The Bum Brigade

On October 29, 1929, on what would become known as “Black Tuesday,” the stock market crashed. In one terrible day, the market lost fourteen billion dollars (about $188B today), signaling the beginning of the (roughly) ten-year-long Great Depression, with most of the last vestiges of the downturn only ceasing around 1939 due to the onset of World War II.

Just as the effects of an economic downturn spread from Wall Street to the farmers of rural America, another major problem arose: a severe drought struck middle America. Starting in 1931, the drought, coupled with poor farming practices, caused hellacious dust storms to envelope much of America’s midwest. Through much of the 1930s, these storms ravaged land, crops, and topsoil, making it impossible for many crops to grow and the farmer to earn a living.

The worst of it happened on what was supposed to be a beautiful spring Sunday. On April 14, 1935, later called “Black Sunday,” a dust storm darkened the sky from northern Canada to southern Texas. The next day, when reporters wrote about the incident, they made references to the “dust bowl,” including this in the Associated Press, “Three little words… rule life in the dust bowl of the continent – ‘if it rains’.” From that moment forward, “Dust Bowl” was used to describe the panhandle of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and parts of New Mexico.

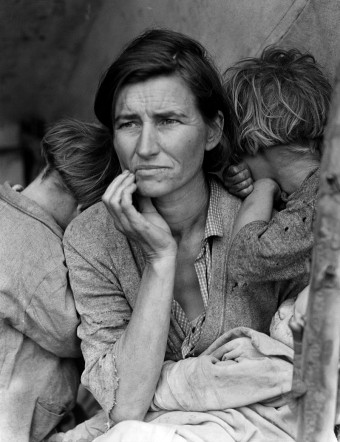

Between the dust storms, the economic downturn, and a belief in a better life, many farmers and families pulled up their stakes and left the Dust Bowl. Piling into their wagons and cars, they looked west, much like their ancestors from a hundred years before during the California Gold Rush, and headed to the supposedly work-paved roads of California. With nearly 200,000 people (about 1 in 600 in the U.S.) making their move, it was one of the greatest mass exoduses in American history.

Many traveled via the “mother road” Route 66, the recently constructed interstate highway that connected Chicago to Los Angeles and everything in between. To this day, Route 66 remains probably the most famous road in America. From 1931 until late 1935, dust bowl refugees, often derogatorily called “Okies” despite the fact that they weren’t all from Oklahoma, poured into California, mostly into the growing metropolis of Los Angeles, that had just a couple decades before seen a huge boost thanks to the mass-exodus from San Francisco after approximately 80% of the city was destroyed after the Great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906. (See: When San Francisco was Almost Wiped Off the Map)

During the Dust Bowl exodus, it was estimated at the time that nearly a thousand people per day crossed into the city’s borders. But Los Angeles was also struggling due to the Depression. Jobs, thought plentiful by the migrants, were actually not. Even native Angelenos had a hard time finding work, much less with a massive number of new additions joining them. This also allowed employers to hire the desperate workers for lower wages, further angering locals. With these issues reaching a head, the Jones-Redwine Bill was proposed in the California State Assembly in May 1935 which would, “prohibit all paupers, vagabonds, indigent persons and persons likely to become public charges, and all persons affected with a contagious or infectious disease from entering California until July 1, 1939.” It didn’t pass, but it was clear something had to be done.

During the Dust Bowl exodus, it was estimated at the time that nearly a thousand people per day crossed into the city’s borders. But Los Angeles was also struggling due to the Depression. Jobs, thought plentiful by the migrants, were actually not. Even native Angelenos had a hard time finding work, much less with a massive number of new additions joining them. This also allowed employers to hire the desperate workers for lower wages, further angering locals. With these issues reaching a head, the Jones-Redwine Bill was proposed in the California State Assembly in May 1935 which would, “prohibit all paupers, vagabonds, indigent persons and persons likely to become public charges, and all persons affected with a contagious or infectious disease from entering California until July 1, 1939.” It didn’t pass, but it was clear something had to be done.

In the August 24, 1935 edition of the Los Angeles Herald Express, an article ran warning refugees not to come to California. The first line read,

Indigent transients heading for California today were warned by H. A. Carleton, director of the Federal Transient Service, “to stay away from California… California is carrying approximately 7 percent of the entire national relief load, one of the heaviest of any State in the Union. A large part of this load was occasioned by thousands of penniless families from other States who have literally overrun California.”

