How Did They Get the CGI in the 1993 Jurassic Park to Look So Good?

Regardless of your feelings about the overall quality of the film itself, you have to admit that for a movie released in 1993, Jurassic Park contains some mighty fine lookin’ dinosaurs. In fact, the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park look so good that many film critics and fans contend that the film’s CGI effects still hold up today nearly three decades later, with some even going so far as to say they look better than some scenes in more recent Jurassic Park films. The funny thing about that, however, is that while Jurassic Park is often singled out for its groundbreaking CGI, there are actually very few moments in the film that were realised using such newfangled technology.

Regardless of your feelings about the overall quality of the film itself, you have to admit that for a movie released in 1993, Jurassic Park contains some mighty fine lookin’ dinosaurs. In fact, the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park look so good that many film critics and fans contend that the film’s CGI effects still hold up today nearly three decades later, with some even going so far as to say they look better than some scenes in more recent Jurassic Park films. The funny thing about that, however, is that while Jurassic Park is often singled out for its groundbreaking CGI, there are actually very few moments in the film that were realised using such newfangled technology.

You see, despite being some 127 minutes long, Jurassic Park contains a mere 14 minutes of on-camera dinosaur action, with a huge number of scenes seeming to contain dinosaurs in the action actually having the dinosaurs doing their thing off camera, with specific quick cuts, sound effects, and actor and scene elements like plant-life, cups of water, etc. reactions making the dinosaurs’ presence known and felt in the scenes even though you don’t actually see them.

And as for those 14 minutes the dinos do appear on camera, only 5-6 minutes were realised using CGI. The rest were achieved via everything from a full size, just under 5 ton, extremely realistic looking and moving T-Rex, to dudes running around in very realistic looking velociraptor costumes.

Or to put it another way- the film that is considered the gold standard for awesome CGI achieved this acclaim via doing everything possible NOT to use CGI and, in the few minutes it did use it, doing an awful lot to encourage viewers to not pay too close of attention to the CGI elements, as you’ll soon see when we get into specific examples.

You see, Spielberg initially wanted no CGI whatsoever for the film. His plan for the dinosaur effects in Jurassic Park was to accomplish it all via a combination of stop motion and animatronics, with the former to be handled by stop motion wizard Phil Tippett (then an Oscar winner for his work in Return of the Jedi) and the latter to be handled by special effects guru Stan Winston (then a recent recipient of a couple Academy Awards for his work in Terminator 2, as well as previously winning one for his work in Aliens). The idea being that Winston and his team would create animatronic dinosaurs and appropriate costumes and the like to be used for close ups, while Tippet and his team would handle the long shots where motion that couldn’t be easily achieved by other methods was needed.

Spielberg was reportedly highly resistant to the idea of using any CGI primarily because he believed how fake it would look given the technology of the day would more or less ruin the film. Remember, this was an era when Windows 3.1 was the bees knees, to put the state of things in perspective. However, the wizards at George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic were rather ahead of their time in a lot of ways and decided not to take “no” for an answer, creating a demo of what they could do to convince Spielberg.

In order to ensure they’d convince him with this demo, they set about creating the hardest shot they could think of- a T-Rex walking directly towards the camera in broad daylight with nothing hidden. This footage was then screened to Spielberg and members of the effects crew, including both Winston and Tippett.

According to those present that day, the reaction from everyone was one of complete shock, with Tippett perhaps most affected of all as he was essentially witnessing the obsolescence of a huge amount of his expertise. As he would later state, “The change was devastating. I had different concessions… and all of a sudden, the plug was pulled…”

At the time, he simply turned to Spielberg and stated, “I think I’m extinct.” This was the direct inspiration for the line in the film in which Dr. Grant says, “I think we’re out of a job.” And Malcolm then says, “Don’t you mean extinct?”

At this point Spielberg was partially onboard. However, critically, and a lesson lost on many a director then until now, was that Spielberg still only wanted to use this technology when there was no other way to achieve the scene better with either practical effects or, in many cases, simply having the thing that would otherwise need CGI’d seeming to be in the scene, but not actually show up on camera at all.

For example, consider perhaps the most famous sequence in the entire film- the nighttime T-Rex attack on the Jeeps. In this, the majority of the time the T-Rex’s presence is more or less felt off camera, with this all augmented by generally quick cuts between the very real life-size version of the T-Rex and, when needed, a CGI version of the same. With regards to the former, beyond being created to move in extremely realistic ways, the life-size version that appeared on camera was also extremely helpful to the digital animators as it not only gave them a model to mimic, but also helped them do things like achieve perfectly consistent lighting in the scene and the like.

