The Quest for the Four Minute Mile

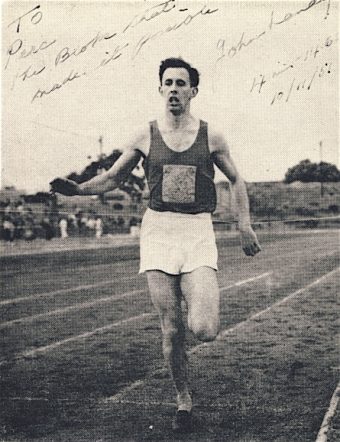

On May 6, 1954, just under one year after New Zealand climber Edmund Hillary and Nepalese mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first humans to reach the top of Mount Everest, another seemingly insurmountable barrier was crossed- a human being ran the mile in less than four minutes. The man who did it was 25-year-old British medical student Roger Bannister, finishing with a time of 3:59.4. This not only sent the cheering fans in Oxford’s Iffley Stadium into hysterics, but shook the track and field world.

On May 6, 1954, just under one year after New Zealand climber Edmund Hillary and Nepalese mountaineer Tenzing Norgay became the first humans to reach the top of Mount Everest, another seemingly insurmountable barrier was crossed- a human being ran the mile in less than four minutes. The man who did it was 25-year-old British medical student Roger Bannister, finishing with a time of 3:59.4. This not only sent the cheering fans in Oxford’s Iffley Stadium into hysterics, but shook the track and field world.

At the time, the previous record of 4:01.4, set by Sweden’s Gunder Haag, had stood for nine years despite a considerable number of attempts to break it. This ultimately resulted in somewhat outlandish speculation by various contemporary sports writers that finishing under four minutes in the mile was simply physiologically impossible for a human- a notion the runners themselves thought absurd. As one of Bannister’s chief competitors in the quest for the four minute mile, John Landy, noted, “It was simply a barrier in terms of conditioning by runners at that time, the track conditions, and the competition.” That said, he did note that, “The four-minute mile had become the Mount Everest of track and field.”

While the Olympic quest to go faster, higher and stronger has long driven athletes to do just that, the Olympics themselves have never been a place to break the four minute mile as this event goes by metric distances. (See: The Evolution of the Metre) The closest event in the Games, the 1500 meter, is only 93.3% of the full 1609.4 meter equivalent of a mile. However, it was the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki that Bannister and his two chief rivals, American Wes Santee and the aforementioned Australian John Landy, suffered defeats humiliating enough to seek redemption through chasing the mark.

Bannister was a man who took pride in his own training methods — with theories on everything from oxygen consumption to evenness of splits –as well as maintaining a balance between running and the rest of his life. However, Bannister was planning on dropping running after the 1952 Games to focus on his chosen career as a physician. But when he finished 4th in Helsinki, he invoked the wrath of the British press who scapegoated his independent-minded training ideas as the reason the Brits did so poorly in the track events. Feeling he had something to prove, the medical student changed his mind and doubled down on running.

Another runner at the 1952 Olympics, Australian John Landy, left the track in disappointment after failing to qualify for the finals. However, Landy left the meet with a dose of inspiration from the era’s dominant distance runner “the Czech Locomotive” Emil Zátopek. Zátopek won Gold at those Games in the 5,000 meter, 10,000 meter and the marathon (the latter being the first he’d ever competed in, entering on a whim at the last minute). One of Landy’s teammates ran three miles to the closed off Soviet Olympic village and slipped past the guards just to seek counsel with Zátopek.

Another runner at the 1952 Olympics, Australian John Landy, left the track in disappointment after failing to qualify for the finals. However, Landy left the meet with a dose of inspiration from the era’s dominant distance runner “the Czech Locomotive” Emil Zátopek. Zátopek won Gold at those Games in the 5,000 meter, 10,000 meter and the marathon (the latter being the first he’d ever competed in, entering on a whim at the last minute). One of Landy’s teammates ran three miles to the closed off Soviet Olympic village and slipped past the guards just to seek counsel with Zátopek.

Regaled with stories from his teammate, Landy joined the entourage of admirers that followed Zátopek around as he warmed up and pontificated about his running regimen. What he learned from Zátopek wasn’t running style and form, but that the key to success in running was rigorous year-round training to build up endurance. This is something that’s exceedingly obvious to anyone today, but at the time went very contrary to the popular idea that you should train as little as possible when not gearing up for a race, even taking many months off at times, thereby not putting too much stress on the body. Zátopek, on the other hand, advocated continual intense interval training and felt the more you stressed the body the better, so long as you let it heal up sufficiently between training sessions.