Still, the mass migration didn’t stop, that is until someone took this task, and the law, into their own hands.

The Los Angeles police chief at the time was James “Two-Gun” Davis, who already earned a reputation as being no-nonsense and corrupt. He was the man behind the “Gun Squad,” where he allowed select officers to take down gangsters by any means necessary, even illegally. He once said, “hold court on gunmen in the Los Angeles streets; I want them brought in dead, not alive and will reprimand any officer who shows the least mercy to a criminal.” Point being, when he wanted something done, he did it and didn’t care at all if it was against the law he had sworn to protect.

Beginning in November of 1935, he sent 136 LAPD officers to 16 different California entry points, ones that bordered Arizona, Oregon, and Nevada with orders to turn back any incomers with “no visible means of support.” It was a harsh way to deal with the crisis and one that was not legal.

Beginning in November of 1935, he sent 136 LAPD officers to 16 different California entry points, ones that bordered Arizona, Oregon, and Nevada with orders to turn back any incomers with “no visible means of support.” It was a harsh way to deal with the crisis and one that was not legal.

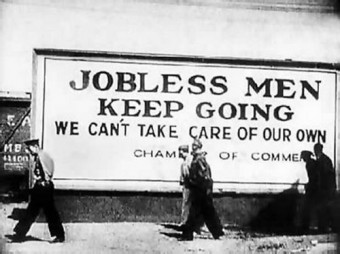

Davis claimed he was simply upholding California’s 1933 Indigent Act which made it illegal for an indigent (poor and needy) persons to enter the state. Additionally, Davis had support from state relief agencies, who couldn’t deal with the influx; many public officials; the railroads (many migrants were also entering via train); and the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, who feared that, “street beggars were ‘a bad advertisement’ for Los Angeles.” Even the Los Angeles Times supported Chief Davis. They compared him to Queen Elizabeth when she declared “a war on bums.”

By December, these officers had become known as the “Bum Brigade.” They were given specific orders to search all incoming cars, wagons, and trains. Those who had “no means of support,” no train ticket, or were under suspicion for “vagrancy” were told to either leave the state or face jail time. Many choose to turn around and leave.

By the middle of February, city officials finally spoke up, including the Attorney General of California, Ulysses S. Webb, who said that not allowing American citizens to cross state borders was unconstitutional. California governor Frank Merriam didn’t disagree, but knew how powerful the city of Los Angeles was, “I guess Los Angeles can do it, its city’s boundaries almost go that far.”

April brought the ACLU lawsuits and the ending of Davis’ Bum Brigade. ACLU director Ernest Besig said that LAPD officers were “conspiring to take away the civil rights of United States citizens,” and that the policies enacted were a “violation of the city charter and the state and federal constitutions.” Other officials questioned why immense city funds were being used for this far-flung project.

The officials were eventually called home to LA, but Davis claimed victory. He stated that over 11,000 people were turned away which caused an “absence of a seasonal crime wave in Los Angeles.” He estimated that over four million dollars were saved on policing “thieves and thugs” and paying out welfare payments.

In 1937, the Resettlement Administration (one of FDR’s New Deal agencies) began building migrant camps along California’s border to temporarily house those trying to enter the state. Eventually, the Farm Security Administration, whose job was to combat rural poverty during the Depression, took this over. This was, at least, a more practical, if not slightly more humane way of dealing with the migrant problem.

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor bringing America into World War II officially and, most historians consider, out of the Great Depression. War time production immediately took hold of the country and America began its rise into the prosperous 1950s.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Scrabble and the Great Depression

- The Famous “HOLLYWOOD” Sign Originally Read “HOLLYWOODLAND” and Was Lit By About 4,000 Light Bulbs Embedded in the Letters

- The “Luckiest” Building in Silicon Valley

- Seattle Doesn’t Get That Much Rain

- What Happened to Howard Hughes’ Money After He Died

- The Bum Blockade: Los Angeles and the Great Depression – Chapman University Historical Review

- Mass Exodus From the Plains – PBS

- Homelessness: A Documentary and Reference Guide By Neil L. Shumsky

- The Bum Blockade – Legends of America

- Wall Street Crash of 1929 – Wikipedia

- The “Black Sunday” Dust Storm of 14 April 1935 – The National Weather Service

- The LAPD: 1926-1950 – The Los Angeles Police Department

- Farm Security Administration – Wikipedia

- Route 66Exhibit – The Autry Museum

| Share the Knowledge! |

|