On top of that, during that scene, there’s a shot where the T-Rex is distracted by a torch and a CGI version of itself walks away from the camera, something the real thing couldn’t do. If you watch the moment in question back, you’ll notice that every step the T-Rex takes shakes the camera and vehicle the characters are sitting inside of. It’s a minor detail sure, but it’s one that not only briefly blurs the visuals a little as the dinosaur is moving, somewhat masking the CGI’s weaknesses, but also sells you on the idea that the thing you’re seeing is actually there- all using a subtle and very easy to achieve practical effect.

On that note, effects supervisor Dennis Muren (who won an Oscar for his work on the film) would later note in an interview with The Hollywood Reporter that a key aspect of what made the CGI dinosaurs in Jurassic Park seem so real is that he and his team gave them a sense of “weight and gravity.”

For an example of a scene where proper weight and gravity isn’t given to a CGI character, go watch this scene from the 2014 Transformers: Age of Extinction and notice how not a single thing on screen other than the humans moves in response to a 30 ton robot backflipping into frame and firing a giant machine gun into the air. Even the shipping container the giant robot lands on doesn’t show any signs of having said massive being curb stomping it, other than a few fake looking CGI sparks.

While you may not consciously register this, the subtle effect is that, while in many ways the CGI on this film is light-years ahead of the original Jurassic Park, because of poor direction and production, it seems much less real looking when nothing in frame is physically reacting to the otherwise very realistic looking CGI object.

In contrast to the Michael Bay directed Transformers, in Jurassic Park, beyond things like the aforementioned camera shake, we have other samples like when a CGI version of the T-Rex steps on the Jeep, it squishes it into the mud and crushes the physical object appropriately. This not only makes it seem more like a real dinosaur is in the scene, but simultaneously draws your eyes to the people being crushed underneath to see what’s happening to them, and away from paying attention to the CGI dinosaur- thus both getting around some of the limitations of CGI at the time and adding an awful lot of tension to the scene to boot- a master director just showing off basically.

And then in other scenes, instead of using a CGI dinosaur which many a modern director would default to, instead they cut to a shot of a physical 30 foot tall animatronic dinosaur headbutting its way into a Jeep full of screaming actors who are all reacting to the same, very real, thing at once. If you read up on many an interview with Stan Winston on this, he maintains that the beauty of practical effects instead of CGI is that the reaction they inspire from actors is more real, which audiences do pick up on, even if not fully consciously registering the subtle difference.

On the flipside, Winston also is quick to point out the limitations of his craft. For example, a weakness of animatronic models and practical effects is that they’re often unwieldy and in specific regards to the animatronic and model dinosaurs featured in Jurassic Park, not all that nimble at times. Although if you go watch footage of the movements of the near 5 ton T-Rex his team made, it seems rather shockingly nimble in our opinion and its realistic movements are incredible.

Whatever your opinion there, another trick used in that rather famous T-Rex attacking the Jeep sequence is to both set it at night and in the rain to help obscure the limitations of both the practical and digital effects. A similar example is that of the kitchen scene which shows a bunch of velociraptors trying to nibble on the Unix user and her brother. First, the scene is intentionally dark with lots of shadows and quick cut scenes showing only bits of the dinosaurs. From there, believe it or not, much of the scene was shot not using CGI, but using some guys in very realistic looking velociraptor costumes. CGI was only used for a few select moments that were too difficult for the stunt guys, such as jumping into the air onto the counter. This is one of the least realistic looking scenes of the film when you watch really closely, but in the moment with the way things are cut and shot and the elements that draw your eye, it comes off looking extremely realistic. You just don’t notice the dinosaur doesn’t look nearly as good as the split second before or after when they were using dudes in costumes.

This ensures the audience is never completely taken out of the scene, unlike, say, the 2001 The Mummy Returns where the Scorpion King looks laughably fake during the final fight, almost completely ruining the climax of the film- a particularly odd choice given that the Rock is already capable of being a rather terrifying hulk of a beast, without needing CGI to achieve the effect.

Or perhaps another great example of this is the difference between the massively better looking 1983 Return of the Jedi Jabba the Hutt vs Jabba’s cameo in the 1997 Special Edition of A New Hope. In the former, Jabba looks incredibly realistic because, well, it’s a real thing being shot in somewhat dim lighting in many scenes to boot. In the latter, he is featured completely CGI in broad daylight, with the effect being he looks incredibly fake to the point that it’s shocking that someone didn’t smack George Lucas on the nose with a rolled up newspaper and say “NO!”