Using Zátopek’s training methods, within a few months of the 1952 Games, Landy managed the fastest mile time since Gunder Haag set the record at 4:01.4 in 1945. Landy’s new personal best was 4:02.1, cutting 9 seconds off his best time from before he changed his training routine. Shortly after this, on January 3, 1953, he managed a pace of under 4 minutes on the mile until the final 20 seconds, in which he ran out of gas, slowing considerably and finishing at 4:02.8.

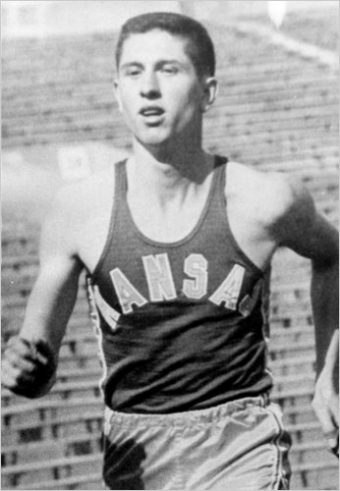

Wes Santee, a University of Kansas sophomore who had been breaking American records left and right, had an even bigger chip on his shoulder. The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) was the bane of his existence throughout his career, primarily concerning that he continually drew truly massive crowds at the races he competed in, but was not allowed to earn money from it. This was something the poor Kansas farm boy wasn’t shy about railing against, even publicly, making him many enemies within the AAU.

Wes Santee, a University of Kansas sophomore who had been breaking American records left and right, had an even bigger chip on his shoulder. The Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) was the bane of his existence throughout his career, primarily concerning that he continually drew truly massive crowds at the races he competed in, but was not allowed to earn money from it. This was something the poor Kansas farm boy wasn’t shy about railing against, even publicly, making him many enemies within the AAU.

In this first run-in with the AAU, however, the trouble was not about amateur athlete exploitation, but in the AAU denying him entry into his best race, the 1,500 meter, at the 1952 Olympic Games. Their reason? He had already qualified in the 5K for the Olympics and they didn’t think he could perform well in either if he competed in two events.

To keep him from running at the 1,500 meter Olympic trials, two AAU officials physically pulled him off the starting line mere moments before the race. Shortly before the Games, as something of a middle finger to the AAU, Santee raced the American 1,500 meter entrants, Bill Ashenfelter and Warren Druetzler, in a 3/4 mile (1207 meter) competition and effortlessly defeated them both.

At the Games themselves, Santee was alienated from the team over his conflict with the AAU and was given little support from them for the race. To make matters worse, his college coach had not been able to make the trip, leaving him on his own to vainly try to strategize a race where he didn’t really know much of anything about any of the other competitors. The result was one of his worst 5K times as an adult, ultimately finishing 13th at the Games. Track & Field News stated that Santee inexplicably ran the 5K at the Games “like a novice.” After the Olympics, Neal Bascomb noted in his book The Perfect Mile:

[Santee] wanted to prove what a big mistake it had been to prevent him from running in the 1,500 meter, and more important, he wanted to show how good he really was. He set his sights on a goal that had always been on the horizon for him: The four-minute mile.

Although Santee and Landy were not the first to break the four minute mile barrier, it was the relentless improvement of their personal bests that pushed Bannister and his support team to break the mark sooner than later out of fear that one of those two would conquer the “Mount Everest of track and field” first.

In the months leading up to the record breaking race, despite Santee competing exceptionally frequently compared to Landy and Bannister (sometimes even racing multiple times in a single day in various events and frequently racing several times a week), he had nonetheless reduced his personal best time in the mile to 4:02.4. At this point, he hoped to make his big push for the sub-four minute mile after the college season ended that year and he could properly rest for such a push.

As for Landy, he’d managed a personal best of 4:02.0 in the mile and several more times in the 4:02.X range in early 1954.

With Santee nearly getting their despite his rigorous race schedule and Landy coming so close so many times, Bannister, whose personal best at the time matched Landy’s 4:02.0, knew if he were to be first, he’d have to pass the mark soon.

