That Time Two Comic Artist Independently Created Dennis the Menace on the Same Day an Ocean Apart

We’ve talked before about the bizarre Hollywood phenomenon of Twin Films – essentially films with near identical premises inexplicably released around the same time – and all of the machinations that can lead to them existing. Today, rather than focusing on an industry wide trend, we’re going to discuss a specific example of something similar- the bizarre tale of the time two comic artists based in the UK and US respectively somehow both created Dennis the Menace at almost the same time, with the first editions of each published on the exact same day, despite neither one knowing anything about what the other was doing.

We’ve talked before about the bizarre Hollywood phenomenon of Twin Films – essentially films with near identical premises inexplicably released around the same time – and all of the machinations that can lead to them existing. Today, rather than focusing on an industry wide trend, we’re going to discuss a specific example of something similar- the bizarre tale of the time two comic artists based in the UK and US respectively somehow both created Dennis the Menace at almost the same time, with the first editions of each published on the exact same day, despite neither one knowing anything about what the other was doing.

While it’s commonly misstated that the UK version of Dennis the Menace, which debuted in Beano #452, came out on March 17, 1951, in truth both Dennis the Menace comics hit the shelves on March 12, with the incorrect date for the British version coming from the fact that this date was on the original cover. As to why, a common practice at the time was to post-date editions to try to keep them on the shelves longer.

Beyond sharing a name, both characters own dogs that usually aid in their mischief, with American Dennis having a snowy white Airedale mix called Ruff, and British Dennis owning a “Abyssinian wire-haired tripehound” called Gnasher. Like their owners, each dog has a distinct personality, Gnasher being decidedly more violent than Ruff, with his favourite pastime being chasing and biting postman. Another similarity between the two Dennises is their penchant for causing mischief with a slingshot, which is considered to be a trademark of each character in their respective home markets.

That said, it should be noted for those unfamiliar that the British Dennis is an intentional menace who relishes in the mayhem he causes, whereas the U.S. version tends to be over all good natured and ends up being a menace in many cases via trying to do something good, but having it all go wrong.

Nevertheless, given the similarities, it should come as no surprise that soon after each comic hit the stands on the same day in 1951, news of each other’s comics quickly reached the two creators. While initially foul play was suspected, it became clear to all parties involved that the whole thing couldn’t possibly be anything but a massive, inexplicable coincidence.

In the end, both creators agreed to continue as if the other comic didn’t exist and the only real change made to either comic was that as both comics gained in popularity, the name of the British version evolved, initially just in foreign markets, but eventually everywhere to Dennis and Gnasher.

During discussions about how each creator came up with the idea of Dennis the Menace, it was revealed that British Dennis was the brainchild of Beano editor, George Moonie. Moonie was inspired to create the character after hearing the lyric “I’m Dennis the Menace from Venice” while visiting a music hall. With this lyric in mind, Moonie tasked artist David Law with creating a character called, you guessed it, Dennis the Menace, saying simply that the character was a mischievous British schoolboy.

Although Law was responsible for drawing Dennis from his conception until 1970 when Law fell ill, the now iconic look of Dennis was first suggested by Beano Chief Sub Ian Chisholm who is said to have sketched a rough drawing of what would come to be Dennis’ default look on the back of a cigarette packet while Chisholm and Law were at a pub in St Andrews, Scotland.

Billed as “The World’s Wildest Boy!” in his debut strip, proto British Dennis looked markedly different from his modern counterpart, with some of his more iconic features, such as his pet dog and bestest pal Gnasher or his iconic red and black striped sweater, not being introduced until later comics.

In the end, Dennis the Menace played a big part at revitalizing Beano, as noted by Beano artist Lew Stringer, “Dennis the Menace was like a thunderbolt. The Beano was flagging by 1950 and no longer radical. But there was an energy to Dennis the Menace, it was modern and became one of the first naughty kids characters of the post-war period.”

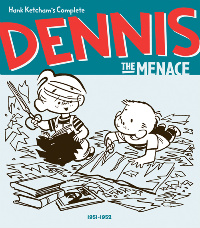

As for American Dennis the Menace, he was the creation of Hank Ketcham. Ketcham briefly attended the University of Washington in Seattle, but had a passion for drawing from a very young age when a family friend had showed him his, to quote Ketcham, “magic pencil”, and how it could draw things like cartoon characters such as Barney Google.

