The Speaking Clock

The speaking clock is an idea that goes all the way back to 1933, when citizens of Paris were the recipients of the first such service. Since then, dozens of countries have implemented a similar system that the public can call to find out the exact time. In the UK, the service has a long and storied history and even today in the age of near ubiquitous smartphones and the internet it’s still called an astounding thirty million times per year.

The speaking clock is an idea that goes all the way back to 1933, when citizens of Paris were the recipients of the first such service. Since then, dozens of countries have implemented a similar system that the public can call to find out the exact time. In the UK, the service has a long and storied history and even today in the age of near ubiquitous smartphones and the internet it’s still called an astounding thirty million times per year.

Prior to the introduction of the UK speaking clock service in 1936, it’s noted that people wanting to know the time who didn’t have a clock or watch handy would simply call the exchange operator and ask, resulting in operators spending much of their time doing this, instead of routing calls. Prior to this, the somewhat official role of a person telling people the time often fell to employees of the Post Office, who would pass it on to their mail coaches who in turn would pass it on to the public when asked as they made their rounds. (For more ways people used to get the time, see: Telling Time Before Ubiquitous Clocks.)

With exchange operators being inundated with calls from people just wanting to know the time, it was evident from almost the moment telephones were first introduced and made available to the British public in the last years of the 19th century that an automated speaking clock system was needed. Unfortunately, the technology to record human voices wasn’t widely commercially available until around the mid-1920s. Even then, it would take until the mid-1930s for the Post Office, who controlled the telephone system in the UK at the time, to begin designing a machine that would accurately tell you the time audibly.

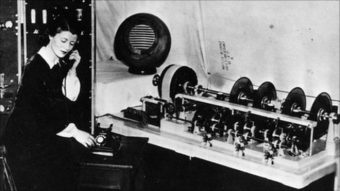

The speaking clock machine eventually constructed by the Post Office was relatively large and contained “state of the art” technology including using several electric motors, glass discs, various valves, and photocells. This system was evidently good enough that the service wasn’t upgraded until 1963, nearly three decades after it was originally introduced.

With the system designed, a voice was needed. As such the Post Office held a competition to “the girl with the golden voice”. No men were considered for the role as the telephone orientated jobs were still seen as a strictly female gendered profession back then. The winner of the contest would not only become the voice of the speaking clock, but also be given a prize of 10 guineas or about £700 today, a somewhat paltry sum given the billions (after adjusting for inflation) the service has earned in the ensuing decades since its genesis.

The woman chosen for the gig was one Ethel Jane Cain, a telephonist. After being selected, Cain was given a script of things to say. She described the recording process in a 1957 Manchester Radio interview:

The way I recorded it was in jerks as it were. I said: “At the Third Stroke” (that does for all the times), and then I counted from One, Two, Three, Four, for the hours, we even went as far as twenty-four, in case the twenty-four-hour clock should need to be used, and then I said “…and ten seconds, and twenty seconds, and thirty, forty, fifty seconds”, and “o’clock” and “precisely”. The famous “precisely”. So what you hear is “At the Third Stroke it will be one, twenty-one and forty seconds”

She went on to note that “the real work was done by the engineers of the Post Office” who had to painstakingly fit all her lines together so they maintained a natural sounding cadence.

For those who’ve never called before, since 1936, the line spoken by the talking clock prior to announcing the time has remained more or less exactly as Ethel described it- the disembodied voice on the other end of the line simply states, with little variation: “At the third stroke, the time will be [insert time here]” At which point three beeps will play, the third of which will coincide with the exact time mentioned followed by a brief pause before the message plays again.

To call the service, users simply had to call 846, which spelled out the first three letters of the word “time”, leading to the service colloquially being known as “Tim” in the areas of the country using this number (other areas used other numbers until 1990 when the number you needed to dial was changed more simply to 123). To maintain the service, people calling were initially charged a single penny, a figure that has steadily risen over the years to 30p today, making the service incredibly profitable.

Officially introduced on July 24, 1936, the British speaking clock service received approximately 13 million calls during its first year of operation, a figure that becomes doubly impressive when you realise the service was only available in London for the first six years it existed.

With the massive number of calls coming in at all hours, to make sure people didn’t clog up the lines at any given time, the Post Office issued a briefing after the system was debuted, noting:

In view of the possibility of certain members of the public becoming so enamoured of the golden voice that they are impelled to listen to it for an indefinite period, an automatic device disconnects the circuit at the end of ninety seconds.