Leading up to the day of the fateful race, Bannister took five days off of running, though did do some light hiking. When the run started, he later stated, “I can remember feeling so full of running that on the first lap I called out to Chris Brasher, ‘Faster!’ In fact he did 57 seconds. There was nothing wrong with the pace.”

After the second lap, Chris Chataway took over pacing from Brasher, and continued through about the half way point of the last lap. As Chataway tired and began to slow, Bannister “unlock[ed] my finishing burst” and sprinted past him to the finish line. “I leapt at the tape like a man taking his last spring to save himself from the chasm that threatens to engulf him,” then gasped for breath as he slowed. He later stated, “I felt like an exploded flashlight with no will to live.”

As the crowd and Bannister anxiously waited for his time to be read, the stadium announcer, Norris McWhirter, finally spoke, dragging the suspense out as long as possible,

Ladies and gentlemen, here is the result of event nine, the one mile: first, number forty one, R. G. Bannister, Amateur Athletic Association and formerly of Exeter and Merton Colleges, Oxford, with a time which is a new meeting and track record, and which—subject to ratification—will be a new English Native, British National, All-Comers, European, British Empire and World Record. The time was three…

The roar of the crowd drowned out the rest of the digits. His time was 3:59.4.

A mere month later, Wes Santee would break the world record in the 1,500 meter with a time of 3:42.8, then for good measure continued running in an attempt to become the second person to cross the four minute mile barrier.

He failed, with a time of 4:00.6.

Less than a year later, peaking at 4:00.5 for the mile and holding three of the five fastest mile times in the world at that point, he was temporarily banned by the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) for accepting money to race. According to the AAU, he had been given “at least $1,200” (about $10,000 today) to cover his expenses for travel, food and lodging in three races in May of 1955. At the time, the AAU only allowed the organizers of their races to give $15 per race to the athletes, despite crowds that sometimes swelled into the tens of thousands paying to watch Santee run.

Later, questions about Santee’s amateur status likewise saw him permanently banned from AAU events and international competition. Because there was no professional running organization at the time, after finishing up his tour with the Mariners shortly after being banned, where he at least could still compete in their running events, he never competed again, his personal best missing the four minute mile mark by a half a second.

Santee later bitterly noted of this, “The AAU says it is possible to get by on the expense allowances permitted by their rules. My answer to that is, ‘Yes, if you want to become an athletic bum.’”

He also mused about the fact that it was AAU officials who were the promoters who commonly offered extra money to the best runners to come race at their events, including stating that the then head of the AAU, Dan Ferris, had once paid him to race. He quipped of this, “I always questioned how they could be the ones giving me the money and on the other hand banning me for it.”

As for Landy, just over two weeks after Santee’s 4:00.6 failed attempt at a sub-4 minute mile, and 46 days after Bannister’s successful one, John Landy would not just cross the four minute mile barrier, but shatter Bannister’s fresh world record by 1.7 seconds, managing a time of 3:57.9 seconds (which was officially rounded by the IAAF to 3 min 58.0 seconds) on June 21, 1954.

As for Landy, just over two weeks after Santee’s 4:00.6 failed attempt at a sub-4 minute mile, and 46 days after Bannister’s successful one, John Landy would not just cross the four minute mile barrier, but shatter Bannister’s fresh world record by 1.7 seconds, managing a time of 3:57.9 seconds (which was officially rounded by the IAAF to 3 min 58.0 seconds) on June 21, 1954.

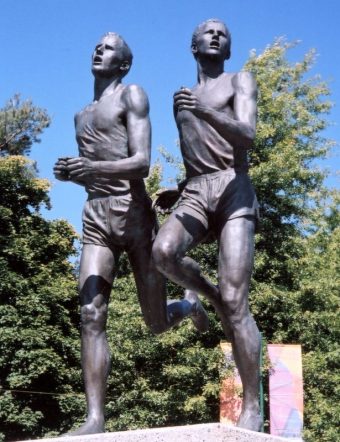

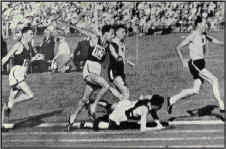

On August 7 of that same year, Landy and Bannister would go head to head at the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games in Vancouver, B.C. in one of the most anticipated races of the day. In it, for the first time in history, two competitors both managed a sub-four minute mile, with Landy finishing at 3:59.6 and Bannister at 3:58.8. Landy had led up to the last bend before he decided to turn and look over his left shoulder to see where Banister was- an opportunity Banister used to sneak past him on the other side.