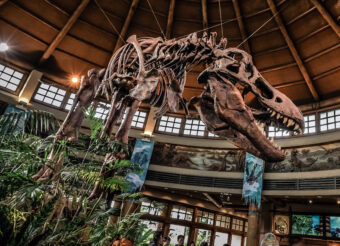

Going back to Jurassic Park, a contrasting example is the film’s final action sequence in which the T-Rex gets in a fight with the velociraptors. As you might expect, this scene is realised almost entirely with CGI and with much better lighting than many other CGI scenes in the film, which could potentially be a problem. However, a number of tricks were used to get around the issues. For example, to add that, to quote, “weight”, subtle things occur to help make the dinosaurs seem more real. For instance, at one point instead of having a raptor jump from up high down to the ground directly, the CGI raptor is instead made to jump onto the skeleton of a T-rex, with the very real prop shaking and breaking appropriately in response.

Similarly, rather than having the CGI dinosaurs going at it with little interaction with their environment, at one point the T-Rex throws a raptor into the physical skeleton, with, again, the physical object made to react just like it would if that had really happened- once again, subtly making the scene feel more real looking than if the T-Rex had just thrown the raptor across the room without hitting anything but the unyielding floor.

If you really pay attention to that scene, there are numerous subtle queues like this used with the CGI dinosaurs constantly affecting actual real, physical objects. This is all combined with extremely quick cuts and pans away from the CGI dinosaurs, as well as occasional objects coming in between you and being able to see said dinosaurs.

The net effect being to make them seem like they are in frame a lot longer and more than they actually are. For example, at one point a CGI raptor is only in scene for about two seconds as it leaps towards the humans. In that extremely brief shot, when it lands, it accidentally kicks a bone on the floor and then stops moving at all for the rest of the scene. The instant it freezes, the camera very quickly pans away, following the actors running away, which, combined with the kicked physical object, all draws your eye away from the oddly mostly motionless CGI dinosaur.

Another factor that made the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park seem so realistic is that while Phil Tippett didn’t get to make any stop motion footage for the film as originally planned, he did serve as a supervisor. Why is this important? Well, digital effects artists working for Industrial Light & Magic would later note that Tippett’s literal decades of experience working with animal motions was an invaluable resource for helping make the dinosaurs seem to move in realistic ways. He was also key in ensuring uniformity of movement and behaviour between the team working on the animatronic dinosaurs and the one working on the CGI ones.

On that note, as a brief aside, Phil Tippett’s officially credited role in the production of Jurassic Park was that of “Dinosaur Supervisor”, with many a joke being made later about this- like “One job, Phil! You had one job!”, referencing the fact that despite his supervision, the dinosaurs in the film were constantly running amok.

Going back to the benefit of having the physical dinos, as alluded to, critically, unlike a film relying exclusively on CGI for various elements, the digital animators had those physical dinos on camera in several scenes to build off of in the scenes themselves. This helped the cuts back and forth between CGI dinosaurs and physical ones be extremely seamless, despite the limitations of the technology of the age.

Yet another subtle difference often suggested making the CGI in Jurassic Park look objectively better than some CGI seen in movies today is that the movie didn’t make use of unnatural color grading. This is extensively used, and many say massively overused, in some modern films. While it can be of benefit in certain sequences or films to achieve a specific effect or feeling to the scene, perhaps most famously and appropriately used in films like The Matrix and O Brother Where Art Thou, overly aggressive ubiquitous digital color grading can sometimes make a movie or scene look slightly unnatural, which in some cases makes the CGI it contains also seem more unnatural than it would have.

Thus it is argued that Jurassic Park, in contrast, has a bit more realistic feel precisely because the world they exist in looks just like our own in coloration- for example, no overlay of a slight blue tint, which is frequent in Jurassic World. As author David Bell notes on this, “This is why the effects in The Avengers and Dawn Of The Planet Of The Apes look so darn good in comparison. Along with dumping… tons of money into the CGI, those movies didn’t wash everything over with color grading to make it look like Middle-goddamn-earth. It’s the actual world, with actual earth tones.”

Whatever your opinion on that last point, to sum up- the reason the CGI looks so good in the original Jurassic Park is paradoxically because the film purposefully used CGI as little as possible, and in very specific ways to mask its limitations. And as for this masterful masking, beyond keeping the dinos off camera a shocking amount when you really pay attention, all while seeming to be in the scene when you’re just watching in the moment, it helped that those behind the film more or less made up a dream team of effects artists, all under the direct supervision of one of the most talented directors in Hollywood history. And, well, it showed.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Is It True That a T-Rex Couldn’t See You If You Didn’t Move?

- What Did People First Think When They Found Dinosaur Bones?

- How They Cobbled Together The Mighty Morphin’ Power Rangers From Footage of a Completely Different Japanese TV Show

- From Dream to 3-D Reality: The Fascinating Origin of Pixar

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

Jabba the Hutt isn’t a ‘he’. That’s a common misconception.

It’s my girlfriend.