Discovering the Caves of Xanadu

One Saturday in 1974, two young men affiliated with Southern Arizona Grotto, a spelunking, or “caving,” group based in Tuscon, Arizona, were out exploring, looking for new caves near the Whetsone Mountains. Randy Tufts and Gary Tenen traveled about an hour outside of Tucson, where they were roommates at the University of Arizona. As they often did, Tufts and Tenen carried only the minimum amount of caving equipment they needed: two miners’ hard hats with gas carbine lanterns affixed to the top, some rope, hammers and chisels, and snacks.

Tufts had been introduced to spelunking by an uncle, and on this day he wanted to explore an area he’d first seen seven years earlier, when he was still in high school. He recalled a large sinkhole with a narrow crack descending into bedrock. On a recent walk, he’d rediscovered the sinkhole and also noticed that the U-shaped hill next to the sinkhole had what appeared to be a collapsed cave entrance. He wondered whether there was something interesting under the hill.

THE DISCOVERY

Tufts and Tenen found the spot and lowered themselves into the 15-foot-deep sinkhole, a dry and dusty space with a skull and crossbones carved in one wall. They found footprints, a couple of broken stalactites (mineral formations, or “dripstones,” that hang like icicles from the ceiling of a cave), and a 10-inch-wide crack. But most important, they noticed a breeze moving through the crack—a moist, warm breeze that carried the smell of bats, a sure sign of an interesting cave.

At 5’7″, Tenen was the smaller of the two, so he pushed his body through the crack first. Tufts was nearly six feet tall and 170 pounds, and had to exhale deeply and practically turn a somersault to push his body through. But another five feet down, they entered a living room-sized chamber with a stalagmite (a cone-shaped dripstone that rises from the floor of a cave) in the center. They knew there had to be more, so they continued until they found a 10-inch-high passageway, the source of the air current. They followed it, crawling on their bellies through 20 feet of gravel until it ended in a rock barrier with a single hole the size of a grapefruit—which cavers refer to as a “blowhole.”

SODA STRAWS

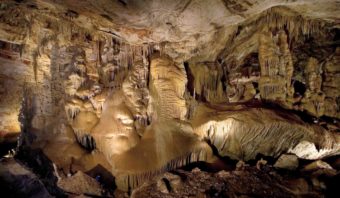

For hours, the two men chiseled at the blowhole until both were able to squeeze through. They found a corridor with damp stalactites hanging from the ceiling, as well as delicate “soda straws,” tubular mineral formations that grow about a tenth of an inch every century and can eventually form into stalagmites. It was dank and humid, and there were no signs that any humans had ever been in this part of the cave.

But that was just the beginning. As they moved through the cave, they found a series of “rooms” filled with wondrous formations. Orange stalactites hung overhead, soda straws dripped, calcite scrolls unrolled before them, and piles of bat guano towered (and stunk). Some of the rooms were so vast that Tenen and Tufts’s lamps, which threw light for only about 50 feet, couldn’t illuminate them. They wanted to explore and see how far the cave went, but they were experienced spelunkers and knew better than to go too far without additional light sources and without anyone else knowing where they were. Stunned by their discovery, they returned the way they’d come and decided to come back the following week.

IT’S ALIVE!

The two men had just discovered a cave on par with the finest caves in the world. And unlike some other popular caves, this one was still alive. By comparison, the world-famous Carlsbad Caverns is mostly dry. Another famous cave, Colossal Cave, is dry and dusty. But the wet, dripping quality of this newly discovered cave meant that the 40,000- to nearly 200,000-year-old flowstone, stalactites, and stalagmites were still growing.

Later visits unearthed more astonishing discoveries. One soda straw was an unheard-of 20 feet long. Another formation towered nearly 60 feet as a stalagmite grew up from the floor and eventually met a stalactite, all intricately rippled and lined in cascading drips and bulges. The two men named this massive formation Kubla Khan, after the poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and dubbed the cave Xanadu, after the capital of Khan’s empire, another reference to the poem (purportedly written following an opium-fueled dream).

TOP SECRET

Tufts and Tenen were worried about what would happen if this cave was widely discovered…and they had good reason. As cavers, they were careful never to touch formations, but looting, carelessness, and even garbage dumping at caves were rampant. And Xanadu wasn’t even remote—it was located just a half mile from a major highway. With fears for the protection of the cave on their minds, the two men decided to keep it a secret, even from their spelunking group. When they drove to visit the site, they covered up their spelunking equipment and carefully sealed up the entrance when they left. But they also knew that simply keeping the cave a secret might not be enough to protect it. If they had found it, why couldn’t others?

THE OWNERS

As the two young cavers looked for ways to protect the cave, they found that Xanadu wasn’t on public land; it was owned by a man named James A. Kartchner. Tenen and Tufts did extensive research on Kartchner, and every indication suggested he was a civically minded man, a leader in the local Mormon community. His wife, Lois, was a retired teacher, and six of the couple’s 12 grown children were doctors. In February 1978, Tenen and Tufts called Kartchner and told him, “We found something on your land we think you should know about.”