Fast-forward to his freshman year of college in 1938, after seeing “The Three Little Pigs” Ketcham promptly dropped out of school and left Seattle, stating,

I had one thing on my mind: Walt Disney. I hitchhiked to Hollywood and got a job in an ad agency, changing the water for the artists for $12 [about $219 today] a week. Which was OK because I lived at a rooming house on Magnolia–three meals a day and a bike to ride to work–for $6 a week.

Then I got a job with Walt Lantz at Universal, assisting the animators, for $18. It was the tail end of the glory days of Hollywood and I loved it! I was on the back of the lot, where W.C. Fields, Bela Lugosi, Crosby, Edgar Bergen were all parading around. My neck was on a swivel! Marvelous!

As he notes there, he eventually achieved his goal, doing some work for Disney on movies like Fantasia, Bambi, and Pinocchio.

When the U.S. entered WWII, he found himself in the Navy drawing military posters for things like War Bonds and the like. By 1950, he was working as a freelance cartoonist. On a fateful day in October of that year, his toddler son, Dennis, did something that changed the family’s fate forever.

His wife, Alice, went to check on the toddler who was supposed to be napping, but instead she found Dennis’ dresser drawers removed and contents unceremoniously dumped out, his curtain rods removed and dismantled, mattress overturned and just a general mess everywhere.

Ketcham would recount in an interview with the Associated Press on the 50th anniversary of his comic that Alice remarked in an exasperated tone after witnessing the destruction, “Your son is a menace!”

This statement resonated with Ketcham who quickly devised and refined the idea of a mischievous toddler who accidentally causes wanton destruction wherever he goes. Dennis the Menace was born, and a mere five months later debuted in 16 newspapers. This is despite the fact that Ketcham himself would later state, “Oh, the drawings were terrible! Even when I started with Dennis they were just wretched! How any editor ever bought that junk…”

Nevertheless, within a year of its debut, 245 newspapers across the world had picked it up representing a readership of over 30 million people. At its peak, the number of outlets that carried Dennis the Menace grew to over 1,000.

Unfortunately, things did not have a happy ending for the real Dennis. Much like with Christoper Robin Milne, who A.A. Milne based his character of Christopher Robin on, Dennis came to loathe the fact that his father had created a famous character after himself. Unlike Christoper Robin, Dennis never got over it.

That said, despite his son’s accusations, Ketcham vehemently denies ever using anything from his son’s childhood as fodder for the comic other than the name, noting he almost always used a team of writers to come up with the comics’ content, stating, “Anyone in the humor business isn’t thinking clearly if he doesn’t surround himself with idea people. Otherwise, you settle for…mediocrity – or you burn yourself out.”

Whatever the case, the comic was perhaps just a side issue. You see, as her husband’s fame grew, Dennis’ mother became an alcoholic and by 1959 she filed for divorce. Around the same time, with Alice no longer capable of taking care of Dennis, he was shipped off to a boarding school. Said, Dennis, “I didn’t know what was going on except that I felt Dad wanted me out of the way.”

Very soon after, his mother died after mixing barbiturates with a lot of alcohol. As for Dennis, Ketcham didn’t end up getting him from boarding school to attend the funeral, nor did he tell him about his mother’s death until weeks later, reportedly as he didn’t know how to break it to him, so delayed as long as possible. Said Dennis of this, “Mom had always been there when I needed her. I would have dealt with losing her a lot better had I been able to attend her funeral.”

Things didn’t improve when mere weeks later, Ketcham married a new woman, then moved the family off to Switzerland where he once again placed Dennis in a boarding school, which ultimately didn’t work out. To begin with, his new wife and Dennis weren’t exactly pals. Said Ketcham, “Jo Anne was unused to children. and she and Dennis didn’t get along.”

Seeing his son struggling academically because of a learning disability, combined with being in a foreign country and issues between his new wife and Dennis, Ketcham sent Dennis off to a different boarding school back in the United States where he hoped he’d be more comfortable.

After graduating two years later than most, Dennis joined the Marines for a tour in Vietnam and subsequently suffered from severe post-traumatic stress disorder.

As for his relationship with his father, it never improved, with Ketcham even losing track of him completely at one point. As Ketcham stated when asked about his son, “He’s living in the East somewhere doing his own thing. That’s just a chapter that was a short one that closed, which unfortunately happens in some families… He checks in about twice a year. And if he needs something, I try to help him.”

As you might imagine from all this, Ketcham would come to greatly regret using his son’s name for his character because of how he felt it negatively impacted him. “These things happen, but this was even worse because his name was used. He was brought in unwillingly and unknowingly, and it confused him.”

