The Heroic Death of Chariots of Fire’s Eric Liddell

Imagine you dedicated your adult life to helping those less fortunate than yourself -that you spent your entire adult life trying to make the world a better place, and when you died (after sacrificing your own life for someone else’s) all most people remembered about you was that you once ran really fast… You’d be pretty annoyed right? Well that’s what happened to Eric Liddell. Although, as you’ll see, he probably wouldn’t have minded.

Imagine you dedicated your adult life to helping those less fortunate than yourself -that you spent your entire adult life trying to make the world a better place, and when you died (after sacrificing your own life for someone else’s) all most people remembered about you was that you once ran really fast… You’d be pretty annoyed right? Well that’s what happened to Eric Liddell. Although, as you’ll see, he probably wouldn’t have minded.

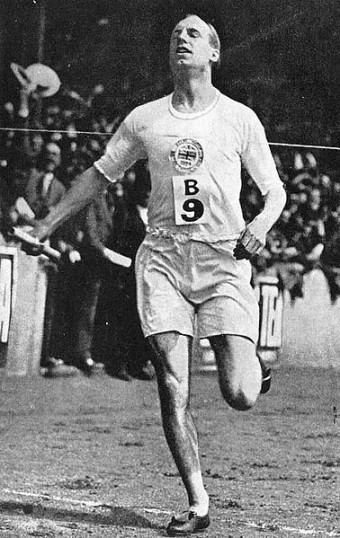

Liddell is mostly famous for being one of the subjects of the film Chariots of Fire, along with running buddy, Harold Abrahams. If you’re unfamiliar with the film or just want to see us clumsily stumble our way through describing the plot, the film basically follows Liddell and Abrahams through their university years up to their respective individual gold medal wins at the 1924 Paris Olympics. The film is noted to be fairly true to actual events, give or take a few creative liberties.

For example, one of the films most iconic scenes and one of the reasons Liddell himself is so famous is when he refused to compete in the 100 metre heat because it took place on a Sunday. As a devout Christian, Liddell steadfastly refused to run any race taking place on the Sabbath. In the film, this decision is made on Liddell’s journey to Paris from Britain. However, in real life Liddell was well aware of when the race took place several months in advance and planned appropriately, mainly training instead for the 400 metre race.

Liddell was harassed for months about his decision and was even reportedly “grilled” by the British Olympic Committee, particularly because the 100 metre was his best event and his best time in the 400 metre (49.6 seconds) had little chance of winning anything in the Olympics. Despite this, he didn’t back down on the issue.

Long story short, when the 400 metre final rolled around, Liddell, defied the odds and won the event with a world record performance (47.6 seconds). A performance usually attributed to the fact that Liddell treated the race as a dead sprint, running all 400 metres as fast as he possibly could. To quote the man himself when asked about his plan for victory.

I run the first 200m as hard as I can. Then, for the second 200m, with God’s help, I run harder.

Now we don’t want to downplay how impressive this achievement was, but it’s child’s play compared to what Liddell did next. We didn’t mention it in the intro, but Liddell was originally born in China prior to being raised and educated in Scotland. In fact, due to this, he’s often regarded as one of China’s first Olympic champions on top of all the other stuff he did. A year after his Olympic victory in 1925, Liddell went back to China to serve as a missionary like his parents before him had done.

For a few years, Liddell served as both a science and sports teacher at a college in the Chinese city of Tianjin, the same city in which he was born. After 12 years, Liddell opted to become an ordained minister and then continued his work spreading the word of God in the Xiaochang county as an evangelist and humanitarian.

While serving there, Liddell rescued two wounded Chinese soldiers, despite the significant risk involved. Other stories tell of Liddell refusing to travel with an armed guard when visiting sick and needy people because relying on a gun instead of God wasn’t his thing. Why was this all so risky? At this time, the Japanese were attacking China and Liddell ran the risk of being shot every time he walked out of the door. The situation was so dangerous that the British government advised him and other British citizens to leave the country. Liddell’s family left, but he stayed to work at a mission station setup to help the poor.

However, his luck eventually ran out and when Tianjin fell under Japanese control; Liddell was sent to an internment camp in Weihsien in March of 1943. Though his situation was certainly dire, his spirit certainly didn’t wane and while some people in the camp selfishly hoarded their supplies, Liddell spent his time teaching children and sharing what he had. When a few rich businessmen managed to convince the guards to smuggle them in extra rations, Liddell’s natural charisma was such that he was able to convince them to share the food with everyone, and he was the first port of call when any dispute in the camp needed to be settled.