When they met Kartchner and his wife, they brought along slides with photos of the formations in Xanadu as well as images of Peppersauce Cave, a once-stunning Arizona cave that was now stripped of its formations and littered with trash and graffiti. Tufts and Tenen presented their plan to the Kartchners: they thought the best way to preserve the cave was not to seal it off but rather to commercialize it, to turn it into a tour cave and use profits to fund cave research and preservation.

By that April, Tufts and Tenen had brought Kartchner, as well as five of his sons, belowground. (One of the sons nearly got stuck in the blowhole.) Once they began to explore the wonders of the cave, they understood the majesty of what was below. To the Kartchners, the cave was a representation of the divine. The Kartchner family agreed to a partnership with Tufts and Tenen.

SIGN HERE

Tufts, Tenen, and the Kartchners all believed secrecy would be key to protecting the cave while they tried to figure out how to develop it. They took the secret so seriously that when Gary Tenen met his future wife in 1977, he made her sign a contract on their second date, promising to keep all information about Xanadu secret. The Kartchners also kept the cave secret from younger members of the family. (The 12 Kartchner children had 70 children and 19 grandchildren.) It was a rite of passage in the family to be taken into the cave. The first secret trip to the cave tended to take place as the children were beginning high school. The family’s photos of the cave were kept hidden, separate from other family photos. Mrs. Kartchner had a large framed color photo of Kubla Khan, but she kept it in her bedroom, away from public view.

Years passed as Tufts and Tenen researched ways to commercialize the cave. Tenen took jobs at commercial caves under an assumed name in order to learn more about how they might operate the cave. They hired a cartographer to chart Xanadu; they wrote letters to cave owners looking for information about how to run the financial side of the operation. But no matter how they looked at it, it was clear that there would be considerable expense involved in making the caves open to the public while also protecting them.

By 1980 the Kartchners’ enthusiasm for the venture began to wane. The economy was sputtering and gas prices were soaring. But perhaps most important, Mr. Kartchner met Howard Ruff, a financial adviser and the best-selling author of the book How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years. Kartchner asked about the advisability of spending the $300,000 they estimated would be needed to develop the cave for profit.

Ruff told him to forget it.

GOING PUBLIC

Once the Kartchners decided against investing their own money in the project, it seemed that the best route would be turning the cave into a state park. There were serious concerns about how the process would work. In order for the state or federal government to acquire it, there would have to be a public process, which would mean unveiling the secret cave. But it seemed they had no other choice.

In January 1985, Tufts and Tenen met with Arizona State Parks official Charles Eatherly without telling him what they were going to see, and even got the man’s permission to blindfold him so he wouldn’t be able to find his way back later. That was the beginning of a long and complicated political process, spanning the terms of multiple Arizona governors. In order to keep the cave secret, its purchase was slipped into a legislative bill without most of the legislators who were voting on the bill being aware of what they were voting on. On April 4, 1988, the Arizona state senate impeached Arizona governor Evan Mecham. The turmoil of the impeachment seemed a perfect time to sneak a bill through the legislature, granting appropriations for purchasing “the property known as the J.A.K. property”—that is, the property of James A. Kartchner.

The bill passed on April 27, 1988, and the secret finally got out: stories about the secret cave broke at several local TV stations and newspapers. One headline that day proclaimed: “Fairy Tale Cave to Become Arizona’s 25th State Park.” Only after the bill had passed was Tenen finally able to tell his children about the cave he’d been working to defend for more than a decade.

TODAY

Studying, mapping, and opening the cave to the public was a major undertaking for the state of Arizona. It took 11 years and cost $28 million. On Friday, November 5, 1999—25 years after Tufts and Tenen first entered Xanadu—two rooms of Kartchner Caverns State Park opened for public view for the first time.

Today, visitors to Kartchner Caverns can go on tours of many of the rooms of the cave, including the Throne Room (which contains one of the world’s longest soda straws), the Strawberry Room, and the Big Room, which is closed each year from mid-April through mid-October to accommodate nursery roosting for cave bats.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Canoramic Bathroom Reader. Weighing in at a whopping 544 pages, Uncle John’s CANORAMIC Bathroom Reader presents a wide-angle view of the world around us. It’s overflowing with everything that BRI fans have come to expect from this bestselling trivia series: fascinating history, silly science, and obscure origins, plus fads, blunders, wordplay, quotes, and a few surprises.

This article is reprinted with permission from Uncle John’s Canoramic Bathroom Reader. Weighing in at a whopping 544 pages, Uncle John’s CANORAMIC Bathroom Reader presents a wide-angle view of the world around us. It’s overflowing with everything that BRI fans have come to expect from this bestselling trivia series: fascinating history, silly science, and obscure origins, plus fads, blunders, wordplay, quotes, and a few surprises.

Since 1987, the Bathroom Readers’ Institute has led the movement to stand up for those who sit down and read in the bathroom (and everywhere else for that matter). With more than 15 million books in print, the Uncle John’s Bathroom Reader series is the longest-running, most popular series of its kind in the world.

If you like Today I Found Out, I guarantee you’ll love the Bathroom Reader Institute’s books, so check them out!

| Share the Knowledge! |

|