He also regretted not being there for his son. “Sometimes, young fathers scrambling to make a living, to climb the ladder, leave it to the mother to do all the parental things. But you get back what you put into a child. It’s like a piano. If you don’t give it much attention, you won’t get much out of it… I’m sure Dennis was lonely. Being an only child is tough.”

He goes on, “In my family now. I’m much more active with the kids and their schooling than I was before. I listen better. And I think I’m more patient. Maybe not. But I’d like to think so.”

As for Dennis’ side, he stated, rather than a successful, famous father, “I would rather have had a father who took me fishing and camping, who was there for me when I needed him… Dad can be like a stranger. Sometimes I think that if he died tomorrow, I wouldn’t feel anything.”

When Ketcham died on June 1, 2001, Dennis didn’t show up for the funeral and a family spokesman stated they hadn’t heard from him in years and didn’t know where he was.

To finish on a much lighter note, in 1959, Ketcham was invited to visit the Soviet Union as a part of a cartoon exchange trip. Never ones to miss an opportunity, the CIA asked Ketcham if he wouldn’t mind sketching anything significant he saw while in the Soviet Union. Said Ketcham, “We were flying from Moscow to Kiev, and it was during the day and I looked out the window and I saw some shapes. I had my sketch book, and I would put them down, and the flight attendant would walk by, and I would put a big nose and some eyes and make the whole thing into a funny face. So I had a whole book of funny-face cartoons at the end that I didn’t know how to read.” Needless to say, the CIA didn’t exactly appreciate his work.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- When a Marketer Invents a Comic- The Story of Garfield

- How Peanuts Became the Defining Comic Strip of Our Time

- What Ever Happened to the Creator of Calvin and Hobbes?

- On The Far Side

Bonus Facts:

- Going back to British Dennis, Kurt Cobain was known to wear a jumper remarkably similar to that of the British Dennis the Menace on stage. As it turns out, the jumper was a genuine piece of official Dennis the Menace merchandise, though the singer didn’t know this. Apparently Courtney Love bought the jumper for Kurt for for £35 (about £70 or $90 today) from a fan called Chris Black at a concert in Northern Ireland in 1992 after taking a liking to it.

- Speaking of having to find a way to be original week after week in comics, Charles Schulz, creator of Peanuts, once sagely stated, “A cartoonist is someone who has to draw the same thing every day without repeating himself.” That’s a tall order for someone who created nearly 18,000 strips- and it wasn’t always easy. On this note, Cathy Guisewite, creator of the comic strip Cathy, revealed in an interview that Schulz once called her in something of a panic as he couldn’t think of anything to draw and was doubting whether he’d be able to come up with anything. Exasperated, she stated, “I said, ‘What are you talking about, you’re Charles Schulz!’… What he did for me that day he did for millions of people in zillions of ways. He gave everyone in the world characters who knew exactly how we felt.”

- Bill Watterson, creator of Calvin and Hobbes, famously not only passed up but fought vehemently against merchandising of Calvin and Hobbes, costing himself many tens of millions of dollars in revenue. He stated of this that it wasn’t so much that he was against the idea of merchandising in general, just that “each product I considered seemed to violate the spirit of the strip, contradict its message, and take me away from the work I loved.” Despite this, it’s not terribly difficult to find merchandise of Calvin and Hobbes, but all are unauthorized copyright infringements, including the extremely common “Calvin Peeing” car stickers. Despite never having earned a dime from these, Watterson quipped in an interview with mental_floss, “I figure that, long after the strip is forgotten, those decals are my ticket to immortality.”

- Most of the characters and names in Winnie the Pooh were based on creator A.A. Milne’s son’s toys and stuffed animals with the exception of Owl, Rabbit, and Gopher. Christopher Robin Milne’s toy teddy bear was named Winnie after a Canadian black bear he saw at the Zoo in London. The real life black bear was in turn named after the hometown of the person who captured the bear, Lieutenant Harry Colebourn, who was from Winnipeg, Manitoba. The bear ended up in the London Zoo after Colebourn was sent to England and then to France during WWI. When he was sent to France, he was unable to bring the bear so gave it to the London Zoo temporarily and later decided to make it a permanent donation after the bear became one of the Zoo’s top draws. The “Pooh” part of the name was supposedly after a black swan that Christopher Robin Milne saw while on holiday. A black swan named Pooh also appears in the Winnie-the-Pooh series.

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

This site needs some editors and copy editors. Great subjects but tough going at times.