he died shortly before on January 20, 1947, at the tragically young age of 35. This is the story of the greatest ball player that few got to see play.

Joshua Gibson was (reportedly) born in Buena Vista, Georgia four days before Christmas in 1911. At that time, Jim Crow laws were firmly entrenched in the South, allowing for the treatment of African-Americans as second-class citizens. In an attempt to secure a better life for his family, Josh’s father, Mark, migrated north, to Pittsburgh. He got a job at Carnegie-Illinois Steel Company. It took several years, but the Gibson family was eventually united in 1924, when Josh was 13 years old. Later, Gibson would say, “The greatest gift Dad gave me was to get me out of the South.”

Josh attended school, but immediately afterwards, he would go work at the same steel company as his father. He also played sports and was very good. As a sixteen year old, he was recruited by the local Gimbels department store to play for their team, but there was a rule that every player had to work for the store. So, he got a second job as an elevator operator.

The Gimbels’ team was part of the All-Negro Greater Pittsburgh Industrial League, which included other teams like Garfield Steel, Pittsburgh Railways, and Pittsburgh Screw and Bolt. Often, the games would be more popular than the Homestead Grays‘, the local Negro League team. Due to this, Gibson started to become a local star. Additionally, gamblers started to find their way to the games, betting large sums of money on the teams. While there is no evidence that Gibson benefited financially from this, at least directly, it did pour money and attention into a relatively small local Pittsburgh league and helped expose a wider audience to Gibson.

There are a few different stories on how Gibson started playing in the Negro Leagues, which one, if any, are totally accurate isn’t known. One story tells how during a night game between the Grays and Kansas City Monarchs in 1930 under Pittsburgh’s first portable lights, the Grays’ catcher broke his hand. Down a catcher, Manager Judy Johnson went into the stands and saw Gibson. Knowing who he was, he gave him a uniform and told him to play. Gibson played and the Grays officially signed him the next day. The next year, according to this story, he joined the Pittsburgh Crawfords.

The other story isn’t much of a story, but speaks to how the Pittsburgh Crawfords had been scouting him for years. The Crawfords’ main benefactor was an African-American mobster named Gus Greenlee and he wanted Gibson on his team. And what Greenlee wanted, he got. So, Gibson ended up on the Crawfords. What isn’t disputed is what happened next – Josh Gibson became one of the greatest hitters in the world.

Before Gibson literally hit it big, tragedy struck. His newly-wed wife Helen, who would be the only woman he would marry, died in 1930 while giving birth to twins. Unable to deal with the grief, he left his kids with his in-laws, rarely seeing them as they grew up. He threw himself into baseball and the hard lifestyle that can come with it.

By 1931, the Pittsburgh Crawfords were starting to assemble one heck of a team. During the summer, Greenlee purchased the contract of Leroy “Satchel” Paige for two hundred and fifty dollars (about four thousand dollars today). Paige would go on to be the perfect complement to Gibson, as a flame-throwing pitcher with a fiery personality to boot. Gibson was quiet, funny, and loved to make friends, while Paige was loud, showy, and loved to needle opponents. They were both among the greatest ball players in the history of the game.

In 1932, Greenlee Field was completed and was immediately the best ballpark in the Negro Leagues. Between Gibson and Paige, the sparkling new field, and Greenlee’s reputation, the Crawfords were able to put together a team unmatched in baseball talent. Future Hall of Famers Judy Johnson, Oscar Charleston, Paige, Gibson, and Cool “Papa” Bell played ball for the Crawfords that year. In 1933, Greenless founded the Negro National League and Crawfords were a charter member. While no official stats were recorded, from what evidence is available, it is generally believed that Gibson hit about 60 home runs that year, including several that cleared Greenlee Field completely and one estimated to have gone about 520 feet.

It should be noted, though, that the Negro League season was much shorter than the Major League season (usually around 60 games) to allow the teams to make money via barnstorming, generally playing about 2/3 of their games each year against inferior teams than one would find in the Negro Leagues or Major Leagues. However, via painstakingly going through box scores from old newspapers and other such records, it’s generally thought that when playing against Negro League teams during the regular season, Gibson averaged about 1 home run every 15.9 at bats, which would have put him in the top 10 in Major League history. The Major League Baseball Hall of Fame also credits Gibson with a lifetime .359 batting average, as well as around 800 home runs total (both in the Negro League games and their barnstorming tours).

In any event, even though Gibson was barely 23 years old in 1934 and dealing with the rigors of playing behind the plate, he was the best hitter in the Negro Leagues.

Standing at six foot one and a stocky 215 pounds, he was a bulky catcher. He actually started his career as a third basemen, but his lumbering frame was a tad slow for the hot corner. Greenlee and his coaches moved him to catcher because he was so big, “No one dared to steal home on Gibson.” Hitting at the plate, he was just as imposing. Said fellow Negro League ballplayer and Hall of Famer Monte Irving, “He’s the best hitter I’ve ever seen. He would come to the plate and you would be in awe.”

From 1930 to 1940, Gibson played on the Pittsburgh Crawfords and then the Homestead Grays, smashing home runs and leaving a lasting impression on fans of all colors. Said legendary Major League Baseball pitcher Walter Johnson, “There is a catcher that any big league club would like to buy for two-hundred thousand dollars. He can do everything. He hits the ball a mile, catches so easily he might as well be in a rocking chair, throws like a bullet.” He was nicknamed the “Black Babe Ruth,” though many thought Babe Ruth should have been called the “White Josh Gibson.”

In 1940, with the Majors still not opening its ranks to everyone, Gibson and several other famed Negro League players went to Mexico to play ball down south. You see, the Mexican and the Puerto Rican Leagues were willing to pay these stars a lot more money than they got in the Negro Leagues. However, in 1942, Gibson returned to the Negro Leagues because he was sued by the Homestead Gray’s owner for breaking a contract. He again led the Negro Leagues in home runs.

Early the next year, Gibson started to succumb to the recurring intense headaches that had been plaguing him his whole adult life. He attempted to play through it, though it took its toll on him, as Gibson reportedly “drank his way through it” and developed an alcohol problem as a result.

Sometime around 1944 or 1945, the cause of his headaches was discovered- he had a brain tumor. Shortly after being diagnosed, this put him in a coma. He did awake from his coma, only to refuse the doctors’ order of an operation.

On January 20, 1947, Josh Gibson died at the very young age of 35. As mentioned, on April 15th that same year, Jackie Robinson played his first game for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

It would take a whole book to get to all the interesting stories and quotes about Josh Gibson, but teammate and friend Satchel Paige probably summed up Gibson’s baseball prowess best when he said, “You look for his weakness and while you’re lookin’ for it, he’s liable to hit 45 home runs.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Babe Ruth – The Ladies’ Man

- The 17 Year Old Girl Who Struck Out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig Back to Back

- Jackie Robinson was Not the First African American to Play Major League Baseball

- The Forgotten Hero: Larry Doby

- The First Person to Play for Both Baseball’s National League and American League All-Star Teams was a Woman: Lizzie “The Queen of Baseball” Murphy

| Share the Knowledge! |

|