The First Gas/Electric Hybrid Vehicle was Invented in 1900

Today I found out the first gas/electric hybrid vehicle was invented in 1900.

Today I found out the first gas/electric hybrid vehicle was invented in 1900.

While hybrid and electric cars are often touted by the media and automobile companies as the wave of the future, in fact, we’re more just re-hashing the wave of the past with them, but with updated technologies.

Before gas cars ruled the road, first steam, then electric cars were king, with a few manufacturers also coming up with hybrid gas/electric cars to get around the limited range and high weight of electric vehicles from the large number of battery cells needed. Besides causing problems while climbing hills and the like, this high amount of weight particularly caused issues for the tires of the day, which still used soft white rubber without carbon black added to significantly increase certain desirable qualities of the tires over white tires. (more on this here)

Enter Austrian Ferdinand Porsche. Porsche had little formal engineering training outside of attending occasional classes at the Imperial Technical School in Reichenberg and later sitting in on certain classes in Vienna after getting a job at the Béla Egger Electrical Company.

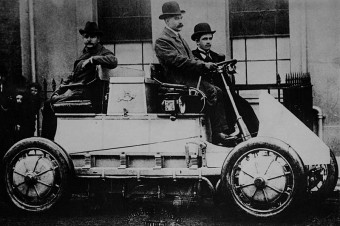

This lack of formal training didn’t stop him from designing the “System Lohner-Porsche” at the age of 23 in 1898. This car would not only be the world’s first front wheel drive vehicle, but would also be the basis for the world’s first gas/electric hybrid. The Lohner-Porsche had two in-wheel electric motors and was powered by on-board batteries. They later added two more in-wheel motors making it one of the first four wheel drive cars in existence and the first to have a four wheel breaking system.

Because the motors for turning the wheels where embedded in the front wheel hubs themselves, this significantly increased the efficiency of the system by reducing mechanical friction- eliminating the need for a gearbox, clutch, drive shaft, etc.

Porsche followed up the Lohner-Porsche with the world’s first fully functional gas/electric hybrid vehicle, the Semper Vivus (“Always Alive”). As mentioned, this car was based on the Lohner-Porsche car design, but reduced the number of battery cells from 74 to 44 and added two internal De-Dion-Bouton 2.5 HP combustion engines to power two generators, producing a total of 3.68 kw.

This first hybrid car system worked by having the generators send electricity directly to the electric motors with any excess being used to charge the batteries. This car also had the capability of running just off batteries with the combustion engines turned off, if the driver so chose.

Yet another innovation with the Semper Vivus was that it allowed the gas powered motors to be started by the electric motors by simply reversing the polarity and running it off the batteries for a couple seconds in reverse. Alternatively, the gas powered motors could be started the “normal” way, by hand cranking them.

The Semper Vivus still had a few problems. It was fairly bare bones, including having exposed gas powered engines, no shocks on the rear axle, and suffered from a problem of dirt being continually thrown up into various parts of the system, which often resulted in it temporarily breaking down. In addition to that, it didn’t really solve the problem of weight as it ended up being 70 kg heavier than the original Lohner-Porsche, despite the significant reduction in batteries. Nevertheless, the Semper Vivus is estimated to have been capable of a top speed of 22 mph with a range of about 124 miles on a full tank, both of which were very good for the day.

Porsche followed the Semper Vivus up with a production capable hybrid, the Lohner-Porsche Mixte in 1901. The Mixte drastically cut back on the number of battery cells and introduced a much more powerful motor (25 hp), among many other significant improvements. Among its various accomplishments, the Mixte won the Exelberg Rally in 1901. (Porsche himself drove it at that rally.) And it broke the Austrian speed record, with a top speed of 60 km/h (37.2 mph), and later the four wheel version was able to get up to 112.6 km/h (70 mph).

Other improvements were made to the Mixte and numerous other hybrid cars were soon developed by various manufacturers with thousands of gas/electric hybrid and electric vehicles being sold throughout the world until Henry Ford and various other factors came into play.