Notably, about seven months later, Landy ran an incredible race of 4:02.0. Why is that impressive? Because it included him stopping completely mid-race after he accidentally spiked Ron Clarke on the arm when Clarke tripped and fell in front of him. Rather than continue running, Landy stopped to make sure Clarke was alright, helped him up and apologized for accidentally stepping on him with his spiked shoes.

Once back on his feet, Clarke urged Landy to continue the race, which he did. The total time Landy was standing still was about 7 seconds. He finished with the aforementioned time of 4:02.0, meaning he likely would have shattered his own world record of 3:58.0 had he not stopped. (This is not unlike that time an Olympic rower stopped to let some ducks swim by and still won the gold medal.)

Once back on his feet, Clarke urged Landy to continue the race, which he did. The total time Landy was standing still was about 7 seconds. He finished with the aforementioned time of 4:02.0, meaning he likely would have shattered his own world record of 3:58.0 had he not stopped. (This is not unlike that time an Olympic rower stopped to let some ducks swim by and still won the gold medal.)

After their respective racing careers were over, Bannister would be knighted and enjoyed a distinguished career as a neurologist, his research in the latter, according to him, being his proudest achievement in life, not the sub-four minute mile. Landy would pursue a successful career in business before becoming Governor of the State of Victoria in Australia. Santee would go on to own an insurance agency in Kansas, as well as give regular running clinics to high school and college athletes.

And if you’re wondering, today, the current mile record is 3:43.13, held by Morocco’s Hachim El Guerrouj, who set the record in 1999 and also holds seven of the ten fastest times for the mile in history. Since then, no one has come close to surpassing that mark. As for the so-called “metric mile” of 1500 meters, that record has stood at 3:26:00 since 1998, also held by Guerrouj, perhaps indicating that humans have actually come close to the fastest a human can run such a distance without the aid of performance enhancing drugs.

If you liked this article, you might also enjoy our new popular podcast, The BrainFood Show (iTunes, Spotify, Google Play Music, Feed), as well as:

- Late for the Olympics: The Amazing Story of Kipchoge Keino

- The First Woman To Officially Run in the Boston Marathon

- The Heroic Death of Chariots of Fire’s Eric Liddell

- The Amazing Jim Thorpe

- The Trials and Tribulations of 1904 Olympic Marathon Runners

Bonus Facts:

- For women, the current mile record is held by Russian Svetlana Masterkova, with a time of 4:12.56, set in August of 1996.

- One of Roger Bannister’s pacers, Christopher Brasher, later won a gold medal in the 3000 steeplechase at the 1956 Melbourne Olympics. He made headlines at the time for going on 19-hour celebration binge and showing up drunk at the press conference. He later founded the London Marathon.

- In 2006, University of Pittsburgh sophomore Sam Bair III ran 4:00.14 sparking the race to become the first sub-four minute miler whose father had also run sub-four (the barrier was broken two years later by Darren Brown).

- Wes Santee

- The Complete Book of Olympics

- The Perfect Mile

- The Four Minute Everest – The Story and Myth

- IAAF

- The Family Affair

- 4 Minute Mile Record

- Breaking 4- A Family Affair

- Edmund Hilary Mount Climber

- Olympic Motto

- John Landy

- Alan Webb

- List of People Who Have Broken the 4 Minute Mile

- London Gazette 1974

- Landy Bannister Statue

- Wes Santee Obituary

- Wes Santee

- Emil Zatopek

- John Landy

- Four Minute Mile

- Roger Banister

- Tenzing Norgay

- Edmund Hillary

- 1500 Meter World Record Progression

- Hicham El Guerrouj

- Mile Run World Record Progression

- Landy Image Source

- Wes Santee Obituary

| Share the Knowledge! |

|

“BRITISH climber Edmund Hillary”? He was a New Zealander! He’s even on our $5 note!

I thought it was only the Aussies who misappropriated our famous people. Next, you’ll be saying the All Blacks are a British Rugby team…

Good catch. The mix-up was because he was part of a British expedition when he made the successful ascent.

Hi Steve, I wrote the article and wanted to give a sincere thank you for reading