The Curious Tail errr, Tale of F.D.C. Willard

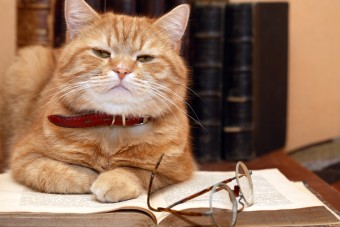

In the world of physics the name F.D.C. Willard is simultaneously treated with both reverence and derision. On one hand, he co-authored an often cited paper on low temperature physics at age 7 and was the sole author of another entire paper on the subject in French just a few years later at age 12. On the other hand, he was also a cat.

The story of Willard’s foray into the world of low temperature physics began in 1975 when his eventual co-author, Professor Jack H. Hetherington, asked a colleague at Michigan State University to read over a paper he’d written, Two-, Three-, and Four-Atom Exchange Effects in bcc 3He.

After reading over the paper, Hetherington’s colleague came back with some unfortunate news- while the content of the paper itself was sound, Hetherington had made a rather silly mistake. You see, throughout the paper, he had often referred to himself using the words “we” and “our”. Normally this wouldn’t have been a big deal; however, the journal Hetherington was submitting the paper to, Physical Review Letters, had a general rule in place that stated papers with a singular author shouldn’t use the first person plural.

Being the 1970s, Hetherington had typed up the entire paper using a typewriter, so fixing this mistake would have taken him more time than he was willing to invest in it. Being someone with a PhD in physics, Hetherington was no dummy and came up with an easy solution- he decided to make his pet Siamese cat, Chester, a co-author.

Wanting to give his furry friend a little more credibility, Hetherington stylised Chester’s name as “Felis Domesticus Chester, sired by Willard” which was shortened to “F.D.C. Willard”.

Hetherington’s ruse worked and a few months later on the 24th of November in the 35th edition of Physical Review Letters, they published “Two-, Three-, and Four-Atom Exchange Effects in bcc 3He” co-authored by one J. H. Hetherington and his colleague, F. D. C. Willard.

The fact that the mysterious F.D.C. Willard was actually just a cat was first revealed publicly when, according to Hetherington, “a visitor to [the university] asked to talk to me, and since I was unavailable asked to talk with Willard. Everyone laughed and soon the cat was out of the bag.”

It was made more widely known when Hetherington was sent several copies of the paper to sign and he decided to double down on his ploy by daubing Chester’s paw in ink and slapping it on the page. One of these copies ended up being sent to physicists in Grenoble who were planning on inviting Professor Willard to the “15th International Conference on Low Temperature Physics” in 1978. However, upon seeing the inky paw print on the page and realising that Willard must be a cat, the group making up the list of who to invite decided that neither Willard nor Hetherington should be included on their roster that year.

Even more controversy followed when it emerged that Hetherington’s wife was sharing a bed not only with her husband, but F.D.C. Willard as well, sometimes at the same time…

Despite the public relations problem, F.D.C. Willard continued his work in academia, helping out his colleagues by being present in numerous debates about low energy physics with his input being described as “helpful” by his co-workers in private and official correspondence.

Willard’s contributions to science didn’t go overlooked by his peers in other areas either. For example, in Organic Chemistry: The Name Game, Willard was mentioned; they stated: “Although [his] future in physics is uncertain, we like his style and hope he gets tenure.”

And, in fact, on November 26, 1975, the chairmen of the physics department at Michigan State University, Dr. Truman O. Woodruff, wrote a letter to Hetherington stating,

I should never have had the temerity to think of approaching so distinguished a physicist as F.D. C. Willard, F.R.S.C., with a view to interesting him in joining a university department like ours, which after all, was not even rated among the best 30 in the 1969 Roose-Anderson study. Surely Willard can aspire to a connection with a more distinguished department.

However, heartened by your view that he might conceivably deign to look with favor on the modest opportunity that we have to offer, I do beseech you– his friend and even collaborator– at the most propitious possible time (say, some evening when the brandy and cigars are going around) to raise the question with him (with all possible delicacy, I need hardly add). Can you imagine the universal jubilation if in fact Willard could be persuaded to join us, even if only as a Visiting Distinguished Professor?

Given there are no records of F.D.C. Willard on the university’s payroll, we can only assume he turned up his nose and walked away from such a delectable opportunity, as cats are wont to do. That said, Hetherington did refer to Willard as the university’s “Rodentia Predation Consultant”. On top of this, Willard was often cited as being instrumental to a number of “departmental experiments related to angular momentum and gravitational forces” by Hetherington’s peers in Michigan.

This wasn’t the end of his academic career, though. In 1980, Willard dusted off his pen and effortlessly authored the paper, “L’hélium 3 solid. Un antiferromagnétique Nucléaire” entirely in French for the magazine, “La Recherche”.

In reality, the paper had been written by a collective of researchers from France and America, including Hetherington, who couldn’t agree on certain elements of its content. When no satisfactory compromise could be reached between the members of the group, Hetherington suggested they make F.D.C. Willard the sole author so that if anyone found fault with it, none of their names would be sullied.

Sadly, F.D.C. Willard passed away in 1982 at approximately 14 years old, but his legacy lived on in the world of science thanks to the fact that the paper he co-authored actually ended up being fairly influential and often cited for its scientific merits.

When later asked why he made his cat a co-author on the paper, beyond the aforementioned need of not wanting to take the time to fix the instances of the royal “we”, Hetherington explained that “most of us are paid partly by how many papers we publish, and there is some dilution of the effect of the paper on one’s reputation when it is shared by another author. On the other hand, I did not ignore completely the publicity value, either. If [the paper] eventually proved to be correct, people would remember [it] more if the anomalous authorship were known. In any case, I went ahead and did it and have generally not been sorry. Most people are amused by the concept, only editors, for some reason, seem to find little humour in the story.”

In the end, to honor F.D.C. Willard’s role in helping to break down the barriers keeping felines out of human science careers, the American Physical Society announced on April 1, 2014 that all papers authored by cats would be made “freely available” for the public to read henceforth. They also added that “Not since Schrödinger has there been an opportunity like this for cats in physics.”

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Why are Calico Cats Almost Always Female?

- Why and How a Cat Purrs

- Why Cats Like Catnip

- Domestic Cats Can Fall From Any Height With a Remarkable Survival Rate

- Working for Figurative Peanuts and Literal Beer, the Fascinating Story of Jack the Signal”man”

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Immunogist Polly Matzinger did a similar thing in the late 70s, putting her dog Galadriel Mirkwood on a paper in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. Apparently the editor of JEM was so upset, he banned her from publishing in that journal for years afterwards.

Matzinger is a legend. She worked in a Playboy Club and was “discovered” by some scientists who suggested she go to graduate school. She did and has been a top notch scientist ever since.