Due in part to his innovative assembly line construction, by 1915 Henry Ford was able to offer his cars at a base price of around $500 a piece (equivalent to about $10,000 today), which made his cars affordable for even the non-wealthy. In contrast, at that time the average price of an electric car had steadily risen to about $1700 and hybrids were typically much more than that. This was also around the same time crude oil was discovered in Texas and Oklahoma, which drastically reduced the cost of gasoline so that it was now affordable to average consumers. Also, Charles Kettering invented the electric starter, which eliminated the need to hand crank gas powered engines. Roads began expanding, spurring the need for greater range than electrics alone could provide at the time. This was not only because of the range factor, but also because gasoline cars were now becoming significantly faster than electric cars. Hybrids could cover the distance and some were quite fast, but they were much more expensive than their non-hybrid gas powered counterparts.

Thus, by 1935 the electric and hybrid cars were officially comatose and they wouldn’t be revived until around the 1960s and then still unsuccessfully until showing promising signs of life in the last decade or so.

If you liked this article and the Bonus Facts below, you might also like:

- Robert Downey Jr. Modeled His Portrayal of Tony Stark After Elon Musk, One of the Founders of Zip2, PayPal, Tesla Motors, Solar City, and SpaceX

- Lamborghini Cars Were A Result Of A Tractor Company Owner Being Insulted by the Founder of Ferrari

- Why Some Countries Drive on the Right and Some on the Left

- In 1899 Ninety Percent of New York City’s Taxi Cabs Were Electric Vehicles

Bonus Facts:

- The first speeding infraction in the U.S. was committed by New York City taxi driver Jacob German in an electric car on May 20, 1899. German was driving his taxi at a blistering 12 miles per hour down Lexington Street in Manhattan. At that time, the speed limit was 8 miles per hour on straight-a-ways and 4 miles per hour when turning. A police officer on a bicycle observed the 26 year old Mr. German speeding and promptly arrested him and imprisoned him in the East 22nd Street station house.

- While German was the first person in the U.S. to be cited for speeding, he was not the first to receive a speeding ticket in the United States. That honor goes to Harry Myers of Dayton Ohio in 1904. Mr. Myers was also traveling 12 miles per hour when the police observed him speeding. In his case though, he wasn’t arrested, but was just issued a ticket.

- The first known speeding infraction anywhere is thought to have happened in Great Britain on January 28, 1896, around three years before Jacob German was arrested for speeding. This infraction was committed by Walter Arnold of East Peckham, Kent. Mr. Arnold was traveling in a 2 mph zone (yes, 2 mph) and was going a breakneck 8 mph. The fine he received was for 1 shilling.

- While people have been drunk “driving” horses / camels / etc. likely as long as alcohol has been brewed by man, the first person arrested for drunk driving was London cabdriver George Smith. On September 10, 1897, the intoxicated Smith crashed his taxi into the side of a building and was soon cited for drunk driving, which he was fined 25 shillings for.

- Drunk driving was not technically illegal anywhere in the United States until 1910 when New York became the first to pass laws against driving while intoxicated.

- Very shortly after Porsche put out the world’s first hybrid car, Belgian car-maker Pieper introduced what is probably the world’s second hybrid car, also made in 1900. This hybrid wasn’t nearly as impressive, in terms of innovative features, as the Semper Vivus. The Pieper primarily used a 3.5 hp gas engine for driving around, but if the car needed more power, such as while climbing a hill, the electric motor would kick in to help the combustion motor out. When extra power was not needed, the electric motor would work as a generator to re-charge the batteries, using the car’s motion to turn the electric motor.

- NASA studied the Lohner-Porsche car design as a basis for certain features of the Lunar Rover.

- One early “hybrid” of a different sort was The Woods Interurban. This was a car that ran off of gas or electric, depending on your needs at the time. What made this hybrid different from so many others was that the engine itself was designed to be easily swapped out (they advertised in under 15 minutes). Depending on your driving needs, you’d either have the electric motor in, or swap it out for the gas motor.

- In the year 1900 in the United States, of all the automobiles that were manufactured that year, 1,681 of them were steam powered followed closely by electric cars at 1,575. In third place by a good margin was gasoline cars, numbering just 936 made that year.