While the idea of people becoming “enamoured” with a recording of someone reading the time might seem silly, Brian Cobby, the third “golden voice” of the speaking clock claimed that he often received fan-mail, particularly from “older women”, who liked to call the speaking clock at night when they couldn’t sleep, just to listen to his soothing voice.

Speaking of Cobby, since its initial inception, there have been four “permanent” (non-guest) voices for the speaking clock, the aforementioned Ethel Jane (you can hear her time reading here), who provided the voice between 1936 and 1963; Pat Simmons (listen here), who provided it from 1963 to 1984; actor Brian Cobby (listen here), who lent his voice to the service from 1984 to 2007; and Sara Mendes da Costa (listen here, or if you live in the UK just call the number) who is the current voice of the service. All four of these individuals became the voice after entering a “golden voice” competition similar to the one previously discussed and were variously rewarded with cash prizes in addition to becoming the new voice of the service.

As for the accuracy of the speaking clock, though many maintain that the modern speaking clock is “accurate to within one five thousandth of a second”, this claim is disputed by the National Physics Laboratory who say that, owing to variable delays in the transmission actually getting to your phone: “you can probably expect the starts of the seconds pips to be accurate seconds markers within about one-tenth of a second.”

This said, the service does take an extraordinary amount of care in ensuring that the time they give is as accurate as possible, even attempting to account for the delay for the signal to reach your phone. The service is so accurate that a minor scandal was caused in 2013 when it emerged that employees at the Ministry of Defence had spent £40,000 of public money (about 130,000 calls) calling the service to synchronize their clocks over the previous three years, despite the fact that doing exactly that was explicitly banned by the Ministry of Defence in 2010.

This said, the service does take an extraordinary amount of care in ensuring that the time they give is as accurate as possible, even attempting to account for the delay for the signal to reach your phone. The service is so accurate that a minor scandal was caused in 2013 when it emerged that employees at the Ministry of Defence had spent £40,000 of public money (about 130,000 calls) calling the service to synchronize their clocks over the previous three years, despite the fact that doing exactly that was explicitly banned by the Ministry of Defence in 2010.

Other than MOD employee calling to synchronise watches, it has been noted that the service fields the most calls on four very specific days: The day the clocks go forward and back for daylight saving time, New Year’s Eve (with people trying to ensure they celebrate the new year at the exact right moment) and November the 11th (so that they can observe the traditional 2 minutes silence for Remembrance Day at the exact right time, 11AM).

Despite the huge technological leaps made in the last few decades that would seem to make such a service obsolete, the speaking clock service still fields an estimated 30 million calls every year or about 82,000 calls per day. That said, this is markedly less than a little under a decade ago before the ubiquity of smart phones, when the service was pulling in an average of about 200,000 calls per day. With either numbers, at 30p a call, the speaking clock is still raking in the money.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Time Before Ubiquitous Clocks

- Why Clocks Run Clockwise

- The Surprisingly Interesting Story Behind Why Grandfather Clocks are Called That

- Why We Say “O’Clock”

- The Real Name of the Clock Tower Incorrectly Called “Big Ben”

Bonus Facts:

- At certain times of year the profits from calls to the speaking clock are donated to various charitable causes and the service has infrequently employed the use of guest voices to encourage more calls during these periods. Notable guest voices include the voice of Tinkerbell, Mae Whitman, in 2008 and a 12 year old girl called Alicia Roland in 2003 to promote the children’s charity, Childline.

- In America, people calling the operator to ask for the time grew to be such a problem for the New England Telephone and Telegraph Company, that in 1918 they issued an official statement saying that their operators would no longer tell people the time, citing that doing so was “interfering with the efficiency of the service”. How many calls were they getting? Despite the telephone not exactly being something everyone had at this point in history, they were receiving over 100,000 such calls per day in New England alone.

- During the Cold War in the UK, the plan in the event of a nuclear attack was to utilise the speaking clock service to trigger the automatic warning sirens, as well as inform any callers of the attack. The reasoning for using this system was that the service was called so often that a failure in the system would be reported immediately without anyone officially needing to monitor it. So it made more sense to use it rather than create a new dedicated system that might fail without anyone noticing for a while.

- One slight change to this general script for the UK speaking clock occurred between 1986 and 2008, when the service was sponsored by the watchmaker, Accurist, with the new line being “At the third stroke the time, sponsored by Accurist, will be [insert time here]”. Given that during these near two and a half decades the speaking clock was called a few billion times, this is likely one of the most listened to sponsored message in the history of advertising.

- Ethel Cain starred in a movie in 1935 called, Vanity, her only known screen credit. The movie is considered lost and no known copies of it are known to exist.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|