He even reportedly finally took part in a sporting event on a Sunday. A fight broke out in game. To stop it, Liddell, who was well respected by all in the camp, stepped in and then after things settled down volunteered to referee the rest of the match. Given this wasn’t about his own glory, but rather about keeping the peace, it presumably didn’t conflict with his ideology.

If you’re not impressed yet with Liddell’s integrity. Here’s the part that really shows you the kind of man he was. While in the camp, Liddell was ravaged by malnourishment and ill health. (It was later found that he had a brain tumor, but he knew nothing of this.) Despite this, when Winston Churchill managed to secure Liddell’s freedom in a prisoner exchange, Liddell declined and instead offered his place to a pregnant woman who was also in the camp, saving not only her life but her unborn child as well. Besides his declining health, this must have been a particularly difficult decision given that he had a wife and three daughters he hadn’t seen in well over a year; one of them, Maureen, he never got a chance to know.

Much like most of his life’s work, he didn’t do this for any sort of fame or recognition. In fact, he didn’t even mention this fact to his family in subsequent letters. In his last letter to his wife as his health deteriorated, he simply mentioned that he thought he was perhaps overworked.

On the 21st of February 1945, just a few months before the camp was liberated, Liddell died.

Now, after reading about how Liddell spent over a decade in China helping others, some of the time voluntarily in a war-zone, and how he gave away his one chance at freedom for the life of a virtual stranger when he was in ill health and desperately in need of a doctor, perhaps the fact that he could move his legs slightly faster than other athletic humans for 400 metres isn’t the thing we should all be remembering him for. It’s true that athletic events have the power to inspire us and that can be very important; but in the end, it’s typically superficial. This is a rare case of an athlete doing something even more meaningful, and no less inspirational.

As Liddell said when asked about walking away from athletics at the peak of his career to become a missionary and humanitarian: “It’s natural for a chap to think over all that sometimes, but I’m glad I’m at the work I’m engaged in now. A fellow’s life counts for far more at this than the other.”

We’ll leave off this one with a quote about Liddell from Langdon Gilkey, a fellow survivor of the camp the two were prisoners in:

Often in an evening I would see him bent over a chessboard or a model boat, or directing some sort of square dance – absorbed, weary and interested, pouring all of himself into this effort to capture the imagination of these penned-up youths. He was overflowing with good humour and love for life, and with enthusiasm and charm. It is rare indeed that a person has the good fortune to meet a saint, but he came as close to it as anyone I have ever known.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- A 61 Year Old Potato Farmer Once Won One of the World’s Most Grueling Athletic Competitions

- The Mass Murdering Warlord Turned Christian Evangelist Who Was Known as General Butt Naked

- Why There Are Bibles in Hotel Rooms

- The First Woman To Officially Run in the Boston Marathon

- What Causes the Pain in Your Side You May Occasionally Feel While Running

Bonus Fact:

- About a year after his world record setting 400 metre time in the Olympics, Liddell managed to win the 100 metre (10 seconds), the 200 metre (22.2 seconds), and the 400 metre (47.7 seconds) in the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association meet in Glasgow, his last races in the UK before becoming a missionary, though he did occasionally compete in China when it was convenient given where he was working and as time permitted.

- Flying Scot Refuses To Run On Sunday

- Chariots of Fire’s Eric Liddell is Chinese ‘hero’

- Eric Liddell

- 50 stunning Olympic moments: No8 Eric Liddell’s 400 metres win, 1924

- Video of Eric Liddell Winning Gold at the 1924 Olympics

- Eric Liddell (1901-1945) Surrendered Olympian

- Recollections of Eric Liddell By Dr. Kenneth McAll

- Pray for China

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

he ran quite a bit slower than 10 seconds for 100metres – nevertheless, a great athlete, godly man. The discipline involved in one arena of life would have been a boon to the other

The brain tumor could be the direct cause of his saintly behaviour.

So his generosity and overzealous kindness to stranger may have been a neurological disorder forcing him to sacrifice himself for others.

It was by the power of the Holy Spirit within him!

Dear Adam,

You really have no understanding of saintliness. Kindness is not a pathological condition!

Your kidding of course. A brain tumor doesn’t make him a Christian as he professed. Read your Bible if you can find one. SMH

I often think about God and His purposes. My neighbor, a Christian of some note, passed away last Monday. He was afflicted with an aggressive brain tumor and in the course of one year I watched him decline and die.

There was never a hint of self-pity in him or in his family as they planned their last year together. They radiated a love for each other and a deeper devotion to God as they approached the end.

God chooses plans and directs our lives with great precision; his purposes are far beyond our comprehension and that is where faith enters and supplies the hope that Christians embody.

God took Eric Liddell home when his task was finished. I can only rejoice in his life and in Walt’s life because those lives show God’s presence in our midst.