- Despite steam cars edging out electric cars, according to a survey done at the National Automobile Show in 1900 at the time, people strongly preferred electric cars due to how quiet and easy to use they were compared to gas and steam vehicles. Steam was the runner up, with gas not generally being liked owing to the exceptional amount of noise they made, the noxious exhaust, and the danger inherent in starting the engines by hand (this was before the electric starter).

- One of the best early steam cars was invented in 1825 by Goldsworthy Gurney. This car managed a ten hour trip covering an impressive, for the time, 85 miles. This is even more impressive considering the state of the roads at the time, where averaging 8.5 mph must have been quite jarring on the car.

-

In 1979, electrical engineer David Arthurs modified an Opel GT to be a hybrid car and was able to achieve an average of 75 mpg with typical driving use. This modified car featured a 5 hp lawn mower engine to run a 100 amp generator; it featured four 12 volt car batteries; it could run on just the batteries for short trips; it could reach top speeds of 90 mph, though only speeds of 50 mph running just off the generator itself without aid from the batteries; and as long as you weren’t trying to drive it over the mountains for a significant stretch, it had no trouble running continuously as long as it had gas. The generator was also capable of charging the batteries from 1/4 charge to near full charge in just 15 minutes. The modifications for this car cost Arthurs only $1,500 and he designed the hybrid system and built it into his car in under a month working on it in the evenings and weekends and using nothing but over the counter, commercially available parts. This hybrid car also featured regenerative braking, much like hybrid cars today use.

- In 1974, Dr. Victor Wouk and Charlie Rosen invented a gas/electric hybrid car with the prototype built from a Buick Skylark that that got about double the gas mileage of the average car on the road at the time in the United States. It also met the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s strict guidelines under the “Clean Air Act” which required a 90% reduction in hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide emissions. But thanks to the considerable efforts and influence of EPA bureaucrat Eric Stork, this car never saw the light of day despite Stork agreeing that they’d move ahead with the hybrid design if it passed. (He was convinced it wouldn’t pass. Further, he had to be forced to allow the car to be tested in the first place via pressure applied by the National Science Foundation after Stork’s continual refusals.) When it passed, Stork refused to follow through with that promise and rejected the car that met the stipulations of the Clean Air Act.

- For the rest of his life, Dr. Wouk continued to tout the benefits of hybrid cars, such as when Wouk wrote to the New York Times in 1979: “Tests on, and studies of, hybrids have shown that petroleum usage of 80 miles per gallon will be possible for normal daily driving, and 50 miles per gallon when averaged over a year…We should start a crash program to commercialize the hybrid. It would make sense because all aspects of the hybrid have been proved workable. No new technologies need be developed.” This was in stark contrast to full electric vehicles which needed, and to some extent still need, advances in technologies to make them as practical and capable as traditional non-hybrid gas powered cars.

- As to his reasons for rejecting this early Buick Skylark hybrid, Stork recently stated, “It’s just not a very practical technology for automotive. That’s why it’s going nowhere. It certainly wasn’t [going anywhere] then. Even today, it’s marginal.” Stork also said of The Clean Air Act, “I had one engineer who handled Section 212 for me. It wasn’t worth my time. It was just a nuisance. I was busy regulating the auto industry. I didn’t have time for that Christmas tree ornament.”

- After losing support from the EPA, Wouk sought out automobile manufacturers, but there was little motivation to put out such an environmental friendly and fuel efficient car as gas prices at the time were just 28 cents a gallon ($1.53 today).

- An functional replica of the Semper Vivus was recently built by a team led by Hubert Drescher in conjunction with the Porsche Museum. This is not an exact replica of the car, as the original exact schematics have not survived. In order to come up with how to build the replica as precisely true to the original as possible, the team looked over every known record and photo of the Semper Vivus in existence and weighed these against technologies available in the day to build the fully functional replica.

- History of Hybrid Cars

- Who Designed and Built the First Hybrid Car

- Riding in the World’s First Hybrid Electric Car

- Ferdinand Porsche

- Hybrid Vehicles

- Prof. Ferdinand Porsche Created the First Functional Hybrid Car

- Electric Car Conversion: The Amazing 75-MPG Hybrid Car

- Victor Wouk and The Great Hybrid Cover Up

- George Smith Gets Caught Drunk Driving

- Opel GT Image Source

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

2 comments